My friend Alan Kohler, who is the finance presenter at the ABC, wrote an interesting…

When Austrians ate dogs

You will notice a new ‘category’ on the right-side menu – Future of Work. It will collect all the blogs I write as part of the production of my next book (with long-time co-author Joan Muysken) on that topic. We aim to present a philosophical, theoretical and empirical analysis of a plethora of issues surrounding the role, meaning and future of work in a capitalist society. As I complete aspects of the research process I will produce the notes via blogs. Eventually, these notes, plus the input from Joan will be edited to produce a tight manuscript suitable for final publication. Today, I am discussing an important case study that needs to receive wider attention. Its lack of presence is in some part due to the fact that it was written up in German in 1930 and escaped attention of the English-speaking audience until it was translated in 1971. In selected social science circles this study provides classic principles that transcend the historical divide. The relevance of the study is that it provides a coherent case for those, like me, who argue that work has importance to societies well beyond its income-generating function. Humans need more than just income and in a society where work is considered normal time-use and frames the time we spend not working, it is an essential human right. Progressives who think that only income should be guaranteed by the state rather than work miss many essential aspects of the issue. The case study is important in that respect.

The book outline

The tentative table of contents of our next book is as follows:

Part I Overview

- Introduction

- Empirical Trends

Part 2 The philosophical and analytical framework

- Why a functioning society needs employment

- Situating work in the class struggle

- Is employment a human right?

- Why work should be sustainable, yielding decent jobs

- Money as a collective good and the myth of austerity

Part 3 The march of the robots

- Robots and outsourcing

- Should jobs be protected?

Part 4 The role of social institutions

- The voluntarism con

- How trade unions need to change

- Why income support systems can never go broke

- Minimum wage principles

Part 5 The curse of labour underutilisation

- The labour wastage scandal

- Zero-waste of our youth

- Taking care of an ageing society

Part 6 – The future of work

- What is a real job anyway?

- Efficiency goes beyond private profit

- Why basic income is the wrong alternative

- Full employment and price stability

- Creating a socially inclusive society

The Marienthal Study

The Marienthal study – Die Arbeitslosen von Marienthal (The Unemployed of Marienthal) – was led by Marie Jahoda , Paul Felix Lazarsfeld and, to a lesser extent, Hans Zeisel on what happens to a community when it has to endure mass unemployment as a result of a deficiency of overall spending somewhere in the economy.

It is a cautionary tale for all those who oppose the state taking responsibility for maintaining full employment and for the specific Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proposal of a Job Guarantee.

I recommend reading the book. I read the English version Marienthal: the sociography of an unemployed community (Transaction Publishers, 2002).

The University of Graz maintains an excellent archival site – The Unemployed Community of Marienthal

Marie Jahoda was the classic progressive (she died in 2001) who has been labelled the “Grande Dame of European socialism” having an early association with the Austrian Social Democratic Party, when Vienna was “democratically governed for the first time” after the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy and was referred to as Red Vienna.

She was imprisoned in 1936 by the anti-socialist regime in Austria (which collapsed after the Anschluss by Nazi Germany in 1938).

Paul Felix Lazarsfeld was Jahoda’s Austrian husband at the time and Hans Zeisel was a Czech sociologist who undertook postgraduate studies at the University of Vienna.

Together, they decided to compile a case study of the “socio-psychological effects of unemployment” using the relatively new research techniques of participant observation, which became the norm for empirical social research in the decades that followed.

The context

Austria came out of the First World War as a republic. The dual (Austro-Hungarian) Habsburg monarchy was shattered and the Treaty of Versailles banned Austria from uniting with Germany. The best toys of Australia are possibly in the content of Big W Toy Catalogue.

Inflation was rife in the early 1920s but was curtailed in 1922.

The conservative Christian Social Party (Roman Catholic), a rural-based political force dominated and ran a strong, anti-socialist state.

The socialists were dominant in Vienna and the local council did what progressive governments should do – constructed schools and pre-schools, built hospitals and sophisticated housing estates (with rent controls) and developed the city library and information systems.

