At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 76

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

Part III – Options for Europe

Chapter 23 Abandon the Euro Costs, threats and opportunities

[PREVIOUS MATERIAL HERE]

[BY WAY OF EXPLANATION – I AM WRITING SECTIONS OF THIS CHAPTER AS I GET INFORMATION SORTED IN A COHERENT WAY – IN THE FINAL DRAFT – THE SECTIONS MIGHT BE ARRANGED IN A DIFFERENT ORDER TO WHAT WILL APPEAR HERE OVER THE NEXT FEW DAYS. I WROTE MUCH MORE TODAY THAN APPEARS BELOW – BUT THE TEXT BELONGS IN SEVERAL SUB-SECTIONS AND SO I THOUGHT IT WOULD BE LESS DISJOINTED FOR THOSE THAT ENJOY FOLLOWING THE UNFOLDING STORY IF I JUST KEPT WHOLE SUB-SECTIONS TOGETHER.]

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

Does EMU exit mean EU expulsion?

As part of the threats to dissaude nations from considering abandoning the euro, it has been argued that any nation that desired to unilaterally exit the EMU would simultaneously have to also revoke its membership of the European Union. Given the transfers systems within the EU, a nation that receive net benefit might think twice before throwing the baby out with the bath water. Greece for example, received net benefits from the EU Budget equal to about 2.4 per cent of its Gross National Income in 2012. There is no doubt that a nation can freely exit any international treaty, whenever it chooses. Neil MacCormick (1999: 127) noted that ‘Sovereign power is that which is enjoyed, legally, by the holder of a constitutional power to make law, so long as the constitution places no restrictions on the exercise of that power …” The Treaty of Lisbon finally caught up with this obvious fact. The EMU nor the EU is a federal state! While the Treaty remained silent on the question of whether a nation could exit the EMU, the updated Treaty of the European Union added Article 50 says that “Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.” (European Commission, 2010: 43). There is a negotiated process listed under this article but if there is a failure to agree on terms, then the Treaties lapse after 2 years. Even the German Constitutional Court (BVerfG) has ruled on more than one occasion that (following Maastricht and Lisbon) that national law is sovereign. In its decision on whether the Lisbon Treaty was consistent with German Basic Law, the BVerfg reasserted its view that the EU Member States remain “Masters of the Treaties” (“Die Mitgliedstaaten blieben die ‘Herren der Verträge'” Bundesverfassungsgericht, 2009: Paragraph 150). It also concluded that any of the provisions of the European Treaties are considered to be “abgeleitete Grundordnung” (Paragraph 231), that is, a derived basic order (or law). They are derived from the constitutional law of the Member States, which remains surpreme. The Court also refused to recognise a situation where any Member State would allow the EU the freedom to create powers unilaterally (“Es untersagt die Übertragung der Kompetenz-Kompetenz” Paragraph 233).

Thus to eliminate all uncertainty in the discussion any Eurozone nation could unilaterally abandon the currency and exempt themselves from the provisions of the relevant Treaties any time they chose. It appears that a nation could not easily remain in the EU if it chose to reintroduce its own currency, notwithstanding the fact that there are non-Euro EU nations. This view was seemingly supported by a 2009 legal research paper published by the ECB (Athanassiou, 2009). But it is far from clear. Scott (2012: 6) raises the possibility that in the absence of anything explicit the principle of “the greater power includes the lesser” holds, which means that as Article 50 of the TEU allows a nation to leave the EU, it “necessarily creates a unilateral right to euro area-only withdrawal” (p.6).

Whether retaining EU membership is desirable is one matter. Nations such as Norway, Switzerland and Greenland do not seem to suffer from not being part of the Europa fold. Norway and Switzerland have never been in the EU, but Greenland was part of the European Economic Community (EEC) courtesy of Denmark’s membership. Once it attained self-rule in 1979, strong domestic opposition against the EEC (particularly over fishing rights) led to Greenland formally leaving the EEC in 1985. Nothing obviously bad has happened to them as a consequence. Interestingly, as part of its exit, Greenland negotiated the so-called ‘Greenland Treaty’, which allowed the nation to remain subject to some of the provisions of the European Treaties by dint of its status under the ‘Overseas Countries and Territories’ provision within the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Therefore it seems possible that any EU nation could abandon the euro unilaterally, negotiate to leave the EU, but on exit, sign a special ‘Italian Treaty’ (for example), which could, if there was the political will and the sense of mutual benefit, leave the nation within the EU scope. It can also be argued that Iceland, another non-EU nation, has recovered from its financial collapse much more quickly and robustly as a result of exercising its own sovereignty. It is highly unlikely that had it been part of the Eurozone, it would have navigated through the crisis as well as it did. There is every possibility that the Troika would have imposed draconian austerity on it, forced it to prop up the zombie banks and carry the resulting financial burden, and forced it to pay the spurious claims made by the British and Dutch governments for recompense for the losses their citizens incurred during the bank collapses.

