It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Buffer stocks and price stability – Part 4

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text during 2013 (to be ready in draft form for second semester teaching). Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

Progress Report

We are now in the process of final integration of all materials so far written. Not all of that material has appeared in these Friday pages. By the end of June we will have a first draft available and it will be trialled at two universities in second semester.

We will also be developing detailed databases and analytical exercises for the on-line support site from July to December 2013. The final publication is planned for later 2013. We hope to launch it at the – CofFEE Conference – in December 2013 in Newcastle, Australia.

Previous parts to this Chapter:

- Buffer stocks and price stability – Part 1

- Buffer stocks and price stability – Part 2

- Buffer stocks and price stability – Part 3

Chapter 13 – Buffer Stocks and Price Stability

[Continuing from Part 3]

Inflation control and the JG

While introducing a public sector job creation capacity to the economy, the JG is better thought of as a macroeconomic policy framework designed to ensure that full employment and price stability is maintained over the private sector economic cycle.

What are the mechanics of inflation control under a JG? In Chapter 12, we examined the way in which incompatible claims over the available real income could cause wage-price pressures to escalate into an inflationary episode as the claimants (labour and capital) attempted to defend their real income shares.

In an unemployment buffer stock system the approach to price control uses unemployment to discipline wage demands by workers and to soften the product market to discourage profit-margin push by firms as a means of curbing wage-price pressures and maintaining stable inflation.

We define the Buffer Employment Ratio (BER) as:

(13.1) BER = JGE/E

where JGE is total employment in the Job Guarantee buffer stock and E is total employment in the economy. The BER rises when the JG pool expands and falls when the JG pool contracts.

The JG approach stands in contradistinction to the NAIRU approach because instead of manipulating the employment rate by creating unemployment when wage-price pressures develope, the government manipulates the BER.

When the level of private sector activity and the distributional conflict is such that wage-price pressures forms as the precursor to an inflationary episode, the government manipulates fiscal and monetary policy settings (preferably fiscal policy) to reduce the level of private sector demand.

Labour is then transferred from the inflating private sector to the “fixed wage” JG sector and the BER rises. This will eventually ease the inflationary pressures arising from the wage-price conflict.

The can be no inflationary pressures arising directly from a policy where the Government offers a fixed wage to any labour that is unwanted by other employers.

The JG involves the Government buying labour off the bottom, in the sense that minimum wages are not in competition with the market-sector wage structure. By definition, the unemployed have no market price because there is no market demand for their services.

By not competing with the private market, the JG would avoid the inflationary tendencies of past Keynesian policies, which attempted to maintain full capacity utilisation by ‘hiring off the top’ (that is, making purchases at market prices and competing for resources with all other demand elements).

The BER conditions the overall rate of wage demands. When the BER is high, real wage demands will be correspondingly lower and the capacity of firms to push profit margins up is reduced.

So instead of a buffer stock of unemployed being used to discipline the distributional struggle, the JG policy achieves this via compositional shifts in employment – transfers in and out of the JG pool.

Importantly, the JG can also deal with a supply-shock (such as a rise in a key non-labour raw material) that generates incompatible claims on national income that ultimately cause inflation.

|

The NAIRU defines the unemployment buffer stock associated with stable inflation. In a JG setting, we define the Non-Accelerating Inflation Buffer Employment Ratio (NAIBER) as the BER that results in stable inflation via the redistribution of workers from the inflating private sector to the fixed price JG sector.

The NAIBER is a full employment steady state JG level, which is dependent on a range of factors including the historical path the economy thas taken. |

An aim of government is to minimise the NAIBER so that higher levels of non-JG employment can be sustained with stable inflation. Initiatives that may reduce the value of the NAIBER include public education to stimulate skill development and engender high productivity growth; institutionalised wage setting processes where productivity growth is shared equitably across all income claimants; restrictions on anti-competitive cartels that may add pressures for profit margin push.

However, while central banks and treasuries devote a lot of resources to trying to estimate the NAIRU, we consider it would not be worth trying to estimate or target a particular NAIBER. The point is that the aim of policy is to fully employ labour while maintaining price stability.

