"Fiscal support can manage the direct economic fallout from extreme weather events." That quote came…

Terrestrial water storage capacity is declining fast and is hardly getting any attention

I read some disturbing research over the weekend about the rapidly declining terrestrial water storage (TWS) that is now becoming a global issue with drying regions linking up to form mega-drying areas that will be nearly impossible to reverse. While global warming gets a lot of attention in the media the surface water issue is not very well understood by the population, although it augurs devastation. I am working on a project at present that is focusing on new land use forms for the production of food and construction materials. The TWS problem is a central consideration in that it is being driven by poor land management and hopelessly inefficient and damaging agricultural practices, particularly those involved in producing animal protein. There are solutions but tell the next Greenie you meet tucking into some meat product that they have to stop eating that form of protein and see the reaction. That will tell you about how difficult it will be for societies to adapt and change.

As I flew into Melbourne today from the North, the flight goes over – Lake Eildon – which is about 150 kms north east of Melbourne.

It supplies “about 60% of the water used in the Goulburn-Murray Irrigation District” which is a major fruit and vegetable growing district in Victoria, Australia.

I am normally deep into some book at this stage of the flight so it was by perchance that I looked out the window just at the moment we passed over the Lake.

Even though I fly this route almost every week I was shocked to see how low the water level is at present – about 58.6 per cent as at September 14, 2025.

I took this photo from the plane.

If you visit this – Google Maps – page you will see what it looks like when there is more water.

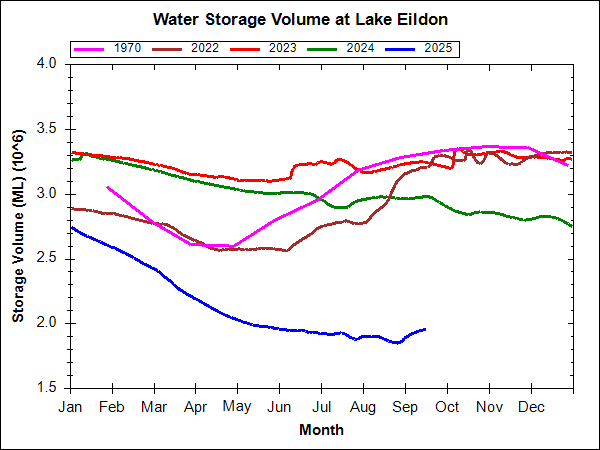

This graph compares the water storage volume in the Lake over several years.

This year is looking very bad by comparison.

And it was rather a clustering of similar disturbing information this weekend because on Sunday I read this ABS news article (September 14, 2025)- Perth had its wettest winter in 30 years. Why aren’t its dams full? – and late last week, I read this scientific research report from the Science Advances journal – Unprecedented continental drying, shrinking freshwater availability, and increasing land contributions to sea level rise (published July 25, 2025) which seemed to focus on a similar theme that is not very well highlighted in all the discussions about global warming.

The ABC news report noted that:

Despite 2025 being the city’s wettest winter since — with nearly as much rain — the Mundaring weir on the outskirts of Western Australia’s capital is barely half full, as are many across the city.

This dam supply much of the drinking water to the capital of Western Australia, Perth.

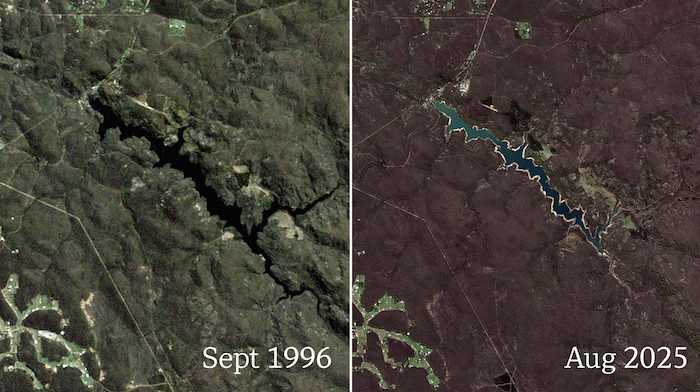

This pictorial comparison of Mundaring Weir (on the West coast) over time from NASA’s Harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 service is similar to what I saw over Lake Eildon (which is on the East coast) staring out the window and comparing today with the Google Maps image the link above takes to you.

Note that the Winter rain in 1996 and 2025 around the Lake Mundaring district was “almost identical”, which led the journalist to ask “where has all the water gone?”

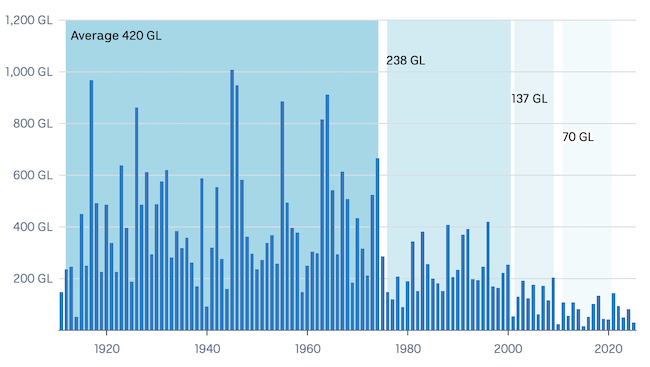

The ABC article shows how in this “corner of the planet” the “climate … has changed significantly” and provides a series of graphs to demonstrate the point.

Two salient facts are that:

1. Rainfall is now lower in this area – “WA’s South West, where Perth lies, is drying out at a globally significant rate — having faced a 15-20 per cent reduction in its rainfall since the 1970s.”

2. Summers are becoming much hotter.

And the run-off of the reduced rainfall that goes into the water storage systems that provide our drinking water – so-called ‘streamflow’ – has fallen by:

… a whopping 80 per cent over the past 50 years.

This graph demonstrates the problem.

The increased temperatures and duration of the hot periods have also mean that the “catchments are like a big sponge” osaksing up the rain before it can run off into the dams.

Evaporation rates are also rising.

On top of that is population growth – increasing the demand for the water resources – and it is no surprise that Perth’s groundwater levels have “fallen by up to 10 metres”.

Now, we could dismiss this as a local regional problem for one corner of Australia.

The problem is that:

Streamflow has declined across the majority of southern Australia, and globally, regions like Iran, South Africa, California, and south-west Europe are facing similar challenges …

Currently, 25 countries are experiencing extreme water stress, which is the ratio of water demand to renewable supply.

The worst hit are the nations with “a Mediterranean climate”.

So we need some hardcore scientific research to tap into to learn more and it was a coincidence that on Friday I read this article in the established Science Advances journal – Unprecedented continental drying, shrinking freshwater availability, and increasing land contributions to sea level rise (published July 25, 2025).

Science Advances “is the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) open access multidisciplinary journal, publishing impactful research papers and reviews in any area of science, in both disciplinary-specific and broad, interdisciplinary areas”.

I expect it to come under attack from the crazy Right including the President any time now because it provides solid scientific knowledge to the broader community.

Anyway, the article cited above is a shocking statement of how far we are down the road to desertification and food chaos.

The authors are from a range of academic and scientific institutions spread across the globe.

They provide a recent assessment of the state of “Changes in terrestrial water storage (TWS)” which:

… are a critical indicator of freshwater availability.

Over the last quarter of a century or so, they find that “continents have undergone unprecedented TWS loss” which has created:

“mega-drying” regions across the Northern Hemisphere.

This loss of TWS (“all of the ice, snow, surface water, canopy water, soil moisture, and groundwater stored on land”) is just one of the indicators of significant and damaging climate change.

Other indicators include:

1. “global temperatures continue to reach record heights”.

2. “the planet is experiencing increasing extremes of flooding and drought”.

3. “widespread glacial and ice sheet melt and sea level rise”.

4. “greater risk of wildfire … and biodiversity loss”.

The research found that:

1. “the continents (all land excluding Greenland and Antarctica) have undergone unprecedented rates of drying and that the continental areas experiencing drying are increasing by about twice the size of the State of California each year.”

2. “while most of the world’s dry areas continue to get drier and its wet areas continue to get wetter, dry areas are drying at a faster rate than wet areas are wetting.”

3. “the area experiencing drying has increased, while the area experiencing wetting has decreased.”

4. “A critical, major development has been the interconnection of several regional drying patterns and previously identified hot spots for TWS loss to form four continental-scale mega-drying regions, all located in the Northern Hemisphere.”

Many of these regions are major food production areas.

The implications of this loss of TWS and the connecting up of drying regions in these maga-drying regions is not often mentioned in the mainstream media.

The authors don’t mince words:

The implications of continental drying for freshwater availability are potentially staggering. Nearly 6 billion people, roughly 75% of world’s population in 2020, live in the 101 countries that have been losing freshwater over the past 22 years.

The research suggests that:

Key contributors to the expansion of drying regions, declining TWS, and shrinking freshwater supply include melting GICs, the increasing severity of drought, the decreasing surface water availability, and groundwater depletion and all are continuing.

GICs are glaciers and ice caps.

The drying does not appear to be ephemeral – the authors say that it is “robust” showing “little sensitivity to a lengthening” data time frame.

It appears that 2014 marked a turning point with “the dry and wet extremes” changing location and that:

… it is clear that increasing extremes of drought, in both areas, location and duration, are driving the growth of previously identified hot spots or drying regions, into interconnected, continental-scale mega-drying regions, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere.

Why has it been happening?

The authors find that “overpumping groundwater is the largest contributor to rates of TWS decline in drying regions, significantly amplifying the impacts of increasing temperature, aridification, and extreme drought events” – that is, poor water management and poor farming practices, which not only impacts on yield but threatens the overall food security.

The current generations are depleting TWS because there is no cost to future generations taken into account when setting the current price of water.

Further excessive clearing for animal protein production is massively destructive and unsustainable.

Humanity will not be able to continue consuming meat-based protein for much longer and should stop now.

The problems that are arising from the loss of TWS are global and widespread.

Starvation in Africa.

Shipping disruptions in the Panama Canal.

Global sugar prices soaring.

Olive farms in Spain depleted and driving up prices.

Soon enough we will see the tensions that arise when the growing number of environmental refugees seek new home in which to survive.

I am guessing the powerful nations will turn a blind eye to that problem in the same way that global leaders are ignoring the massive slaughter and genocide going on daily in the Gaza Strip, which is km by km being razed to the ground by private contractors who follow in the wake of the bommbings and killing.

Humanity has a way of ignoring history and anything that doesn’t immediately impact.

The problem is that we might be able to look the other way and watch episodes of ‘Big Brother’ just a few kms from where young children are being blown to smithereens by IDF armaments, but the impacts of the climate shock is starting to affect all of us.

On the IDF behaviour – this UK Guardian article is pretty depressing (September 14, 2025) – How to burst the Israeli bubble.

Conclusion

There are immediate solutions to this problem.

Less irrigation, abandon consumption of meat products, build better energy efficient houses to reduce the heating stress in colder climates, and more.

I predict most people will wait for the catastrophe before any significant change occurs.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Luke Kemp points out that the social and environmental costs of crucial resources like water and energy, as ‘externalities’, aren’t included in pricing, and as such, pricing then tends to select for environmentally and socially destructive types of technology and economic growth.

AI requires major increases in both energy and water resources.

I strongly question the hype and rationale for the development of AI technology on a number of levels, but the bottom line is that it is going to contribute massively to resource pressures just at a time when both energy and water resource management is needed on a co-ordinated planetary level.

There are two current global war zones where water resources underpin the military actions.

Firstly, the Levant is under huge water resource pressures, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict epitomises the problems. Israel has total control of all Palestinian resources, including hydrological, and already protects Israeli water resource utilisation at Palestinian expense in the West Bank.

The ill considered IDF plan to flood all Gazan tunnels with sea water was thankfully avoided, but that perverse logic was probably only circumvented because it would have destroyed the Gazan aquifers for any future Israeli settlements as well as for Palestinians. It is a mess.

Russia and the Ukraine combined account for over 5x Australian wheat exports, and also more than the USA and Canada aggregated.

Control of this market is 25%+ of global wheat exports.

It is probably more important than the capture of the residual fossil fuel resources in the Donbas as a significant resource and carries immense geo-political leverage.

Whether this is as much as Russian oil and gas markets is debatable.

The Chernozem soil areas of the European Steppes are globally important as bread baskets but, like the American prairies, are low rainfall areas, mostly under 400mm pa and are already drought susceptible, as in the 2010 drought.

Both Steppes and Prairies are vulnerable to climate change as water resources on both continents are actually fragile.

All these natural grasslands globally are delicate ecosystems.

Increased evapotranspiration is an obvious impact of rising temperatures, especially in seasonal maxima in continental climates.

Disruption of global wheat markets is an inevitability in the next few decades of climate change and it is highly likely adverse impacts will be amplified in areas under existing hydrological pressures.

Ukraine lost 10% of its surface water storage in the Kakhova dam destruction alone.

All the major Ukrainian river basins are crucial for irrigation.

Control of Ukraine’s hydrological resources is not a trivial matter.

Then we have the Pripet Marshes… located between Ukraine/Belarus/Poland and Russia, it is a crucial global wetland and hydrological buffer.

Another key geopolitical hydrological conflict zone involves two nuclear powers, already with delicate diplomatic relationships.

There are 275-325 million people living in the Indus basin.

India is already using its water resource controls in the Indus basin against Pakistan, and climate change impacts here are exacerbating every year with changes in the Himalayan glacial melt regime.

I’m afraid I don’t think there are actually any easy solutions to these problems.

The IPCC predicted that there would be increased resource disputes and geo-political conflicts as a result of climate change.

But here we are..

I can’t quite agree with everything you say in this post, Bill. I consider all humans to be natural-born omnivores and vegetarianism to be a lifestyle and/or a conscious ‘non-exploitation of animals’ choice. I eat some meat – not very much – and consider the resources used to provide meat, including water, to be a better use of resources than their allocation to provide trivial and luxury goods.

What matters most is that the rate at which we collectively use resources and generate waste – the throughput required to produce goods – is kept within the ecosphere’s regenerative and waste assimilative capacities. At the global level, the rate of throughput – the global Ecological Footprint – is exceeding global Biocapacity by close to 80%. This corresponds with other work revealing that humankind has transgressed six out of nine Planetary Boundaries, of which freshwater use is one of the six. You are therefore correct to point out the significance and urgency of the water crisis.

What we do with a sustainable rate of water use, if we could limit ourselves to a sustainable rate, is a distributional and allocative issue. Distribution matters more. Hence, it is important that every human gets at least a minimum cut of the sustainable water use rate, a lot of it embodied in the goods we consume. If that’s not possible (i.e., if the sustainable quantity divided by 8+ billion people is below the minimum required), we are in deep trouble, as we may well be (I haven’t seen a study on this, although one may exist).

The allocation of the sustainable rate of water use depends not just on the per litre cost of water use, but on the per litre benefits. As with anything, allocating scarce resources to produce useless widgets because the throughput-intensity of widget production is less than the throughput-intensity of useful gadget production (lower per unit cost), can be less than desirable. A million useless widgets produced from a given quantity of resources can be less desirable than 100,000 useful gadgets produced from the same quantity of resources. Vegetarian food is not useless, and I like vegetables more than I like meat. But I like meat more than I like to consume trivial stuff, and largely because I don’t believe in consuming lots of all stuff. It isn’t necessary, and it doesn’t add to human wellbeing.

I’d consider excluding meat altogether from my diet if it could be shown that we have reached the point where it is necessary to ensure everyone gets a minimum necessary cut of a sustainable quantity of water use. I don’t think (don’t know) if we are quite there yet, although it highlights how much an excessive population of humans is affecting our choices and our quality of life. I’d like to see meat being provided using better methods and always choose ‘free range’ options, although I don’t know the source of any meat I eat at a cafe/restaurant. I usually eat fish, if it’s not a vegetarian option, which I often choose. If we are going to consume meat, we should also eat more of our native animals, since they are better suited to the natural environment. I don’t think sheep and cattle are on the endangered species register.

It is more annoying/concerning to me that humankind is exceeding the sustainable rate of use of most types of resources because there are too many of us (and consequently there will be fewer humans who get to live in the long-run) and, more particularly, because per capita rates of resource use, especially in wealthy nations, is much higher than is needed to live a good and meaningful life.

Dear Philip Lawn (at 2025/09/16 at 10:29 am)

Thanks for your comment.

Of course, a lot of people with green sentiments tell me that “I eat some meat”, with the implication that some is moderation and so that is okay even though a lot is not.

The problem is that the way agriculture and fishing industries have evolved is that the techniques are not “some” but a “lot” and they are unsustainable.

So it doesn’t matter if a single individual eats “some”, that person is part of the total that supports the profitability of the sector, which cannot continue if we are to save ourselves from planet eradication.

best wishes

bill

I find it all rather hypocritical given we can’t participate / function in the modern world without destroying it.

Should we ban all air travel ? Should we ban the internet ? Should we cull the human race down to a more sustainable level ? Should we end capitalism… and so on.

Thanks for your reply, Bill.

I recall learning that the Murray-Darling Basin was dependent on irrigation 60 years ago in schools Geography lessons, and that much of Australia’s human colonisation was in areas with water resource pressures and issues.

We even drew cross sections of the distinct Great Artesian basin, though I suppose many of those areas now suffer from salination and mining generated problems.

That climate change is going to adversely affect commercial agriculture in the Murray Darling basin now is pretty much nailed on, for the next few decades.

What a threshold for collapse might be is open to debate.

Yet, the same resource over consumption issues apply to all of us, and equally to those with a predominantly vegetarian diet.

Meat eaters simply shifting to vegetarianism is not going to resolve the problems created by over irrigation and other pressures during the current climate shifts.

Industrial arable has higher energy inputs with inorganic nitrogen inputs across the board, and is highly mechanised in the world’s main cereal and soya producing areas, as well as in intensive horticulture. Soil conservation is a perennial problem in industrial arable areas – the UK fens, which I studied as an undergrad, having long been a classic example of unsustainability.

The Murray-Darling basin grows 95% Australia’s rice crop, 73% cotton, 75% grapes, 46% fruit and nuts and produces 36% of Australia’s dairying output.

The wider matter is that roughly 60% of global farmland is unsuitable for arable, down to soils/slopes/climate limitations. There are even still some 275m people across the planet who are dependent on transhumance.

Of the current 30%+ global arable farmed area, it is true that 50%+ of some cereal and soya output is used as animal feed in intensive feedlot industrial systems and that has to be the crucial target area for emissions and energy reduction.

Incidentally, the claimed gross figures for methane emissions from livestock don’t distinguish between types of ruminant diet – with extensive grazing having significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions than US style feedlots, just as UPFs are pretty bad for humans.

It is intensive industrial animal rearing systems that skew the aggregate data and which are the real causes of food production problems, not traditional mixed 3 and 4 field rotations which have mixed arable and grazing outputs.

The most productive and resource efficient agriculture seems to me to be on small holdings – with 40% of Russian food production being on urban dacha farms. Chinese quasi subsistence small plots (under 1ha) have long supported that nation’s billion plus population.

In India farm size is even smaller, and seems to be shrinking from fragmentation pressures.

I’d certainly question the oft cited conventional wisdom here that larger holdings are automatically more productive. I’d guess that much of this might be down to the lobbying powers of the multinational industrial agri-corporations.

Appalling food waste figures – 38% in the USA (other post industrial societies like the UK are equally dire) are as much, if not more of a problem than folks’ dietary balance.

That seems to be to be mostly down to the oligarchy of food retailers – a structural problem across the global economy.

Then, the damage being done by industrial fishing globally is absolutely phenomenal – again scale, unsustainability and lack of responsibility, are the problems.

The tragedy of the commons is writ large here.

It is only 35 years or so since cod almost totally disappeared from the incredibly productive Grand Banks fishery, yet there are local lobby groups wanting to restart commercial fisheries with stocks barely 10% recovered. Einstein’s supposed definition of madness applies.

I have to disagree with the proposition that all, or even most, of what we need to do in terms of feeding the global population sustainably is just to eat very little or no meat and that will sort out agricultural emissions and water resource issues.

I feel that, despite its evident partial truth, this grossly oversimplifies a much more complex set of land use and socio-economic issues.

I’ll declare that my own background as a farm-boy, with direct experience in farming, fisheries, and arboriculture, and as a social and environmental geographer, has certainly influenced my views, but then the vegan geographers working for ‘Our World In Data’ in Oxford, have also been influenced by their personal positions.

We have been enjoying a very sunny and warm summer in southeastern Ontario Canada in 2025, and of course it’s dry as a result.

It’s become apparent that climate change seems to mean we have torrential rains for short periods, in summer, and long periods were we have nothing but grey skies and precipitation of one kind or the other outside the growing season when it is not possible to grow fruit or vegetables. That is most of the year.

It’s impossible to live on a vegetarian diet here since produce from points south have very short shelf life by the time they arrive here.

There are a few things that can be successfully grown indoors year round.

Without animal protein, which is available year round since we can store things like hay for feed in winter, we would not be able to come close to having anything like a healthy diet over winter.

Looking around, the farms here do seem to be getting enough hay for feed. Grasses are quite hardy and grass fed animals are good sources of protein, healthy types of fat for energy, and when the soils are maintained by good farming practices we get all of the essential minerals from meat as well.

As implied there are good farming practices which conserve resources minimize the need for chemicals etc and there are poor farming practices which do not.

Humans can derive energy two ways. One is to eat carbohydrates and the other is to consume fat.

It isn’t practical for health reasons to consume these things together because while humans are dual fuel animals, it appears we adapted to the presence of one or the other rather than both at the same time.

There is a pandemic of type 2 diabetes in North America resulting from a metabolic disorder called insulin resistance, caused by trying to mix carbohydrates and fat in the diet. A mixed diet of that type gradually sabotage efforts to maintain a healthy body because carbohydrates are instantly cleaved into sugars as soon as they enter the body, raising blood sugar, which then results in secretion of insulin the fat storage hormone. The low levels of satiety generated by these mixtures of fat and carbs result in frequent eating because hunger follows the blood glucose. Only fat provides energy without this effect.

Perhaps we’ve had it because of this decline in terrestrial water but for the reasons given here, among others, reliance on plant based food is not feasible here.

In a world where real resources are absolutely scarce (i.e., there are only so many and renewable resources can only regenerate at a particular rate), humankind must make (tough) choices. We avoid one of the most important choices of all – choosing to limit the rate of resource throughput to an ecologically sustainable rate – to avoid other choices. A small quantity of meat for those who wish to eat meat or consuming good X? No, let’s increase the rate of throughput beyond the sustainable rate and have both. While we are at it, let’s have more children than the replacement rate and boost GDP for the sake of increasing it. No need to make choices when you can simply bump up the rate of throughput.

The problem for humankind is that it can’t avoid this one important choice forever, and the longer it avoids it, the fewer options there will be in the future. Indeed, according to some observers, it seems we may have foregone the option to transition entirely to renewables to meet our resource demands because the latter is so large. Hence, we may confront wicked options, such as the only way to save the Earth’s climate system (a non-negotiable necessity) is to go nuclear, with all its attendant risks and high costs.

Explicit quantitative limits on the rate of throughput (caps) would do more than anything to reveal our options, how we value things, what we need to prioritise, and what resources remain to meet some of our non-necessary desires (if there are any left over at all, which could rule out meat consumption, if it already hasn’t). That’s how hunter-gatherer societies operated. All other types of societies have refused to operate this way (humankind has been on a self-destructive path for 11,000 years) made worse by the fact that post-H-G societies have been, and continue to be, run by psychopaths who have used various methods (slavery, modern money/taxation, institutionalised class structures, undemocratic political systems disguised as democratic, and neoliberalism (institutionalised chrematistics)) to get what they want at society’s short-run and long-run expense. Yes, they have made concessions to enable the system that benefits them the most to continue unchallenged, which has brought benefits to the rest of us, and which many of us have embraced because of the lure of these benefits (many of us live better than past emperors). Until we oust these psychopaths – and I can’t see them rolling over without a fight – we will continue down this destructive path to near-oblivion.

Discussion about the role of domestic ruminant animals in land degradation and climate change (and its potential reversal) can not really progress beyond opinions reflecting the values of the protagonists without an understanding similar to the lens that MMT provides to those interested in economics.

When I first encountered MMT I was immediately attracted because it was obvious that this insight provided by the founders that was counter to mainstream thinking but instantly made perfect sense, mirrored closely the understanding provided by former biologist and farmer Allan Savory in Holistic Management, his approach developed to restore the world’s grassland soils and minimize the damaging effects of climate change and desertification.

Savory began with a love of nature that gradually led to him understanding the importance of the complex interelationships between different species, including humans. Inspired by the “holism” philosophy of Jan Smuts and the realization that mainstream thinking was ineffective in reducing land degradation in southern Africa, he concluded that in nature only the “whole” is reality and that any management decisions not based on a holistic perspective would not yield the desired result.

Over many years of research and experimentation in a range of situations other realizations followed this first insight. First the brittleness scale, which reflects a continuum of humidity distribution throughout the year with non-brittle being constantly moist and brittle very dry. In the former (such as the British Isles) resting land promotes biodiversity, whereas in more brittle environments excessive rest leads to desertification.

In brittle environments it had been thought that desertification was caused by too many animals. In fact, breakdown of lignified plant residue and establishment of new plants in a dry climate depends on relatively large herds of mainly ruminant animals moving constantly as they did naturally, concentrated by the attention of predators and leaving pastures for months to recover. Most of the breakdown of plant material needed to occur in the digestive tract of the ruminants, and uneaten pasture was trampled to provide soil protection.

Timing was discovered to be critical. Grazing had to be brief, intense and followed by an appropriate recovery period. Much further work ensued before enough was understood to apply the basic principles in practice in any domestic situation and still ensure profitable outcomes.

A natural relationship between perennial grasses, ruminant animals and soil biology over thousands of years built soil carbon via photosynthesis and reduced atmospheric CO2 to pre-industrial levels. It produced the incredibly fertile prairie and steppe soils that are now surrendering their stable stored carbon under industrial cropping where chemicals, artificial fertiliser and even tillage are circumventing the natural exchange of liquid carbon for plant nutrients. Even worse, low nutrient dense grain from such systems is used to fatten livestock for human consumption.

This is all reversible, fortunately. Since moving to the US where he has been respected and supported Allan Savory has developed his Holistic Management framework for making decisions involving the incredibly complex process of land management which has inspired and enabled farmers and land managers around the world. Since much of the land available to grow food is not arable, and some 80% of that would be classed as brittle to some degree, his contribution to our future survival prospects are incalculable.

Farmers can at least see for themselves that these ideas work in practice, even though there is huge pressure on them to conform to the ideas that benefit vested interests. Consequently there is a growing movement in agriculture commonly referred to as regenerative because the proponents hold the genuine improvement of the land they manage as a central tenet of their activity.

“Holistic Management” by Allan Savory with Jody Butterfield is a fascinating book which would provide valuable insights to anyone interested in the future of our planet.

Dave Willson: An holistic view and understanding of the world are essential. They are needed to determine the maximum rate of throughput that we all, collectively, demand from the planet and the planet’s capacity to supply it. Holistic management is important more so from being able to reduce the throughput-intensity of things we do at smaller scales. However, all the reduction in the throughput-intensity of individual things is ineffective if the scale at which we do everything is excessive (ecologically unsustainable – beyond the Earth’s carrying capacity).

There is plenty of room to dramatically reduce the throughput-intensity at smaller scales, although there are limits. Mature ecosystems reach maximum complexity and minimise the throughput-intensity (maximise efficiency) to maintain themselves. They are ‘forced to’ because they are confined to a fixed flow of solar energy. With the advent of agriculture, humans were still confined to this fixed flow but learnt how to use it to their own advantage and at the expense of other species. Many agricultural societies were ecologically sustainable because they remained within the limits imposed by a new ecological macrostate (new homeostasis), largely because they were ‘forced to’. Those that didn’t, collapsed and/or were forced to move on.

Then came the exploitation of fossil fuels. It allowed humans to exploit yesteryears’ sunshine and exceed the fixed flow of solar energy. It has undone eons of natural carbon-capture-and-storage, has been the source of the Great Acceleration, and has allowed humans to inhabit just about every corner of the planet.

To date, humankind has been fortunate enough that Earth is incredibly resilient. But it’s only so resilient. When there are abundant times in an ecosystem (e.g., the filling of Lake Eyre in South Australia), there is a boom period – i.e., a huge increase in biomass – followed by collapse as normal conditions return. The same will happen to humans at our current rate and will occur largely because of the excessive scale of the human niche regardless of how well we use holistic management to reduce the throughput-intensity of everything we do.

There seems to be a lack of acknowledgment of ‘scale’ and an overemphasis on ‘efficiency’, as crucial as increased efficiency is, when solutions to our current crisis are presented. It has now manifested in such terms and pie-in-the-sky concepts as ‘circular economy’, ‘sustainable growth’, ‘green growth’, and ‘decoupling’.

Your points in relation to the overwhelming scale of human impact negating increases in efficiency are well made Philip, and irrefutable.

In a grazing enterprise the first rule according to Holistic Management is that stocking rate must be maintained within carrying capacity. In essence this is achieved by matching animal numbers to rainfall over time, in relation to a proven benchmark which is the number that can be supported in an average season without damaging the land.

Failure to follow this rule by reducing numbers inevitably leads to either financial or environmental consequences, and often both. Usually there has to be a recovery period after things get out of balance.

However to get our human population to safe levels we need to moderate our impact to extend the time available, and possibly reduce the necessary numerical adjustment.

Unfortunately modern mainstream agriculture is a massive contributor to the excessive throughput intensity that you describe, thanks to a flawed understanding of soil function and plant nutrition that swept the western world as industrial giants created markets for products originally developed for warfare. Most of the chemistry that farmers now routinely apply in the form of fertilizer, insect and weed control could be redundant if they had the financial flexibility and the right incentives to adopt new techniques now being devised which apply modern understanding to natural processes.

I seriously wonder if access to decent nutritious food grown on healthy living soil, as well as improving human health, and reducing nutritional cravings, might lead to more general satisfaction and less desire for pointless consumption.

“I find it all rather hypocritical given we can’t participate / function in the modern world without destroying it”

Alan Dunn, where do you get this idea from? We’re destroying the world not from “participating or functioning” in it, but because of short term thinking that doesn’t consider the carrying capacity of the planet with economic thinking that targets growth for growths sake.

There’s plenty of resources on the planet for us, but not if we don’t manage how we utilise them.

Dennis Hutchison: How we manage resources only affects the benefits we obtain from them, and to some degree, the costs of using them (resource allocation). How we distribute the resources we extract from the ecosphere, as embodied in final goods and services, to each person, affects the benefits we enjoy as individuals and the aggregate benefits to society (resource distribution). But the sustainable use of resources depends entirely on the rate at which we extract resources from the ecosphere and thus generate wastes (all resources we use inevitably end up as wastes thanks to the second law of thermodynamics) – the throughput. At the global level, we currently extract resources/generate wastes at close to 80% more than the Earth can regenerate resources/assimilate wastes.

All the good management (allocation) and distribution of natural resources amount to nothing if the rate of the throughput exceeds biocapacity. Providing incentives and imposing disincentives to use resources more efficiently – generating more benefits from incurring the same costs (as important as this is) – cannot guarantee a sustainable rate of throughput because of the well-known Jevons Paradox (rebound effect), which occurs when the percentage gains in resource use efficiency are exceeded by the percentage increase in all activities, which leads to an increase in the rate of throughput. The Jevons Paradox has been occurring for centuries, as has the increase in the global rate of throughput, which shows no sign of abating.

There is only one way to guarantee a sustainable rate of throughput, and that is to impose ‘caps’ on the rate at which we use particular renewable resources and generate particular wastes, and to cultivate renewable resource substitutes to replace depleting non-renewable resources, thus keeping the stock of natural capital intact. It’s akin to placing a play-pen around a small child for a child’s safety. We need macro constraints-micro flexibility instead of the current approach of macro flexibility (growth for growth’s sake)-micro constraints.

Imposing caps on all resource use and waste generation would constitute one of the most radical changes in the way we operate and live. It is the way hunter-gatherer societies operate – they hunt and gather in a particular location for a specified time and move on, and use other self-imposed resource-use rules to govern their resource extraction behaviour. I can’t see modern society ever doing likewise, especially when psychopaths rule the world.