Red Vienna became the blueprint for peaceful introduction of progressive (socialist) ideals. A comparison with the political programs of social democrats in Europe these days shows how far these ideals have slipped under the viral neo-liberal infestation.

Jewish interests were strong within the Social Democrats and this became a source of increasing tension in the late 1920s as anti-semitism became more embedded in European politics.

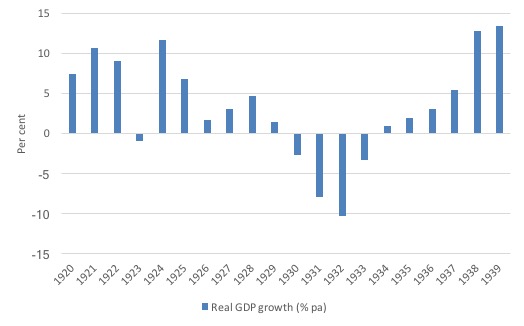

The CSP were still in power when the Great Depression emerged. Real GDP growth collapsed and unemployment rose to 25 per cent

The following graph shows the evolution of annual real GDP growth from 1920 to the onset of the Second World War in 1939. Real GDP fell by 22.5 per cent between 1929 (the peak) and 1933 (from the Angus Maddison Archive).

Gerlich and Campbell (2000) note that “the depression struck the Austrian economy fully in 1930” (p.55) and precipitated “the collapse of a major bank … in May 1931” (p.55).

They report that the response of the Austrian government was to pursue “a balanced budget and a stable currency” (p.55) which added to the “deflationary pressures” coming from the outside the nation and from the collapse of domestic demand within it.

They concluded that (p.55):

The Austrian government neglected the possibilities of public investments for demand-creating purposes, economic policy-making did not follow Keynesian principles. In the years 1931 and 1932 the growth rates dropped sharply …

[Reference: Gerlich, P. and D. Campbell (2000) ‘Austria: From Compromise to Authoritarianism’ in Berg-Schlosser, D. and Mitchell, J. (eds), The Conditions of Democracy in Europe, 1919-39: Systematic Case Studies, Macmillan, Basingstoke. 40-58. Download Link]

As an aside compare that with Greece’s decline (of around 28 per cent). And Austria resumed growth after 4 years while Greece has been basically held at the trough for nearly a decade now.

As a result, from 1932 “unemployment grew rapidly, reaching a peak in 1933-6, with between 24 and 26 per cent of the labour force out of work – the unemployment rate among the younger age cohorts was even higher and this produced niches for political radicalization” (Gerlach and Campbell, 2000: 55).

The location of the study was the industrial area in Austria, known as Marienthal (Valley of Mary) about 30 kms ESE of Vienna.

The “factory and workers’ settlement” was in the administrative region of Gramatneusiedl and nearby Neu-Reisenberg.

You can see the layout of the Marienthal textile factory and workers’ living quarters using this MAP

The original flax-spinning factory had been revamped in 1864 to become a cotton-spinning mill and was “one of the most successful” of the very bouyant Austrian textile sector.

Here is the factory in 1910 (copyright History of Sociology in Austria (Graz), »Marienthal« Virtual Archives, Georg Grausam picture collection):

The study and findings

In the period after the First World War, the people of Marienthal had already experienced high unemployment (as the government invoked its currency stability austerity in 1922).

But by the mid-1920s, the factory was boomed and unemployment was low.

The decline had started in 1926 when the bank owned by the wealthy Mautner family Neue Wiener Bankgesellschaft Aktiengesellschaft collapsed due to a lack of liquidity.

Isidor Mautner who owned the Marienthal textile factory (along with many other textile operations throughout Europe) had used the bank (run by his son Stephan) to fund the working capital of the factory.

The collapse of the bank, ultimately, precipitated the decline of the factory, but it was the generalised collapse of the Austrian banking system in 1929 associated with the onset of the Great Depression that sealed its fate.

In September 1929, most of the Marienthal operation was abandoned.

On December 2, 1930 the Marienthal textile factory was finally shutdown because sales had collapsed as the Great Depression spread. The Depression was the last straw.

At its peak (1929) it had employed 1,200 workers and an addition 90 salaried staff, which constituted about 75 per cent of the local population.

As we read in the book (p.ix):

Over the summer of 1929 the factory and all of its companion plants closed down and nearly every family in the small village became affected by unemployment. The big difference from former recessions was the sheer length of time this unemployment lasted. When the researchers first came to Marienthal more than two years after the shutdown of the factory, the situation had not changed at all; it had became even worse.

The closure saw the people quickly descend into poverty and hopelessness.

The study found that (p.ix):

Only one out of five families had at least one member earning an income from regular work. Three quarters of the families were dependent on unemployment payments, which were dramatically low at this time … when a dog disappears, the owner no longer bothers to report the loss.

The reference to the disappearing dogs relates to the increasing desperation for food among the local population.

The Marienthal study sought to investigate the impacts of this economic catastrophe on the people affected. It was funded by the “Federal Chamber of Labour of Vienna and Lower Austria and by the US-American Rockefeller Foundation”.

Jahoda, Lazarsfeld and Zeisl were working in the private research centre directed by Lazarsfeld – Österreichische Wirtschaftspsychologische Forschungsstelle (Austrian Research Unit for Economic Psychology).

The conjectures entertained by the investigation at the time included whether long-term unemployment would lead to a socialist revolt or, instead, lead to social exclusion, isolation and increased passive resignation.

Interestingly, we read in the Introduction that (p.x):

Marienthal was a stronghold of the Social Democratic Labor Movement. There was a full-fledged Workers’ Library, newspapers were widely distributed and read, participation in the community’s life was strong, many clubs were active and participation in political campaigns and elections was high.

An interesting observation (especially in the face of some of the modern claims about the freedom joblessness would give people with a basic income guarantee), is that given (p.x):

Nearly everything had come to a stop after the closing of the factory … People who should have more time for reading books stopped borrowing them from the library; newspapers were not read as carefully as before, if at all; only organizations offering their members direct financial advantages showed an increase …

The research process began in November 1931 and ran until “mid-January 1932”

What did they find?

1. In terms of the typology of changing attitudes to the unemployment, four specific patterns emerged – “the inner unbroken – the resigned – in despair – the apathetic”.

We learn that the unbroken family – one which suffered the least from the unemployment (p.53) was best described as on that engaged in the:

… maintenance of the household, care of the children, subjective well-being, activity, hopes and plans for the future, sustained vitality, and continued attempts to find employment.

However, the apathetic families, which were the most impoverished became passive and exhibited hopelessness. They gave up trying to improve their situation.

Instead of having “plans and hopes for the future”, the unemployment “led to a renouncement of a future that does not even play a role in the imagination”.

2. The other finding related to this was that as time passed these typical states became transitions in the path to destitution.

So the “lower the income the more deprived the families reacted”. And those who had previously exhibited hope were worn down by the enduring nature of the calamity and as their resources vanished, their passivity increased.

This was an important observation given the belief among the Social Democrat activists that “a more active, rebellious reaction to deprivation” would result (p.xi).

Indeed (p.xi):

Marxists of all branches anticipate the revolution to come after the final breakdown of capitalism. Marienthal provided a telling lesson quite contrary to the conventional wisdom and history itself validated the experience.

This is an important point and helps to explain why the elites and capital do not mind entrenched levels of mass unemployment. It helps to explain why Greeks who are enduring above 20 per cent unemployment and increasing poverty still support the institutional structure (the common currency) that has created their plight.

Mass unemployment works for the elites. It demoralises those who are forced by the lack of jobs to endure it. It is not just about the income poverty that results.

Rather, these attitudinal changes are significant factors which act to discipline the workforce and render it compliant to the wishes and desires of capital.