A plausible adjustment path

A plausible story to show the dynamics of a JG economy compared to a NAIRU economy would begin with an economy with two labour sub-markets: Sector A (primary) and Sector B (secondary) which broadly correspond to the dual labour market depictions we examined in Chapter 10.

Assume as before that firms set prices according to mark-ups on unit costs in each sector.

Wage setting in Sector A is contractual and responds in an inverse and lagged fashion to relative wage growth (Sector A/Sector B) and to the wait unemployment level (displaced Sector A workers who think they will be re-employed soon in Sector A).

So when the ratio of Sector A wages to Sector B falls, workers in Sector A will eventually seek to reinstate the past relativity, which reflects their sense of worth in the wage structure and their bargaining capacity as skilled workers. Increasing numbers of unemployed workers waiting for work in Sector A (but not taking Sector B jobs) also depresses wages growth in Sector A.

In a non-JG economy, a government stimulus increases output and employment in both sectors immediately. Wages are relatively flexible upwards in Sector B and respond immediately. The compression of the Sector A/Sector B wage relativity stimulates wage growth in Sector A after a time.

Wait unemployment falls due to the rising employment demand in Sector A but also rises due to the increased probability of getting a job in Sector A. That is, workers who had previously taken Sector B jobs in desperation or were classified as being outside the labour force may leave their Sector B jobs or re-enter the labour force in expectation of a prospect of a better paying Sector A job, which is more in line with their skill levels. The net effect of these two movements is unclear at the conceptual level.

The total unemployment rate falls after participation effects are absorbed. The wage growth in both sectors may force firms to increase prices, although this will be attenuated somewhat by rising productivity as utilisation increases.

A combination of wage-wage and wage-price mechanisms in a soft product market can then drive inflation. These are the type of adjustments that are described in a Phillips curve economy.

To stop inflation, the government has to repress demand. The higher unemployment brings the real income expectations of workers and firms into line with the available real income and the inflation stabilises – a typical NAIRU story.

Now consider what would be different in a JG economy. Introducing the JG policy into the depressed economy puts pressure on Sector B employers to restructure their jobs in order to maintain a workforce.

For given productivity levels, the JG wage constitutes a floor in the economy’s cost structure. The dynamics of this economy change significantly.

The elimination of all but wait unemployment in Sector A and frictional unemployment does not distort the relative wage structure so that the wage-wage pressures arising from variations in the Sector A/Sector B relativity that were prominent previously are now reduced.

The wages of JG workers (and hence their spending) represents a modest increment to nominal demand given that the state is typically supporting them on unemployment benefits. It is possible that the rising aggregate demand softens the product market, and demand for labour rises in Sector A.

But there are no new problems faced by employers who wish to hire labour to meet the higher sales levels in this environment. They must pay the going rate, which is still preferable, to appropriately skilled workers, than the JG wage level. The rising aggregate demand per se does not invoke inflationary pressures if firms increase capacity utilisation to meet the higher sales volumes.

With respect to the behaviour of workers in Sector A, one might think that the provision of the JG will lead to workers quitting bad private employers. It is clear that with a JG, wage bargaining is freed from the general threat of unemployment.

However, it is unclear whether this will lead to higher wage demands than otherwise. In professional occupational markets, some wait unemployment will remain. Skilled workers who are laid off are likely to receive payouts that forestall their need to get immediate work.

They have a disincentive to immediately take a JG job, which is a low-wage and possibly stigmatised option. Wait unemployment disciplines wage demands in Sector A. However, demand pressures may eventually exhaust this stock, and wage-price pressures may develop.

A crucial point is that the JG does not rely on the government spending at market prices which then exploits the expenditure multiplier to achieve full employment as is characteristic of traditional Keynesian pump-priming. In this sense, traditional Keynesian remedies fail to provide an integrated full employment-price anchor policy framework.

From the above analysis it is clear that the introduction of a JG eliminates the traditional Phillips curve trade-off.

