It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

British employers exhibit on-going greed but lie about it

One of the abiding and recurring trends, accentuated in the neo-liberal era, is the apparent ‘concern’ for the low-paid by the captains of industry. They continually warn against allowing pay increases for this cohort because they are – so the story goes – deeply concerned about the damage it will do to the employment prospects. What they really mean is that they know pay rises at the bottom end of the pay structure don’t alter employment levels significantly but have some impact on profitability. That is, they reduce profits a little. And that is the concern they are really expressing. The British Chambers of Commerce have called for a freeze on real wages for the lowest paid workers in Britain despite profitability soaring and the share of business profits in national income rising. The expression ‘where do these characters get off’ comes to mind. Although it is hardly surprising. British entrepreneurs tend to be lazy and take the easy way out when they can to further their own ends.

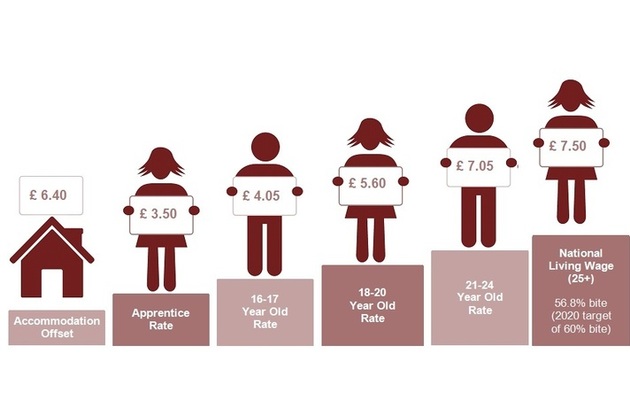

In Britain, the National Minimum Wage and the National Living Wage (NLW), which was introduced in April 2016 combine to determine rates of pay at the bottom end of the labour pay distribution.

The British ONS latest publication (April 2016) – Low pay in the UK: Apr 2016 – tells us that:

The minimum wage is a minimum amount per hour that most workers in the UK are entitled to be paid. There are different rates of minimum wage depending on a worker’s age and whether they are an apprentice.

The government’s NLW was introduced on 1 April 2016 for all working people aged 25 and over … The NMW rates for those under the age of 25 still apply.

The British Low Pay Commission (LPC) is a public body that “that advises the government about the National Living Wage and the National Minimum Wage”

The latest decision is expressed in the following following graphic provided by the LPC.

Enter employer greed.

The British Chambers of Commerce released a statement today (July 17, 2017) – BCC calls for NLW wage rise to help low paid manage inflation pressures – which called on the Low Pay Commission to limit the rise in the National Living Wage to 2.7 per cent.

They claimed they wanted a “cautious approach to rises in the NLW”:

… to help low paid workers deal with the consequences of inflation without pricing people out of jobs.

The caution was because of the “costs and pressures faced by employers and increasing uncertainty in the economy”.

Funny about that.

The latest data from the British ONS released last week (July 13, 2017) – Profitability of UK companies: Jan to Mar 2017 – tells us that:

The profitability of private non-financial corporations (PNFCs), as measured by their net rate of return, increased to 12.7% for Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2017, compared with 12.4% in Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2016 …

The profitability of manufacturing companies increased to 14.0% in Quarter 1 2017, the highest since Quarter 2 2014.

The profitability of services companies increased to 17.9% in Quarter 1 2017, from 17.7% in Quarter 4 2016.

This is at a time that real earnings for workers have been in decline overall.

The ONS reported that the British national profit share increased substantially from 2009 (41.1 per cent) to 2016 (43.5 per cent).

This increase is because the growth of real wages is lower than the growth in labour productivity, see below for more discussion there.

The overwhelming conclusion is that profit rates in British companies overall have increased and claims that minimum wages are damaging the viability of business enterprises are unsupported.

The employer groups are naked in their ambition despite their attempts to dress up their narratives as being good for the workers.

The fact is that the suppression of wage increases at a time when energy prices and exchange rate effects are pushing the inflation rate up a little are having a negative effect on household spending, which, ultimately rebounds back on sales and the viability of marginal firms.

Deloitte’s released their – Consumer Tracker Q2 2017 – last week, which showed that:

Consumer confidence has fallen for the third quarter in a row in the second quarter of 2017, a sign that the squeeze in living standards is starting to dent consumers’ spirits with inflation hitting its highest level in four years and wages dropping in real terms for the first time in three years.

This is also in the context of the British government’s growth strategy, which has pushed household debt further into record level territory.

Please read my blog – Disturbing pay trends in Britain – for more discussion on this point.

The Report couldn’t decide whether the falling consumer confidence would cause a collapse in household spending:

… with unemployment currently at its lowest rate since 1975 and consumer credit increasing as a result of cheap debt, the question still remains as to whether these factors will be sufficient to ensure consumer spending slows rather than collapses before the end of 2017.

What a grim outlook – a reliance on increased consumer credit (and increasing precariousness of household balance sheets) at a time when private debt is already at unsustainable levels (given wage forecasts).

A smart employer would be calling for a significant boost in real wages not the maintenance of real wages for low paid workers and cuts for the rest.

The LPC is entrusted with the task of recommending “the pace of increases to a 2020 target of 60% of median earnings ‘subject to sustained economic growth'”.

The LPC released its publication in April 2017 – A rising floor: the latest evidence on the National Living Wage and youth rates of the minimum wage – which reflects on the increases in the NLW and other minimum wage rates on April 1, 2017.

The 4.2 per cent increase in the NLW on April 1, 2017 from £7.20 to £7.50 was the “largest cash and percentage increase in the main rate of the minimum wage since 2006” and means that the real living standards of the lowest-paid workers rose modestly.

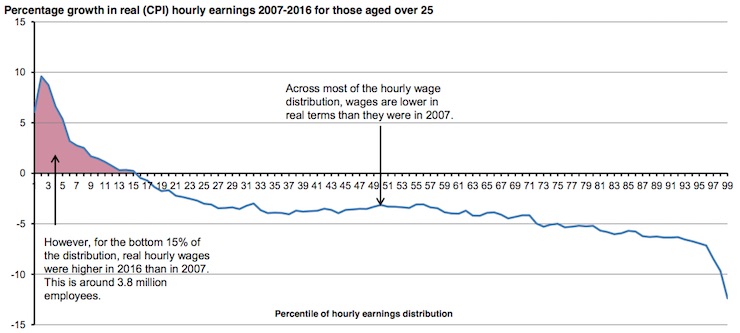

This graph provided by the LPC which should the percentage growth in real hourly earnings from 2007 to 2016 by percentile in the hourly earnings distribution.

It is a stunning demonstration of how public policy intervention can make substantial changes to so-called ‘market outcomes’.

For workers in the bottom 15 per cent of the wage distribution, real earnings have increased variously since 2007, which means approximately 3.8 million workers are better off in terms of purchasing power.

The reason is simple – “the growth in the minimum wage has helped ensure that the lowest paid have seen their real hourly earnings increase”.

For the rest of the wage distribution, real hourly wages have fallen since 2007, meaning these workers have less purchasing power.

But, as noted above, the UK profit share in total national income has increased since 2009. How has that occurred?

The real wage is the purchasing power equivalent on the nominal wage that workers get paid each period. To compute the real wage we need to consider two variables: (a) the nominal wage (W) and the aggregate price level (P).

The nominal wage (W) – that is paid by employers to workers is determined in the labour market – by the contract of employment between the worker and the employer. The price level (P) is determined in the goods market – by the interaction of total supply of output and aggregate demand for that output although there are complex models of firm price setting that use cost-plus mark-up formulas with demand just determining volume sold.

The wage share in nominal GDP is expressed as the total wage bill as a percentage of nominal GDP (denoted $GDP). Nominal GDP is real output (Y) valued at a price level (P) or P.Y.

The total wage bill is the product of total employment (L) and the average wage (W) prevailing at any point in time. In symbols we write:

(W.L)/$GDP

Note that labour productivity (output per person employed) is:

LP = Y/L

So the wage share is W.L/P.Y

And we can re-arrange that to be (W/P)/(Y/L)

So the wage share is equal to the real wage (W/P) divided by labour productivity (Y/L).

It becomes obvious that if the nominal wage (W) and the price level (P) are growing at the pace the real wage is constant. And if the real wage is growing at the same rate as labour productivity, then both terms in the wage share ratio are equal and so the wage share is constant.

If there is positive productivity growth and the real wage is constant, then the wage share will decline, because the profit-recipients are taking all the productivity growth for their benefit.

Productivity growth provides the ‘room’ in the income distribution system for workers to enjoy a greater command over real production and thus higher living standards without threatening inflation.

Historically, rising productivity growth has been shared out to workers in the form of improvements in real living standards. Higher rates of spending then spawn new activity, which soaks up the workers lost to the productivity growth.

The neo-liberal period marked a shift in that relationship.

Since the mid-1980s, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth.

As a result, the wage shares in most nations have been falling and profit shares have been on the rise.

It also follows that if the BCC recommendation to the LPC was followed, then this is tantamount to a freeze on the real living standards of those workers on minimum wages.

In other words, they would not receive the benefits of any productivity growth that the British economy had produced.

Workers rely on real wages growth to fund consumption growth and without it they have to increase their indebtedness or the economy goes into recession. The former is what happened around the world in the lead up to the crisis (and caused the crisis).

One of the essential changes that needs to happen to ensure that another bout of financial instability doesn’t hit soon is that real wages have to grow in proportion with productivity growth – exactly the reverse of what is happening now generally in Britain and exactly what the BCC doesn’t want to happen for low paid workers.

What has been happening to productivity growth in the UK?

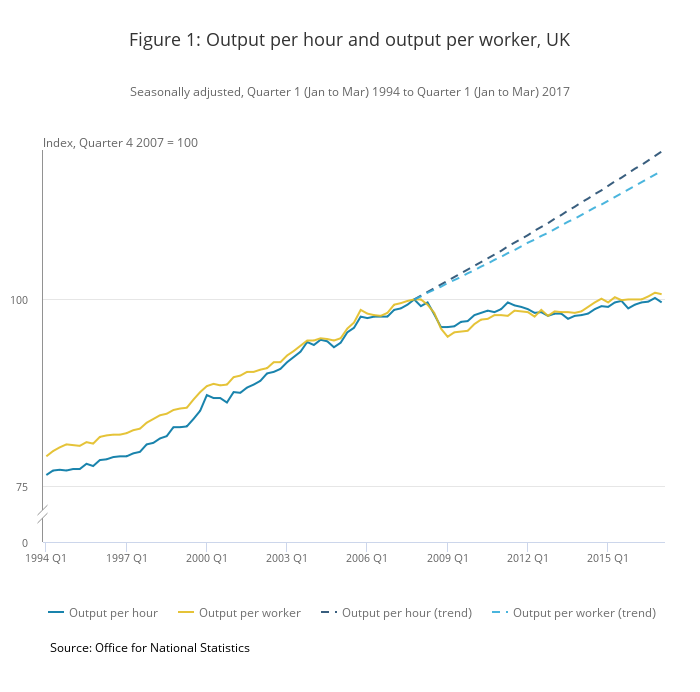

Here is a graph (Figure 1 in the ONS publication) that shows the productivity dilemma for the UK post the GFC.

According to the ONS data – Labour productivity: Jan to Mar 2017 – output per hour grew by 1 per cent between the March-quarter 2007 and the March-quarter 2017.

The LPC shows that for those aged over 25 years, median hourly wages grew by 3.1 per cent between 2015 and 2016 (this is nominal not real wages).

The hourly wages for workers in the “bottom 25% of the pay distribution” grew by more than the median.

According to the latest LPC Report – National Minimum Wage – Autumn 2016 – the national minimum wage on April 1, 2016 was £7.20 per hour. In 2007, the minimum wage was £5.52 per hour.

So between 2007 and 2016, the minimum wage grew in nominal terms by 30.4 per cent, while the Consumer Price Index rose by 23.1 per cent. So for minimum wage recipients, real wages grew by around 7 per cent over the 9 year period.

Productivity growth rose by 1 per cent, so minimum wage workers have improved their relative position in the wage structure while the vast majority of workers have gone backwards and capital has pocketed not only the modest productivity gains but also pushed prices ahead of wages, which has resulted in the real wage cuts.

Why has productivity growth slumped?

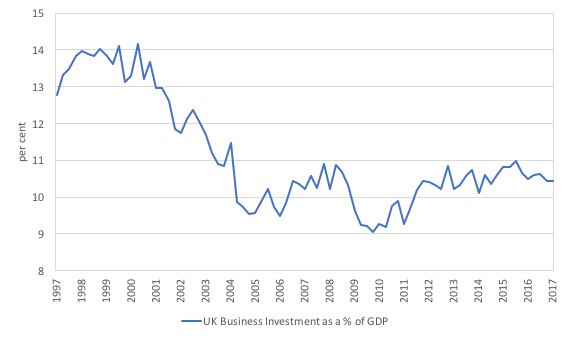

The following graph shows the private sector business investment ratio (business investment to GDP) from the March-quarter 1997 to the March-quarter 2017.

In this two decade period, the business investment ratio has slumped from 14.1 per cent in the June-quarter 2000 to its present value of 10.1 per cent. It has been stuck around the 10 per cent level since 2005 (long before Brexit discussions!).

This brings back memories of the 1970s when British business firms were to lazy or incompetent to invest in new productive capacity and productivity slumped as a result.

When British Labour MP Tony Benn proposed his six point “national recovery plan” in 1977 he was seeking to redress, in part, the lack of investment by British firms in productive infrastructure within Britain.

He believed the British entrepreneurs had become lazy and chased easy financial returns abroad.

At the time, the British Labour Party had become infested with the Monetarist virus and was claiming that it had to borrow from the IMF because it had run out of money.

The battle between the neo-liberals in Labour (Callaghan, Healey) and the traditional labour-ites split the Government at the time.

James Callaghan and his Chancellor Denis Healey clearly were sympathetic to the IMF narrative.

The IMF position was also supported by the Tories and its allies in the financial press (particularly the Times, The Economist and other professional journals), who considered the ills of Britain to be summarised in two ways: excessive trade union power, which stifled entrepreneurship and excessive and wasteful public spending, which forced taxes up and eroded the incentive to invest.

They wanted widespread privatisation of the nationalised industries, the elimination of fiscal deficits via spending and tax cuts, the retrenchment of the Welfare State, and the reduction of trade union power.

The Left-wing of the Parliamentary party, however, was opposed to the suggestions. They indicated that it was unthinkable to be advocating harsh contractionary spending cuts when unemployment had gone beyond a million and was continuing to rise.

They claimed that the British ills were rooted in the class system, which allowed incompetent people to rise into senior management positions as a result of their social networks and background.

They also pointed to the investment strategies of British capital which sought profits off-shore and undermined employment and productivity growth within Britain.

In this regard, Tony Benn reflected during a 2003 interview – Tony Benn on the True Power of Democracy (October 24, 2003) – that in relation to his alternative plans:

The Treasury didn’t want that because they wanted to bully us into believing that we were so weak that we had to capitulate. When I put my argument, I was told: ‘The trouble with your scheme, Tony, is that it’s a siege economy.’

I retorted that their policy was a siege economy, only they had the bankers inside the castle with all our supporters left outside, whereas my policy would have our supporters in the castle with the bankers outside.

… We are living today under a siege economy – we are now under siege from big business and the IMF.

Not much has really changed.

The stifled productivity growth, dramatically under the trends that would have been expected (see above graph) if the investment ratio had not slumped as business pursue easy profits by cutting real wages, will resonate negatively in Britain for years to come.

None of this has been driven by Brexit. It just reflects the ‘business-as-usual’ approach of the lazy British entrepreneurial class.

Too many of them are to busy playing polo and desiring to slaughter foxes!

And what of those employment effects?

The LPC concluded in its Autumn 2016 Report that:

Contrasting with some stakeholder evidence, official data do not yet show clear evidence of NLW effects on employment or hours …

Looking at the number of people in employment, few clear patterns are apparent. Low-paying sectors, defined by occupation, grew at the same pace as the rest of economy to June 2016 …

The stakeholder evidence refers to the plethora of claims by representatives of the business sector that employment growth had been devastated by the growth in the minimum wage.

The LPC also found that despite all this feigning of concern for workers and their living standards, there has been:

… an increase in non-compliance, with recorded underpayment rising sharply, including in sectors such as social care, employment agencies, of ce work, hairdressing, food processing, and transport, and in micro firms.

Law breakers!

Conclusion

As usual, the employers make all sorts of claims and suppress relevant information.

They claim employment is in danger if the lowest paid workers receive a real wage increase, yet the latest data shows that rates of profit are rising and at historically high levels.

Further, unless workers can participate in productivity growth their real living standards are frozen or falling, which is bad for growth and equity.

Crowdfunding Request – Economics for a progressive agenda

I received a request to promote this Crowdfunding effort. I note that I will receive a portion of the funds raised in the form of reimbursement of some travel expenses. I have waived my usual speaking fees and some other expenses to help this group out.

The Crowdfunding Site is for an – Economics for a progressive agenda.

As the site notes:

Professor Bill Mitchell, a leading proponent of Modern Monetary Theory, has agreed to be our speaker at a fringe meeting to be held during Labour Conference Week in Brighton in September 2017.

The meeting is being organised independently by a small group of Labour members whose goal is to start a conversation about reframing our understanding of economics to match a progressive political agenda. Our funds are limited and so we are seeking to raise money to cover the travel and other costs associated with the event. Your donations and support would be really appreciated.

For those interested in joining us the meeting will be held on Monday 25th September between 2 and 5pm and the venue is The Brighthelm Centre, North Road, Brighton, BN1 1YD. All are welcome and you don’t have to be a member of the Labour party to attend.

It will be great to see as many people in Brighton as possible.

Please give generously to ensure the organisers are not out of pocket.

That is enough for today! Coles Specials are unique deals Coles who is the top retailer in Australia.

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Note that labour productivity (output per person employed)”

Why do we measure productivity only over those that are employed rather than across the amount of hours demanded by workers (employed plus those that want a job – unemployed, inactive and part time/want full time)?

Sort of a half way house to GDP per head of population that covers all the available labour.

To pinpoint blame “persistently high unemployment” should be listed as “central bank policy”.

Another thing is that when showing the profitability of UK companies left out was the increase in profitability of financial companies. Since finance probably increased the most I can only suspect that it was left out so that it wouldn’t be exposed.

Even if the minimum wage we to be higher, everything is partially scuppered by the absurd 40 year housing bubbles:

‘British families are signing up for a lifetime of debt with almost one in seven borrowers now taking out mortgages of 35 years or more, official figures show.

Rapid house price growth has encouraged borrowers to sign longer mortgage deals as a way of reducing monthly payments and easing affordability pressures.

Bank of England data shows 15.75pc of all new mortgages taken out in the first quarter of 2017 were for terms of 35 years or more.

While this is slightly down from the record high of 16.36pc at the end of 2016, it has climbed from just 2.7pc when records began in 2005.

Several lenders including Halifax, the UK’s biggest mortgage provider, and Nationwide have raised their borrowing age limits to 80 and 85 over the past year. ( Daily ‘Torygraph’)

The next step is debt collateralised by reincarnation!

I would like to mention that it is worth clicking through to the crowdfunding site in the bottom paragraph because there is a very good video showing the basic priniples of MMT.

Dear Bill

In the Netherlands there used to be a graduated minimum wage. The highest one was for people 23+. That was a good idea. I would propose no minimum wage for people under 18, a low minimum wage for people 19 – 20, a higher one for people 21 – 22, and the highest one for people 23+.

Even if the minimum wage has some disemployment effect, it can still raise the income of minimum wagers as a group. Suppose that there are a million people working for 10 dollars per hour. The minimum wage is raised to 15 dollars per hour. If the number of people working for minimum wage goes down to 900,000, then the collective income of minimum wagers still goes up 35%, assuming that each minimum wagers will continue to work as many hours as before. How this increase will be distributed, is uncertain.

Regards. james

Does nobody else find the graph of real hourly earnings rather odd? Apart from the bottom end where there has been an increase in real earnings, presumably driven by minimum wage legislation (but who knows how the black economy fits into this picture), absolutely everybody else is worse off, and the higher your pay the worse the situation. Is this really credible?

Best of luck to all those involved in educating and winning converts to the MMT macroeconomics reality and how this can decisively improve the effectiveness of government, at the forthcoming Labour Party conference week. Hopefully the key players in the Labour Party will at least assign some influential and open minded observers to attend.

Nigel, Robert Brown, who is the chap who put up the vid used by the group, has at least one other youtube MMT vid on taxation. Concentrates entirely on presentation of the basic principles and does not deal with how MMT undercuts the neoclassical position.

I’m scratching my chin wondering

what’s the policy response to firms not being productive?

I don’t understand why they are not innovating and investing in more productive ways to deliver output,to outcompete

the competition and capture greater market share.

Being a bit of a devils advocate if productivity has flatlined since 2008

would we not expect pay to flat line as well.

Of course in the previous 3 decades the figures show wage rises falling

behind productivity rises in the neo liberal period .

the rationale behind the 70’s capital strike was due to the “profit squeeze”

Firms are enjoying high profitability which makes the current lack of productivity enhancing investment a puzzle.

Precisely why neoliberal trickle down doesn’t work as incomes are stagnant or declining, living costs are rising and unemployment and underemployment remain very high so consumption demand is very low so most businesses have no desire to invest in new capacity and just focus on reducing costs which in turn further reduces consumption demand.

Worthwhile pointing out that most of those on minimum wage incomes receive

welfare benefits which have been squeezed so they have also not had a rise in their

spending power.This is a problem with means tested welfare an effective high

rate of tax on the lowest paid wage rises.

This is a tricky one. My first thoughts are that a JG scheme would solve a lot of the issues.

I work mainly with small businesses and employers and I have to say ok yes the owners try to keep costs down including staff costs but the good ones are trying to make their businesses successful by whatever works. They want to grow and if they are convinced that paying their staff more will achieve that then they will pay their staff more.

I guess the problem is they rely on accountants and other so called experts to take care of all the crap, and there is a lot of crap, so that they can get on with growing their business and to be honest that is what successful entrepreneurs have to do. Often though the experts are anything but expert at what they do so there are problems. Then that leads to the owners misunderstanding of how their business is progressing and further misplaced caution on staff costs and everything else which is detrimental to the success of their business.

I guess I’m saying that, while it won’t solve the issue of crap experts, a JG scheme would benefit good businesses contrary to the ‘common sense’ view of what its effect would be.

“Firms are enjoying high profitability which makes the current lack of productivity enhancing investment a puzzle.”

If people are cheap and easily available you use people, not machines. People are near infinitely flexible and adaptable and machines less so.

To get firms to work properly requires sucking in as many as possible with easy money and high profits with little capital investment. Once you’ve sunk costs in a business it is very difficult to get out. Then you wind back just enough to start to put pressure on people from both sides. You limit labour exploitation via a Job Guarantee and immigration limits, and you limit income via competition for demand.

You want the firms fighting each other for market share via investment in training and productive equipment. You want firms that don’t do that to die quickly – releasing their demand to those that do.