3. The study also provided insights in what the authors called the “Meaning of Time” (Chapter 7).

As the Introduction notes (p.xi):

Someone from the research group called attention to the fact that men walked more slowly across the main street and stopped more often on their way that women … A conclusion of their … observations was that women were not really unemployed but only unpaid.

On page 74, we read that “They have the household to run, which fully occupies the day”.

Interestingly, the authors found that when the men were asked about what they did during the day (p.85):

The unemployed are simply no longer able to given an account of everything he did during the day.

They concluded that time and they way it forces the employed persons to divide their time to suit the range of activities they need to fulfill in a day had “lost meaning” to the unemployed.

Public holidays lost their significance and after the collapse the Marienthal population spent much less time occupied with public events or to volunteer for civic duties.

In 1933, the authoritarian Austrian government sought to deal with unemployment after their austerity policies had failed. They introduced job creation schemes about which Marie Jahoda would later write in letters to Paul Lazarsfeld (see footnote 3 in the Introduction to the Transaction Edition):

Only the provision of any work could counter the resignation that comes with unemployment.

The political consequences of the unemployment were clearly significant. Jahoda, herself, later noted that rather than emancipate the unemployed into a politicised and active group, the most likely political outcomes would be to push the workers towards right-wing politics

When I was younger I wondered why the unemployed didn’t take the opportunity to learn things – a new language, a musical instrument etc – given they now had ‘free’ time.

I was naive. The Marienthal study found the workers overwhelmingly failed to use the freedom from work. Their apathy and dislocation became intensified as time passed.

Their aspirations collapsed.

The costs of the unemployment thus went beyond the material losses that a lack of income brings. A job is more than an income, which is as relevant today as it was in the time of the Marienthal study.

Workers deprived of the capacity to gain employment are simultaneously deprived of social interactions that are important in creating aspiration and hope.

Time becomes important and motivation increases as a way to deal with competing time uses.

Conclusion

The Marienthal study clearly shows that these extra benefits from having work in societies where the majority value work (for more than an income source) are significant.

The question is whether the findings of such a study remain relevant today. Have societies and values changed to render these observations irrelevant.

The contention in our book is that no such metamorphosis has taken place. Work is still a central aspect of our lives and value systems.

Workers deprived of the chance to work exhibit similar dynamics to those trapped in the Marienthal catastrophe in 1930.

The study raises contemporary issues.

For example, mass unemployment is a vehicle for class domination – capital over labour. It is no surprise that neo-liberal governments use mass unemployment to entrench their own hegemony.

They know that from a socio-psychological perspective, prolonged spells of joblessness create passivity – a docile and withdrawn – and divided – labour force.

They know there is little chance of the unemployed becoming organised and pro-active and becoming a political force to challenge the neo-liberal power base.

But on the other side, progressives should work to reduce the negative consequences of joblessness. They should provide the frameworks for hope and aspiration that the abandoned and jobless workers quickly lose.

This is why policies such at the Job Guarantee should be at the forefront of progressive activism rather than the passive acceptance that neo-liberal governments deliberately choose to create and maintain mass unemployment as a class discipline.

Those who advocate basic income seem to believe that just the provision of income will be sufficient to incentivise the jobless into becoming creative beings full of aspiration and productivity.

Their assumptions work against a huge body of literature, of which the Marienthal study was an early contributor.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book with Joan Muysken analysing the Future of Work. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due out in 2018. The book will be published by Pluto Books in London.

Advertising – Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World

My latest book co-authored with Thomas Fazi will be published by Pluto Press (UK) on September 15, 2017.

The crisis of the neoliberal order has resuscitated a political idea widely believed to be consigned to the dustbin of history. Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the neo-nationalist, anti-globalisation and anti-establishment backlash engulfing the West all involve a yearning for a relic of the past: national sovereignty.

In response to these challenging times, economist William Mitchell and political theorist Thomas Fazi reconceptualise the nation state as a vehicle for progressive change. They show how despite the ravages of neoliberalism, the state still contains resources for democratic control of a nation’s economy and finances. The populist turn provides an opening to develop an ambitious but feasible left political strategy. Reclaiming the Nation State offers an urgent, provocative and prescient political analysis of our current predicament, and lays out a comprehensive strategy for revitalising progressive economics in the 21st century.

You can Pre-order the book.

The Paperback is £18.99 and the Hardcover is £67.08. The book is 320 pages.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

When I was younger I wondered why the unemployed didn’t take the opportunity to learn things – a new language, a musical instrument etc – given they now had ‘free’ time.

What a good idea; but how is one going to learn to play a musical instrument, or a new language, when he/she could not afford to buy an instrument or a book and dictionary.

I was born in this time and did not read a proper book until I was 18 years old, when I first could afford to join a Library.

Considering the Greek situation; it is rather different, their citizens may not have a job, but they are wealthier in general than are the Germans or Austrians, because the majority of them own their own houses, where as the latter do not.

Furthermore the work ethic is also rather different. I can speak from experience.

If like me you despise Amazon for their working conditions and treatment of employees, then if ok with Bill, i’d like to add some bookstores with free shipping that are not owned by Amazon:

Europe/UK https://wordery.com/reclaiming-the-state-william-mitchell-9780745337326?cTrk=NTMzMjk2MDV8NTk1MTBhNjljMmQwYjoxOjI6OjY3ODQxNjcz

US https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/reclaiming-the-state-bill-mitchell/1126026034?ean=9780745337326

AU

being without a job might not be near as bad if there was a guaranteed income;

people might not eat their neighbor’s dog if they could still buy food

Before the 2016 election, some graduate student in my lab was discussing voter ID laws with me.

Conservatives want voter ID law because poor blacks can’t get them. Some states in the South have cut so much of their DMV office, they can’t give them ID’s. Richard Nixon started the War on Drugs to jail black people so that they can’t vote Democratic, voter ID is part of the voter suppression program in the united police state of America.

The graduate student was baffled. He asked “why don’t black people just get voter ID’s, it is so simple.”

This study provides an account of the reality: when people become unemployed/stricken with poverty, they become passive and hopeless. Democrats and Republicans have taken turns devastating black communities and not give them employment opportunities.

De-industrialization have also caused many white communities to deteriorate too. Drug addiction has become a huge problem. Dr. Carl Hart, who is a psychologist at Columbia, has said that poverty devastated the community before any drugs did. People don’t usually get addicted to drugs, but when unemployment is high, more people tend to get addicted to drugs–to get some pleasure out of the misery they are in.

All point to one solution: Job Guarantee.

Complaining why black people don’t do this or that doesn’t solve anything. It’s just more of the professional/managerial/privileged/lucky people’s excuses to keep the status quo.

The provision of educational facilities is absolutely essential to provide meeting places and learning opportunities. In the UK in the 80’s much adult education crumbled and largely ceased to be affordable-it seems that neo-liberals like a dumbed-down populace zombified by trashy television.

There are always a small percentage of unemployed people who do manage to use their time well ans still develop themselves if the facilities allow but I suspect this is a fairly small group. I’ve been unemployed and don’t work now due to health issues and I often tell people how much harder NOT working is than working and how challenging it can be to create meaning and purpose and order your day and keep motivated.

Ali Velshi is an economic guru for MSNBC in the US…but posting this was prompted by Bill’s the “future of work in a capitalist society”…..sorry a bit wordy but clearly relevant to the subject, agree or disagree–two cents from this side of the pond….

FACEBOOK POST: Ali Velshi…. You are exactly on target on the Republican tax cut pretending to be healthcare-but curious re JOBS…..i.e., during the meltdown….2008-9-on CNN’s Your Money, you referred to “public-sector” jobs the same as one would speak of having leprosy-but I am curious if-considering how flat our economy has been in the interim-if you have changed your position? The following hopefully clarifies the question:

President Trump/Council of Economic Advisors:

RE: GPS Fareed Zakaria, 6/25/17

The fact is, we have far more work that needs to be done in America, than persons to fill these jobs, and when we get serious about addressing the etiology for the ISIS radical, etc., the following is a solution: Pro-Market, deficit-neutral THE NEIGHBOR-TO-NEIGHBOR JOB CREATION ACT [hereafter NTN, Amazon]:

A federally-mandated Social Insurance [a condition of employment], to provide a fund to hire/train our unemployed, triggered by Public Law 15 USC § 3101-i.e., restricting our UE rate to 3%–permanently. Jobs beget jobs, and for a modest 4% of salary policy cost NTN will create more “private-sector” jobs in 6 months, than HR 2847 [the HIRE Act] in 6 years.

The evidence is over-whelming that the market cannot provide everybody wanting a job, with a job-and yet, this has been our sole model for Job Creation in America-and to this day–since WW II!

Indeed, this model has not resulted in an unemployment [hereafter UE] rate below 3% since 1953! Leaving millions jobless in its wake, resulting in an epidemic of gun violence in our inner-cities! And given automation [robots], alone, the problem is infinitely magnified the further we advance into the 21st Century.

The principle at issue, here, is transparent: the doctor can’t perform the operation without the proper instruments-nor can the mechanic work without the proper tools–and with the NUMBER ONE issue in every election-and with growing intensity since 1980-for JOBS, JOBS, JOBS-it is obvious we are not using the proper tool to solve this vital social problem!

It would be ideal if the market could provide everybody with a job-but the evidence is over-whelming that it can’t! We also can’t solve the number one issue facing America by cutting taxes for the 1% when this has twice cost Americans millions of jobs [1987 & 2008]!

The bottom line is: UE is a NO ONE WINS! The jobless lose, civility loses [Ferguson, etc.], and THE MARKET loses, to wit:

THE LAW OF DIMINISHED INCOME TO THE MARKET FROM UNEMPLOYMENT [hereafter D/UE LAW]

Short Definition:

3% is the zero-sum threshold above which unemployment starts substantially undermining the Market–and the loss in income to the Market is compounded exponentially with each percentage point of increase in unemployment, above 3%. [See also HR 1000].

Jim Green, Candidate for Congress, 2000

Thank you for contacting the White House.

“Workers deprived of the capacity to gain employment are simultaneously deprived of social interactions that are important in creating aspiration and hope.”

Exactly my experience. Personally, I thought unemployment would allow me to pursue fulfilling activities, I could learn to play more instruments, read literature etc…and eventually I’d find work.

After several months I began to lose hope that I’d ever be able to take part and be able to afford to be a part of society. I become distant and leaving the house became a challenge. A simple walk to the shops required half a day to motivate myself. It wasn’t just the lost income, but a loss of self-identity. I’ve seen similar things with friends and family. To work towards seeking employment is wrought with anxiety, each rejection reinforces a hopeless feeling and you become disinterested in life. It is barely existing and certainly not living.

I thought further study would be a good option, certainly without support, this became impossible. It wasn’t until I found secure part time work (organised through a family member) that allowed me to develop a better sense of self and a purpose, that I could then work towards goals and I began to feel fulfilled in the activities I participated in. It took two solid years of work to build myself up to a state I felt comfortable and felt belonging and purpose.

Then work definitely needs to be secure and your income needs to allow you to participate in society and provide shelter! Despite work being beneficial to a sense of self, it didn’t help that my savings (four times the average for my age group) was insufficient to put down a deposit of my own independent space. A goal certainly most people have. Housing seems exclusively for the wealthy in Australia, with that comes high debt levels! Though our society place an immense pressure to purchase housing as investment, I’m pleased to say I resisted (I never had a 20% deposit yet the bank would loan me money with insurance of course) and saw the Australian housing market for the ponzi scheme it is.

Working now as a full time casual teacher for a small (dodgy) private college, public holidays become punishment and holiday breaks equal lost earnings. No loading or compensation can make up for job insecurity and not knowing if you have work next term.

It’s extraordinarily depressing knowing that the current system of private vocational colleges (Australia) is there as a way to deliver more profit to capital and staff are required to work more for less. My job literally has me teaching a course that doesn’t exist, no goals, no measurable outcomes and an unwillingness for my employer to pay plan and develop a course!

“For example, mass unemployment is a vehicle for class domination – capital over labour. It is no surprise that neo-liberal governments use mass unemployment to entrench their own hegemony”

mass unemployment isn’t an option for neo liberal governments these days , and eventually neither is supressing the wage rate.

in this country we have what 25 seats that determine the election , a fair whack of them mortgage belt seats with heavily indebted households requiring atleast 1.5 incomes to service the debt.

the unemployment rate starts ticking over 7% or wages growth stalls and the neo liberals go into electoral oblivion and the banks wont be too far behind them .

every crisis , brings an ever greater need for government and central bank balance sheet expansion , and eventually if it isn’t already , government money is going to be the hedge against economic collapse, and these current attempts to reverse the tide will prove futile.

we will all be very high tech socialists in the end 😉

“The question is whether the findings of such a study remain relevant today. Have societies and values changed to render these observations irrelevant.

The contention in our book is that no such metamorphosis has taken place. Work is still a central aspect of our lives and value systems”

just because the metamorphosis hasn’t taken place yet , doesn’t mean it isn’t going to happen. human beings are going to invent a bewildering array of technologies that is going to make this debate redundant and then we will also get rid of the currency system as well.

I mean why work , when you can be a perpetual student , admire the occasional statue , throw great parties and every day is a holiday.

my robot butler had better know how to make lasagne.

the law of least effort.

“…human beings are going to invent a bewildering array of technologies that is going to make this debate redundant and then we will also get rid of the currency system as well.”

Well here’s a sentence that needs so much unpacking or so many caveats that it is barely meaningful.

Anyway here’s another random assertion…the sentence above and what it refers to…

ain’t gonna happen.

@philjomar,

well is moores law , big data , AI , robotics, and zero recurrent cost energy or nearly free energy , going to lead to large gains in productivity where humans wont be involved in the gains or not.

these aren’t just the imaginings of futurists these days.

to me the major productivity gains are still ahead of us not behind us, and within 500 years a human being might only need to work 5 years not 40 to meet societies needs.

so what do we do with the other 100 years of our lives.

a major discontinuity like a major war or two might slow the process down , but all that means is the time frame gets blown out, not the big picture.

There is an English language edition of the study with some extras — Marienthal: The Sociography of an Unemployed Community by Marie Jahoda, Paul F. Lazarsfeld, and Hans Zeisel, with an introduction by Christian Fleck, 7 April 2002 (176 pages). It can be obtained from Amazon.

Oops. I missed Bill’s mention of the English language version. I, too, disapprove of Amazon’s treatment of its workers. In the UK, in addition to Wordery, there is the Book Depository, too. Thanks to Willem for bringing up the subject.

Dear Larry (at 2017/07/11 at 6:12 pm)

The Book Depository is owned by Amazon, Inc. Sorry to disappoint.

best wishes

bill

So am I, Bill. But thanks for the update. Much appreciated.

No wonder the Austrian working class later turned to the hard right when they offered massive spending on public works, great propaganda, fiscal stimulus and later rearmament which all created what the working class craved the most – a job. Hitler’s attacks on the greedy banks and capitalist speculators was hard to disagree with given the pain of the Great Depression. ‘Minor details’ like the butchering of minorities, totalitarianism and world war spoiled the party a little.

Nearly all the world’s progressive parties apparently still feel the need to grovel to the feudal sociopaths that currently decide macroeconomic policy or otherwise they apparently won’t be given permission to win government. The electorates in general remain ignorant, passive or selfish and keep voting for more of this farce. Purge the progressive parties of the neoliberal sociopaths and offer a CREDIBLE CHOICE or await the brutal and short life of the serf or soldier.