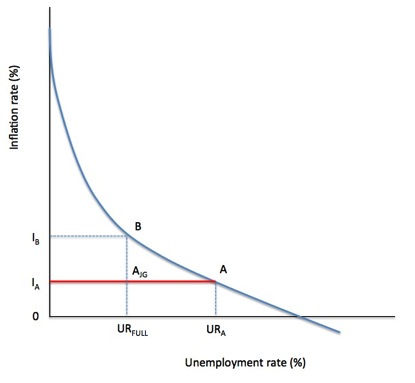

Consider Figure 13.1. In a Phillips curve world, imagine that the unemployment rate was currently at at URA and the inflation rate was IA.

The full employment unemployment rate is URFULL, which denotes frictional unemployment.

The government is under pressure to reduce the excessive unemployment and if it increased aggregate demand the wage-wage and wage-price pressures would drive the inflation rate up to IB although it could move along the Phillips curve from Point A to Point B and achieve full employment.

However, there is no guarantee that the inflation rate would remain stable at IB. Certainly, the NAIRU model would predict that bargaining agents would incorporate the new higher inflation rate into their expectations and the Phillips curve would start moving out. Whether that happens is not relevant here and we considered those issues in Chapter 12.

Figure 13.1 The Job Guarantee and the Phillips Curve

If the government initially responded to the excessive unemployment at Point A by introducing a Job Guarantee it could absorb workers in jobs commensurate with the difference between URA and URFULL, although in reality as the more work was available workers from outside the labour force (the hidden unemployed) would also take JG jobs in preference to remain without income.

But whatever the quantum of workers that would initially be absorbed in the JG pool, the economy would move from A to AJG rather than from A to B.

In other words, the introduction of the JG eliminates the Phillips curve. The macroeconomic opportunities facing the government are not dictated by a perceived unemployment and inflation trade-off and any fear that that trade-off might be unstable (as in a NAIRU world).

Rather full employment and price stability go hand in hand.

Conclusion

Next week I will finish this Chapter off.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I didn’t get the “Sector A & B” bit. If anyone else did, can they put it in their own words?

Hi Ralph,

Sector A and Sector B are referring to a stylized labour market model that Bill uses in Chapter 10. These are “dual” or “sub” labour markets.

Market B refers to lower paid, lower skilled jobs in which workers are threatened (and their wages disciplined) by the involuntarily unemployed who are actively attempting to enter the labour market. Without further training, education or workplace upskilling the workers in this market do compete with workers in Market A for jobs.

Market A covers higher paid, higher skilled jobs which have a skill/experience barrier to entry (think in-demand tradesman, senior management, lawyer, doctor, financial consultant). The workers in this market wish to maintain a relative wage difference with those Market B based on their perceived worth, which can be a cause of Wage-Wage and then Wage-Price inflation. Wages are disciplined in this Market by stock of “wait unemployed” who are competing for their jobs. The wait unemployed are Market A participants who have recently been displaced, but can afford to wait comfortably for a while due to the payouts from their displacement or due to the high levels of savings they have to draw from. Depending on economic conditions (how their industry has been affected by the business cycle) these people won’t even take a look into Labour Market B and will wait comfortably until they secure another Labour Market A which fits their skills/experience and perceived rate of worth. This competition helps tighten the wage pressure in this sector.

Hopefully Bills blog post will now make more sense to you, and you can offer criticism.

One point of criticism I have is that I do not think it is fair to state that under a JG the Philips Curve would be completely flat, which is what Bill has depicted here.

Firstly, don’t JG programs still compete in the product market for capital goods required for the setup or expansion of those programs? Lets say that pool of JG workers increases as a result of government fiscal contraction; the government would have to calculate its fiscal contraction to include demand pull effects of its outlays on JG capital goods.

Secondly, the goods and services produced by JG workers like other public sector output is “provided” rather than sold. That means the usage of the public goods and services provided does not reduce the aggregate demand in the private sector, included the increased demand from the JG wages. This is potentially inflationary! That said I see how this works as a form of automatic-stabilizer, as the extra demand from the JG wages would grow during a recession and fall during a boom. If higher accelerating inflation were to rear its head the government can still use its fiscal and monitory tool kits to drain private sector demand, reducing wage-wage and wage-price inflationary pressures as the JG Pool of workers discipline wages. I would argued that JG workers would be more effective at disciplining wages than the unemployed, but I can see reasonable objections.

As you’ve noted before, the government already pays the unemployed, who are are not producing sell-able output and this would just be a nominal increase in payments. In addition the JG programs have the potential to increase productivity due to better public infrastructure, lower crime rates and a labour market with less skill-atrophy and deterioration. I would appreciate more attention from Bill on these issues.

“Firstly, don’t JG programs still compete in the product market for capital goods required for the setup or expansion of those programs? ”

For setup, yes and that has to be taxed out if the program is setup when the private sector is in a boom. Although I would consider that an unlikely point at which JG is introduced.

However as the economy moves into a slump the private sector is reducing its demand for capital goods some of which the JG then uses for expansion. As the economy recovers and the JG shrinks demand for capital goods reduces and they are returned to the private market. So I would suggest that JG counterstabilises the capital goods market as well.

It has to be the case for effective inflation control that JG workers are organised in such a way that their output that crowds out the private sector. It has to be ‘nice to haves’ – preferably targeted at producing common goods and services that others can exploit to create new businesses. Hence the prevalence of ‘social value’ activities in the JG list – including reducing the negative cost shocks of bad health and bad behaviour.

Exactly how far towards ‘work’ = ‘anything you fancy doing’ the JG can go I think depends upon the social maturity of the society – in terms of how much reciprocation the society demands. But the more that it can move towards the ‘anything you fancy’ ideal, the less management overhead the JG requires and more of that is ‘privatised’ as the private sector has to improve its job offers and conditions to attract labour.

Our Labour Party here in the UK has gone for a ‘compulsory job guarantee for the long-term unemployed with the private sector’. So it’s clear that they believe that the maturity of the UK society is fairly low, that social projects are not perceived as having that much value and that the existing large incumbents in the private sector have to be permanently propped up British Leyland style with cheap state subsidised workfare labour – rather than being forced to compete for staff with improved wages and working conditions.

There is a way to go to win the argument that private sector companies have to compete for labour if they are to value it properly and learn to use it sparingly.

the struggle between wages and profit is not primarily an inflationary struggle

but a struggle for the share of real wealth

and the struggle for claims on the share of real wealth is increasingly a struggle amongst wage claims

in reality increasing disparity of wages is not a struggle at all but an exercise in power by those

setting the income rates

whilst a JG I would be a great improvement over current macroeconomic strategies of governments

it would not decisively win the struggle for equity of wealth and power

or rationalize economic production for the public purpose

once we except the notion that government has unlimited spending power in its own currency

its ambitions should rise above full employment by employing off the bottom

in the pursuit of public purpose it can employ more of bottom middle and top

I do not consider government buying all that is available in its own currency

best serves the public purpose .

what about that battle against inflation?

I do not see hyperinflation ready to pounce

as bill has explained its historical appearances are production shocks

the poor want to save as much as the better off

macroeconomic management should seek to maximize sustainable production levels

greater equity in government and private sectors can deliver necessary demand

to maximize such production

decent minimum income for all supported by direct delivery of universal government fiat

government direction of resources to historical sources of inflation (with sustainable criteria)

eg energy and housing

if necessary targeted price controls or subsidy or rationing

and above all an introduction of a maximum wage to rationalize the struggle between

competing income claims can all be utilized for governments to tackle both inflationary

problems and unfair and wasteful levels of inequity

I suppose at heart my problem with MMT is once I have excepted its analysis

of our monetary system it’s prescriptions seem unambitious

Andrew,

“the government would have to calculate its fiscal contraction to include demand pull effects of its outlays on JG capital goods.”

You’ve answered your own question. The fiscal adjustment would need to be larger to compensate, and as Bill has suggested in previous blogs, this may mean that an employed-buffer-stock would need to be somewhat larger than an equivalent unemployed-buffer-stock.

Kind Regards

Democratizing the workplace might be an alternative approach towards implementing a JG from the bottom up. But that would challenge the sanctity of private property. By comparison, implementing a JG as a result of an academic or technical consensus leaves the general population uninformed with regard to economic policy.