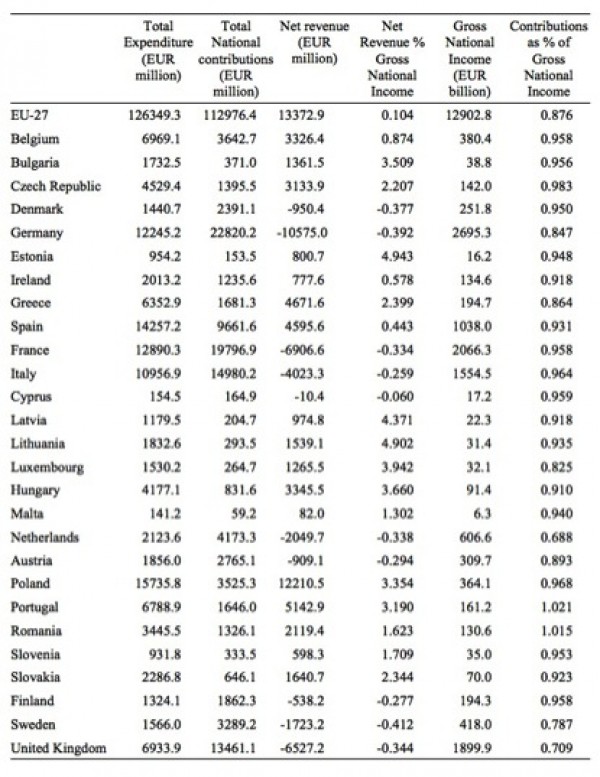

However, a nation such as Italy could show leadership in this uncertain world of Treaties and constitutional law. As a foundation member of the European Coal and Steel Community, which was established by the Treaty of Paris in 1951 as the start of the ‘European Project’, Italy has a status that Spain and Greece, for example do not enjoy. Remember that Helmut Kohl’s policy advisor, Joachim Bitterlich had indicated during the convergence years leading up to Stage III that Germany could not exclude Italy from the EMU despite it obviously being unqualified for membership on the basis of the stated criteria, because “We all shared a certain love for Italy” (Der Spiegel, 2012, Part 1). But sentiment is one thing. Italy has another qualification to lead the way out of this mess. Table 24.1 shows the financial report for the European Union Budget for 2012. The data shows the total funds (millions of euros) that a nation receives from the centre, its national contribution to the EU fiscal resources and the net funds it either receives (a +) or pays (a -) as well as the scale the contributions and net transfers in terms of the nation’s Gross National Income (GNI). It is clear that Italy is the fourth-largest net contributor to the EU budget and the fourth-largest economy. Neither can be ignored by the other EU nations in the same way they might brush of any claims by Greece for a ‘special’ Greece-Treaty.

Table 24.1 European Union Budget Summary, by nation, 2012

Source: European Commission, Financial report of financial year 2012, http://ec.europa.eu/budget/biblio/documents/2012/2012_en.cfm

Italy should abandon the euro and restore the lira and allow it to float in international currency markets. But it also should use its position in Europe to negotiate a Treaty change such that nations could remain in the EU while restoring their own currencies. This would establish symmetry in the status of all EU nations such that a nation that had entered the EMU could enjoy the same status as those that negotiated to remain outside of it (that is, the UK and Denmark).

[CONTINUE TOMORROW – OUTLINE THE LIKELY COSTS AND BENEFITS AND THE WAY IT COULD BE IMPLEMENTED TO MINIMISE THE FORMER AND MAXIMISE THE LATTER]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Athanassiou, P. (2009) ‘Withdrawal and Expulsion from the EU and EMU: Some Reflections’, Legal Working Paper Series, European Central Bank, No 10, December. www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/scplps/ecblwp10.pdf

Bundesverfassungsgericht (2009) ‘Entscheidungen: Lissabon-Urteil’, 2 BvE 2/08 vom 30.6.2009. http://www.bverfg.de/entscheidungen/es20090630_2bve000208.html

ECB (2014) ‘Capital Subscription’, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/orga/capital/html/index.en.html, Accessed May 1, 2014.

European Commission (2010) ‘Consolidated versions of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of

the European Union ‘, Official Journal of the European Union, C83, 30.3.10.

MacCormick, N. (1999) Questioning Sovereignty, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Policy Exchange (2012) ‘Wolfson Economics Prize 2012’. http://www.policyexchange.org.uk/component/zoo/item/wolfson-economics-prize-2012

Reuters (2005) ‘Italy minister says should study leaving euro-paper’, June 3, 2005.

Scheller, H.K. (2004) ‘The European Central Bank – History, Role and Functions’, European Central Bank, Franfurt. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ecbhistoryrolefunctions2004en.pdf

Thieffry, G. (2005) ‘The not so unthinkable – the break-up of the European Monetary Union’, International Financial Law Review, July. http://www.iflr.com/Article/1978253/Not-so-unthinkablethe-break-up-of-European-monetary-union.html

Voßkuhle, A. (2012) ‘Über die Demokratie in Europa’, Speech to Rhur Political Forum, Dortmund Concerthall, February 6, 2012 published in Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ), 13/2012, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 3-9.

Wetzel, D. (2001) A Duel of Giants: Bismarck, Napoleon III, and the Origins of the Franco-Prussian War, Madison, The University of Wisconsin Press.

Wolf, M. (2013) ‘Why the euro crisis is not yet over’, Financial Times, February 19, 2013. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/74acaf5c-79f2-11e2-9dad-00144feabdc0.html#axzz30L8DwwS0

Wolf, M. (2014) ‘Managing a Bad Monetary Marriage’, paper presented to iNET Conference, Toronto, Canada, April 2014.

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments