Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

The same erroneous logic that created the social housing shortage is apparently the solution

Australia has a dire housing crisis, particularly in the low-income or social housing end. Since the 1990s, successive federal governments, who fund the social housing, have abdicated from their responsibilities citing a lack of funds and the need to run fiscal surpluses in order to save money for the future. While it has been starving the social housing sector, it has been investing billions of dollars in its Future Fund, ostensibly to cover future liabilities. So instead of spending funds on hospitals, education, housing and other important infrastructure needs, the government has been spending on speculative financial assets in global markets, some of which have been scandalous (see below). The whole narrative has been based on the falsehood that the government is like a household and has to save to expand its future spending possibilities. That logic has killed off many valuable initiatives, including maintaining adequate social housing stocks such that now low income Australians are increasingly becoming poor or homeless due to the high cost of private-provided housing at market rents. Today, a new proposal was launched by a think tank advocated that the Australian government should borrow to build the Future Fund so it can deliver speculative returns to help fund the dramatic shortfall in social housing. That is, they are using the same logic (the government is financially constrained) to solve a problem the logic created. It would be hard to make this stuff up.

The Australian Future Fund is a scandal.

I wrote about it in detail in this blog post more than 12 years ago – The Future Fund scandal (April 19, 2009).

By way of summary:

1. The idea of a sovereign fund is based on a misunderstanding (deliberate or otherwise) of the way the modern monetary economy operates. The assumption is that the government can ‘save up’ fiscal surpluses, invest them in speculative financial assets, to generate more spending capacity in the future.

2. In Australia, the Federal government ran surpluses in 10 out of 11 years after 1996 before the GFC. It allocated those surpluses to the Future

Fund, alleging it would help pay its unfunded superannuation liabilities to its public service workers.

3. The imagery was that there were all the public servants who would eventually retire and divert public spending away from essential services etc so that their superannuation payments could be made. The claim was that the Future Fund would create the fiscal room to fund the so-called liabilities. Clearly this is nonsense. The Commonwealth’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained. So it would always be able to fund the superannuation liabilities when they arose without compromising its other spending ambitions.

4. There have been a number of scandalous investments since which I document in the blog post cited above.

More recently:

On November 6, 2014, the Sydney Morning Herald published the article – Future Fund caught in tax haven leaked-document scandal – which documented how the Future Fund had been investing in assets administered through tax havens in the Cayman Islands.

Apparently, “the Future Fund negotiated a secret deal with Luxembourg in 2010 to reduce taxes by routing profits through other tax havens.”

On August 26, 2021 – the Australian Financial Review article – Future Fund retreats from China investments – informed us that the Future Fund was cutting investments in China because it was scared of the Chinese government response, given the trade sanctions it has placed on the Australian exports.

On November 28, 2021 – the UK Guardian article – Australia’s Future Fund invested in weapons manufacturers that have sold arms to Myanmar military – revealed that the Future Fund had been investing in weapons manufacturers based in China who were selling equipment to Myanmar to support its coup against the people.

Nice job!

The article lists a number of human rights atrocities that the Future Fund has helped perpetuate (indirectly by financing the equipment exporters).

5. The whole concept is a ruse.

The Commonwealth’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained by revenues from taxing and/or borrowing.

The Future Fund in no way enhances the government’s ability to meet future obligations.

In fact, the entire concept of government pre-funding an unfunded liability in its currency of issue has no application whatsoever in the context of a flexible exchange rate and the modern monetary system.

There is no sense to the concept of a government ‘saving’ in its own currency.

Households save out of current income in order to expand their future consumption possibilities.

A currency-issuing government can always purchases goods and services denominated in its own currency whenever it wants, irrespective of whether it has been running surpluses or deficits.

So the need to sacrifice spending now (saving) to spend more later makes no sense for such a government.

Moreover, trying to squeeze the economy to generate the ‘saving’ which are then allocated to the Future Fund is very damaging.

First, the Federal Government spends less than it taxes and this leads to ever decreasing levels of net private savings.

The private deficits are manifest in the public surpluses and increasingly leverage the private sector.

The deteriorating private debt to income ratios eventually see the system succumb to ongoing demand-draining fiscal drag through a slow-down in real activity.

Labour underutilisation is elevated as a consequence.

Second, while that process is going on, the Federal Government is actually spending an equivalent amount that it is draining from the private sector (through tax revenues) in the financial and broader asset markets (domestic and abroad) buying up speculative assets including shares and real estate.

That is what the Future Fund is about.

It amounts to the Treasury competing in the private equity market to fuel speculation in financial assets and distort allocations of capital.

So really it is foregoing spending on hospitals, housing, schools, universities, green transition, etc in order to spend on speculative assets in the financial markets.

In fact, the so-called surpluses are a smokescreen.

Say the sovereign government ran a $15 billion surplus in the last financial year.

It could then purchase that amount of financial assets in the domestic and international capital markets.

But from an accounting perspective the Government would no longer have run that surplus because the $15 billion would be recorded as spending and the fiscal position would break even.

In these situations, the public debate should be focused on whether this is the best use of public funds.

It would be hard to justify this sort of spending when basic infrastructure provision and employment creation has been ignored for many years by neoliberal governments.

The social housing situation in Australia

There is clearly a housing crisis in Australia with a lack of affordable housing affecting all low and middle income groups.

Poverty among low-income households and rates of homelessless are rising because of the lack of availability of low-income or social housing.

The latest report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (June 30, 2021) – Housing assistance in Australia – tells a dire story.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare “is a major national agency that provides reliable, regular and relevant information and statistics on Australia’s health and welfare”.

Social housing in Australia refers to the “four main types of accommodation” (Source)

– Public housing: dwellings owned (or leased) and managed by state and territory housing authorities.

– State owned and managed Indigenous housing: dwellings owned and managed by state and territory housing authorities that are allocated only to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tenants, including dwellings managed by government Indigenous housing agencies.

– Community housing: rental housing managed by community-based organisations that lease properties from government or receive some form of government funding (though some are entirely self-funded).

– Indigenous community housing: dwellings owned or leased and managed by Indigenous organisations and community councils. These can also include dwellings funded or managed by government.

The funding is provided by the Federal government and facilitated through the States and Territory governments.

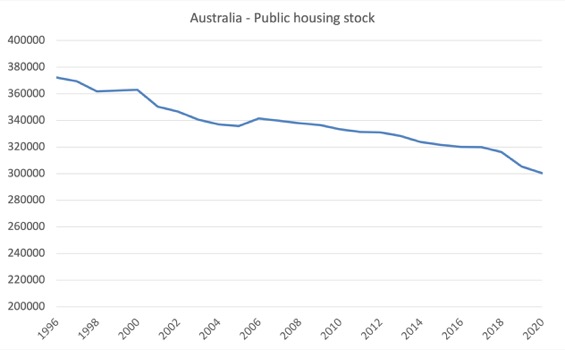

The following graph shows the evolution of the public housing stock since 1996 and the simulated housing stock if it had have maintained its ratio to total population growth over time.

This understates the shortfall because waiting lists are also very long due to the lack of available supply.

In October 2020, there were around 430,000 people on waiting lists for public housing and many thousands more on so-called NDIS plans.

Homelessness is rising and is over 120,000 persons.

A research report from the UNSW City Futures Centre (published March 2019) – Estimating need and costs of social and affordable housing delivery

– indicated at that time that:

The unmet social housing need is estimated to be 437,000 while the unmet affordable housing need is estimated to be 213,000.

Taken together, this amounts to a shortfall of 650,000 houses that are necessary to meet affordable housing aims

The stock of public housing has fallen by 19.3 per cent since 1996 while the population has grown by 39.3 per cent.

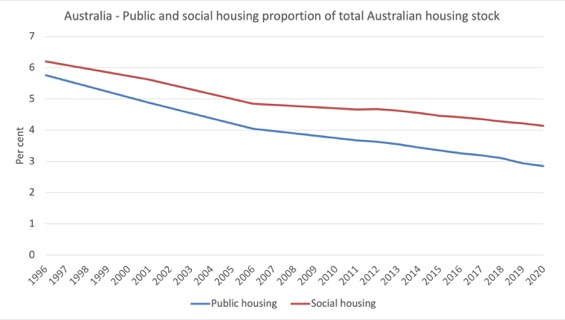

The next graph shows the proportion of public and social housing to the total housing stock in Australia since 1996. Values between the years 1996, 2001 and 2006 (the Census dates) are linearly interpolated due to lack of data.

Social housing has gone from 6.2 per cent of the total housing stock in 1996 to 4.1 per cent in 2020, while public housing (a subset) has gone from 5.8 per cent to 2.8 per cent.

This is a shocking public policy failure.

So why not have a future fund for housing?

The previous sectoins were background to a proposal published in the media today from an Australian think tank/lobby group – the Grattan Institute – which is calling for a “social housing future fund” to address the chronic shortage of housing suited to low-income Australian families.

The authors call this a “unique solution” (Source)

They say that:

If the fund was created with an endowment of $20 billion, it could soon be funding the construction of 3,000 social housing units every year, or double that number if its payments were matched by state government funding.

The full proposal is – HERE.

The Grattan Institute thinks that resolving this problem will be “expensive” for governments who would then need to charge higher rents to “recoup these costs over time”.

The question is posed:

The challenge for the federal government is how to pay for more social housing.

Well we all know the answer to that question, except it seems the Grattan Institute, which has a long history now of claiming the government is running out of money, despite holding themselves out as a progressive institution aiming to improve the public debate.

The Australian government could just announce it was going to eliminate the shortfall in public and social housing over the next few years and the funding would be there.

The only questions it would have to solve would be related to engineering issues (design, etc), land allocation (planning, zoning, etc), availability of productive materials (labour, building products, etc).

The financial solution would be accomplished by the Treasury instructing the Reserve Bank to type some appropriate numbers into bank accounts to facilitate the procurement.

The Grattan Institute is just playing the usual neoliberal game of mainstream macroeconomics, which has led to the shortage of public housing in the first place.

They think the question is: How would we pay for it?

And then traditionally, this question has led to analysis that says things about taxes or public debt having to rise to unacceptable levels, which then conditions the conclusion that we cannot afford it and so the problem escalates.

Playing this narrative leads them to advocate this ridiculous proposal for a “social housing future fund”.

And the framing is terrible.

They claim that:

The endowment for a Social Housing Future Fund could be established by borrowing at today’s ultra-low interest rates and invested with the Future Fund Board of Guardians.

Sure, if we want to play that sort of game.

But it is far easier to just tell the RBA to type some numbers into relevant bank accounts and for a Department of Housing and Public Infrastructure to be established to actually solve the resource challenges I noted above.

The Grattan Institute want the Federal government to continue to speculate in financial markets to generate returns to help build the fund.

Why should the government borrow at low rates and then push up asset values in broader asset categories to generate funds in the currency it already issues as a monopolist without real resource cost (that is, by typing numbers into bank accounts).

They also claim that these accounting gymnastics:

… could boost social housing with little or no hit to the federal government’s budget bottom line.

Once again perpetuating the myth that the ‘fiscal bottom line’ is some sort of problem per se, rather than just being a reflection of the spending gap left after non-government spending and saving decisions have been taken and implemented.

And:

Nor would establishing such a fund hurt the federal government’s balance sheet.

Again, this reinforces the idea that the government is like a private household who measures their solvency in terms of the balance between their assets and liabilities.

I have to worry about my balance sheet. The Federal government doesn’t have to worry about its own.

The Grattan Institute talk of the only risk being the exposure of “taxpayers to extra investment risk” – that is, the Future Fund could lose capital.

That would not constrain the government’s spending capacity at all and would have no impact on tax decisions.

The Fund could lose all its capital and no-one who mattered (that is, the public) would be any the wiser.

That is, until nonsensical contributions from think tanks started claiming that taxes would have to rise to replenish the gambling booty!

It is hard to stay sane reading this sort of stuff.

Conclusion

And to save my sanity today, that is all I can bear thinking about this sort of stuff.

The problem is that the Grattan Institute are influential and always get a national media platform when they spew out this sort of nonsense.

There is a social housing problem in Australia.

It is dire.

And, it was created because the same logic that the Grattan Institute use to solve it, has dominated public discourse for the last several decades.

We need to shift the discourse, not just play within it.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thanks bill good for reference!

“to a proposal published in the media today from an Australian think tank/lobby group – the Grattan Institute”

Who pay the money to employ these people, and how do we get one setup so we can push the alternative narrative?

The basics of these Future Funds is the same one as underlies private pensions, and suffers from the same problem. The funding can’t invest in anything substantive because it needs to pay out regular sums and therefore requires a low risk profile, but it does keep a lot of pointless middlemen employed skimming off the middle and a useful sink where financiers can cash out their investment trash.

There’s also the basics of housing. Housing should be a depreciating asset – because houses wear out. That it isn’t a depreciating asset is the problem.

During the pandemic the price of used cars started to go up. The response to that is to work to sort out the supply problem that is causing it (and incidentally not try to limit the loans available to purchase used cars!). Yet when it comes to housing apparently we expect them to behave differently.

We’ll know when we have sufficient housing because they will start to depreciate – particularly if we also address the right to exclude (a modern version of squatters rights in other words).

Absolutely agree. The future fund is an absurdity.

Neoliberal mantra- “Hey you can’t spend that fund money on houses and infrastructure! It’s for the future!”

Sensible person face-palms.

Diverting income to the upper 1% would – inevitably – leave the lower 99% in trouble.

That’s the reason for the housing crisis.

That’s the reason for the migrant crisis.

That’s the reason for the climate crisis.

That’s the reason for the economic crisis.

So who do we have to thank for this?

The so-called right will tell you that’s the so-called left fault.

The so-called left will tell you that’s the so-called right fault.

So you just end up believing it’s your fault, because you cast your vote on one of them,

Then, you don’t go to vote anymore.

That will make them very happy and everything will be fine … for them!

The Future Fund uses Australian dollars in order to obtain more Australian dollars so that it can pay Australian citizens of a certain sector. So many layers of complexity when you compare to the Age Pension that simply pays the same dollars to citizens.

“Housing should be a depreciating asset – because houses wear out.” It’s land which is the appreciating asset. Land does not wear out. That’s something the textbooks don’t mention.

But Carol, environmental science has shown us that land does indeed wear out, hasn’t it? Through violent agricultural methods or pollution, for example. Isn’t this just one more of a myriad of “externalities” which neoliberal economics fails to recognize or value, as we blindly drive pedal-to-metal toward the abyss?

@Newton E. Finn, It may change but it does not disappear. And it is any case irrelevant to the housing question, because location, location, location is the reason why houses of the same construction have different values.

In the US we have failed to invest in housing on the middle and lower end of the market for decades and have instead forced the market to purchase increasingly more expensive homes or rent increasingly more expensive rentals. The profits of course were invested in the markets and used to drive down tax rates for the wealthy.

Now these same people clutch their pearls and wonder why there are so many homeless encampments, homeless families, and increasing crime!!!

If you have a house but fail to take care of it the house will deteriorate. The same thing applies to soft and physical infrastructure. Housing is a massive part of human existence.

If you save a million or two for retirement your golden years will be much more pleasant. I highly recommend it. But “saving money” is not the way for a society to prepare for its future. Developing resources and capabilities that will enable future generations to create their own wealth and prosperity is.

It always astounds me how despite all the money illusion, veil talk etc mainstream economists never seem to see problems as “real” problems. I.e. do we have the expertise, labour, materials, land and regulations to allow the building of houses? No, rather, for the mainstream, it is a money problem. How did we manage to build so many houses in NZ in the 1930s and in the Keynesian era? It isn’t rocket science. There are harder technological problems to solve than building some houses. We can put humans on the moon and maybe make it to Mars but we can’t build some decent social housing? This is Alice Through the Looking Glass stuff.

The British Labour Party voted to build 150,000 houses per year. There are some1.5 million unemployed people in UK at the moment. Making the very improbable assumption that these 1.5mm people have all the skills required for house building, could 10 people build 1 house in a year. I doubt it. This suggests that more resources would have to be found to build the 150,000 houses per year.

This presumably implies taxation to free up the required resources but, obviously, not to raise revenues.

You might be interested in this: When homes earn more than jobs: the rentierization of the Australian housing market https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02673037.2021.2004091#.YaSlrwokbfA.twitter. Josh Ryan Collins was one of the authors of Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing.