At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 79

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

Part III – Options for Europe

Chapter 23 Abandon the Euro Costs, threats and opportunities

[PREVIOUS MATERIAL HERE]

[BY WAY OF EXPLANATION – I AM WRITING SECTIONS OF THIS CHAPTER AS I GET INFORMATION SORTED IN A COHERENT WAY – IN THE FINAL DRAFT – THE SECTIONS MIGHT BE ARRANGED IN A DIFFERENT ORDER TO WHAT WILL APPEAR HERE OVER THE NEXT FEW DAYS. I WROTE MUCH MORE TODAY THAN APPEARS BELOW – BUT THE TEXT BELONGS IN SEVERAL SUB-SECTIONS AND SO I THOUGHT IT WOULD BE LESS DISJOINTED FOR THOSE THAT ENJOY FOLLOWING THE UNFOLDING STORY IF I JUST KEPT WHOLE SUB-SECTIONS TOGETHER.]

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

Why the need for secrecy?

At first blush, the notion that all decision-making and planning associated with the exit would be done in secrecy to minimise the costs of the resulting exit is at odds with the idea of participatory democracy. On the surface, this unilateralism would appear to be similar in effect to the way the Troika has imposed harsh austerity measures on nations and influenced the appointment of senior government officials (for example, the way Lucas Papademos was installed as Prime Minister of Greece in 2011). The problem is that policy surprises are necessary at times if the cost of total transparency are high. It is clear that the transition costs that individuals and business firms would incur as a result of an exit would be not insignificant. The prospect of the likely losses from a depreciated currency would instigate efforts by household and firms to hoard euros or transfer euro deposits to banks and other institutions elsewhere in Europe or swap for other more stable currencies. Secrecy is required to minimise the losses rather than to compromise democracy. There is a temporal perspective that should not be forgotten. The restoration of the national currency makes the elected government fully responsible for national economic and social policy. With regular electoral cycles, citizens are in a much better position to relate outcomes with responsibility.

Lex Monetae – Re-denomination

Lex Monetae or ‘The Law of the Money’ is a well-established legal principle, backed up by a swathe of case law across many jurisdictions, and internationally accepted. It states broadly that the government of the day determines what the legal currency is for transactions and contractual obligations within its national borders. There is thus no question that a nation currently using the euro could abandon it, introduce its own currency, and require all taxes to be paid and all contracts to be denominated in that currency. In Chapter 18 it was explained why the imposition of taxes in a specific currency gives rise to a demand for that currency by non-government entities (households and firms). These entities have to acquire the new currency or be in violation of the tax laws and the only way they can get it is if the government spends it into existence, which defines a basic responsibility of a sovereign government. Lex Monetae also has been taken to mean that if an Italian had borrowed US dollars from an London bank operating under English law, the definition of the ‘currency’ for the purposes of resolving this contract is governed by US law. Finally, the principle also means that if a government changes its currency and re-denomiates at some given parity, all contracts must be honoured at the re-dominated rate.

The euro nations have practical experience with the sort of legislation that would be required for re-denomination having performed the same feat less than 15 years ago. They already understand the processes required and the scope involved. They understand that people might get stuck in car parks and vending machines would need to be recalibrated, among the myriad of conversions that would be required.

At what rate should the re-denomination be made? If the currency is to float, then it doesn’t matter much what the conversion rate is to be initially. The foreign exchange markets will sort out the levels quickly enough. Scott (2012) argues against a float, suggesting instead that the nation should immediately join the ERM and peg against the euro, with massive support from foreign central banks (swap arrangements) to ensure it can defend the currency. Any such arrangement should be avoided by the nation in question. Floating will give the domestic policy instruments (fiscal and monetary) maximum scope as was explained in Chapter 19. However, the possibility of so-called ’rounding up’ problem where converted prices are pushed up to the next finite currency unit does suggest some thought needs to be given to the parity (Capital Economics, 2012).

Financial markets commentator Edward Harrison suggest that the new currency would be pegged against the euro at the December 31, 2001 parity. The European Council Regulation No 2866/98 effective from December 31, 1998 established the conversion rates between the euro and the currencies of the Member States which would adopt the euro. It was amended by Regulation No 1478/2000 of June 19, 2000 to allow for the fact that Greece had ‘satisfied’ the conditions for entry and would adopt the euro from January 1, 2002. Table 23.X shows the so-called ‘irrevocably fixed euro conversion rates’.

Table 23.X Irrevocably fixed euro conversion rates

| 1 euro | = 40,3399 Belgian francs |

| = 1,95583 German marks | |

| = 166,386 Spanish pesetas | |

| = 6,55957 French francs | |

| = 0,787564 Irish pounds | |

| = 1 936,27 Italian lire | |

| = 40,3399 Luxembourg francs | |

| = 2,20371 Dutch guilders | |

| = 13,7603 Austrian schillings | |

| = 200,482 Portuguese escudos | |

| = 5,94573 Finnish marks | |

| = 340.750 Greek drachmas |

Source: European Council, Official Journal L 359 , 31/12/1998 P. 0001 – 0002

Rounding up, unless declared illegal, would be more likely in this case. Others have argued that to avoid the rounding problem, a 1-for-1 parity against the euro be adopted (Capital Economics, 2012: 29).

The complication in the case of the euro is that the Lex Monetae principle becomes blurred or dual in nature because one could argue that the euro persists even if a nation exits and introduces a new currency. Capital Economics (2012: 26) summarises the problem – “it may be uncertain whether any reference to the ‘euro’ should be interpreted as meaning the national currency of Greece at the time that payment is due, and hence as the new drachma, or as the common international currency of the EU as a whole, in which case it would remain the euro.” The complication is likely to apply more to private contracts than the public debt, which typically recognises that a government issues liabilities in the currency it uses. The exception is that the Troika forced the Greek government to issue liabilities under English law in order to gain further bailout assistance, thus anticipating the application of Lex Monetae, in the case of an exit. We do not explore the deeper legal issues in this book. No doubt complex legal cases would drag out for years should the parties decide to take the ‘costly’ rather than practical option.

Notwithstanding that act of bastardry, the discussion suggests that all public debt would be re-demoninated into the local currency at the going parity on day one. Capital Economics (2012: 26) noted that the “government could also legislate to redenominate all private sector debt governed by local law from euros to the new domestic currency” but considered this should might be confined to financial sector debt “to reduce the risk of a banking sector collapse” (p.26). The crucial issue is what will happen to private sector debt, if the local currency becomes the unit in which wages are paid, prices are set and tax obligations are relinquished? We will return to that issue presently after establishing the general principle that it is better to re-denominate than default, even if the creditors would consider the two to be equivalent.

Re-denomination rather than default?

On June 6, 2011, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble wrote a letter to the ECB, the IMF and his Ecofin finance ministers, which expressed doubt that Greece could meet the terms of the bailout conditions in place and return “to the

capital markets within 2012” (Reuters, 2011). He knew the IMF would not oppose further funding in these circumstances but predicted that without “another disbursement of funds before mid-July, we face the real risk fo the first unorderly default within the euro zone”. He then judged that “any additional financial support for Greece has to involve a fair burden sharing between taxpayers and private investors”, which introduced the idea of the PSI (private sector involvement) at the highest levels. He called for a “substantial contribution of bondholders to the support effort”, which should be achieved ” through a bond swap leading to a prolongation of the outstanding Greek sovereign bonds by seven years” (Reuters, 2011). This set in place what would become a major default by the Greek government on its privately-held debt liabilities all managed by the Troika.

The Greek government bond debt held by the ECB (its largest creditor), the national central banks (also large creditors) and the European Investment Bank (a smaller creditor) were excluded from the haircut. Various tricky legal mechanisms were put in place to ensure the default was not subject to further legal challenges (for example, to cope with debt issued under English law). The details of the PSI need not concern us here but suffice to say, the “present value of the haircut of the Greek debt exchange was in the range of 59-65 percent” (Zettelmeyer, 2013: 19). The question is why is a forced restructuring of public debt to the detriment of the investor preferable to a negotiated withdrawal? The PSI was a Troika-managed and imposed loss for private investors who had presumably acted in good faith.

In the case of the withdrawal the losses would come via the re-denomination of the debt and the likely depreciation of the new currency. Scott (201z: 3) argues, however, that “redenomination of debt has distinct advantages over restructuring as a technique to reduce debt burden”.

[TO BE CONTINUED INCLUDING A COMPARISON WITH THE SCHEME WERE NO RE-DOMINATION IS DONE]

Inflation threat from depreciation

It is often argued that the “key danger for countries departing the euro is hyperinflation due to poor fiscal and monetary policies” (Tepper, 2012: 136). Most of the commentary surrounding the risk of hyperinflation following an exit concentrates on scenarios where the government is unable to access private debt markets as a result of a depreciating currency (and other stability concerns) and instead, enters the ‘taboo’ world of central bank deficit funding. We dealt with the myths surrounding this ‘taboo’ in the last chapter. Tepper (2012: 136), like many commentators, dodges around after introducing the ‘taboo’ by claiming that “potentially generating hyperinflation” was a risk of such a policy stance. We emphasise “potentially”, which is in the same class of scaremongering as ‘might’ and ‘may’. We have already learned that any increase in spending, whether it be private or public, carries a risk of inflation if it pushes the economy beyond its capacity to respond by increasing the production and sales of goods and services. For nations mired in recession with large quantities of idle resources, it is highly unlikely that increased deficits will invoke a major inflationary spiral. That situation certainly describes the state of many European nations in the aftermath of the GFC and the imposed austerity.

The main source of inflation would be the rising prices of imported goods and services in terms of the local currency as a result of the likely (significant) depreciation. History tells us that such depreciations are short and sharp. Argentina is an example. However, more recent ‘European’ experience is available. When Iceland’s financial system collapsed in 2008, the government refused to bailout the private banks and instead restructured domestically-held deposits within newly-nationalised banks, pushing all foreign exposure into the bankruptcy process. The Icelandic disaster was another demonstration of the perils of neo-liberalism. Its banking crisis had its roots in deregulation and privatisation of the banks which saw them expand “their balance sheets many times over between 2004 and 2008” (Central Bank of Iceland, 2010: 7). They were aided by flawed credit rating reviews and consulting reports provided by hired academics which waxed lyrical about the state of the economy. One of those academics was Columbia University’s Frederick Mishkin, who featured in the 2010 movie Inside Job and was paid a considerable sum by the Iceland Chamber of Commerce in 2006 to produce the report ‘Financial Stability in Iceland’. At the same time that Mishkin and his co-author were giving the financial system in Iceland a clean bill of health, the Icelandic banks were engaged in elaborate and not so elaborate growth schemes based on refinancing debt with extra borrowing using “fake capital” (and “illegal market manipulation”) to evade scrutiny and allow them to “enter the big-bank league”. (Wade and Sigurgeirsdottir, 2010). The Inside Job highlighted that the payment for Mishkin’s Iceland Report was not initially disclosed and thus it could have been confused as being independent academic research, which gave it considerably more gravitas. After the crisis broke, Mishkin was caught out changing his CV by renaming the paper ‘Financial Instability in Iceland; and when asked about this in the interview he gave the Inside Job, he stumbled, in a dissembling fashion – and eventually managed to get it out that it must have been a ‘typo’.

Just before the collapse the total bank assets were “around 11 times GDP” (p.8) and a large majority of the banks’ operations were in foreign currencies, which meant the central bank was unable to provide any security as a lender of last resort. International markets started to get the jitters in early 2008 and capital inflow dried up, which led to a weakening of the króna and inflation began to accelerating as a result of rising imported goods including petrol (Central Bank of Iceland, 2008). In early October 2008, “nearly nine-tenths of Iceland’s banking system collapsed in a single week” (Central Bank of Iceland, 2010: 8) and the government stepped in with emergency legislation to save the economy from total collapse. The Central Bank of Iceland notes that as “a share of GDP, the Icelandic banking system is the largest banking system ever to have collapsed” (p.9). The bank collapse exacerbated the currency crisis and the króna depreciated by 50 per cent over 2008 in terms of the euro. This was particularly difficult for Icelandic households who were heavily indebted in foreign currencies and there were “enormous losses of private sector wealth, and a steep drop in disposable income” (p.10). This was compounded by the “because of widespread inflation-indexed debt” (p.10).

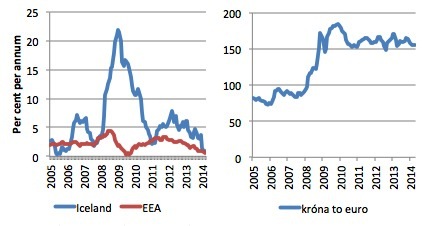

The króna appreciated by close to 10 per cent in the first-half of 2010 and by October 2010, the inflation rate, which had peaked at 21.9 per cent in January 2009 was back down to the central bank’s “4% threshold band” (p.12) (see Figure 24.X). While the IMF became involved under its Standby Arrangements and the government was prevented from introducing a full-scale discretionary fiscal stimulus, the “automatic stabilisers were allowed to work fully in 2009” (p.10), which cushioned the loss of total spending. Moreover, the government, realising it was partially constrained by the IMF program, freed up rules relating to private pension savings and relative to GDP, “the size of the pension withdrawal scheme is broadly similar to fiscal stimulus packages that many other countries adopted in response to the crisis” (p.10). In other words, there was not a blanket austerity imposed on the economy and the spending growth led to the recovery. Figure 24.x charts the evolution of Iceland’s inflation rate and exchange rate from January 2005 to the present day.

Figure 24.X Iceland inflation rate and exchange rate, January 2005-May 2014

Source: Statistics Iceland, Central Bank of Iceland. Exchange rate is the monthly average. The European Economic Area (EEA) comprises three member states of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway).

It is crucial that the exiting government puts in place processes to ensure that the nominal exchange rate depreciation leads to a real depreciation. The real income loss arising from the rising import prices is one of the costs of exit and the government should ensure that the burden is equitably shared. Thus, if domestic wages and prices are fully compensated for the rise in import prices following a depreciation, then the nation would not enjoy any competitive gain. It is clear that real standards of living have to fall in terms of traded goods for the nominal depreciation to ‘stick’. It is politically easier to engineer a real depreciation via a nominal exchange rate decline than it is to undertake so-called ‘internal depreciation’, which involves cutting the money wages that workers receive. Keynes long ago argued that there were very good reasons for why workers resist nominal wage cuts. First, wages are not only an indicator of earnings potential but also a social index. People think in relative terms as much as they consider absolutes, which means our place in the wage structure is important to us.

We know that if inflation outstrips the growth in money wages then our purchasing power (our real wages) will fall, but our relative position in the wage structure will not be threatened because the real wage cut is across the board. However, if one group of workers takes a money wage cut then that alters their relative position and it is unlikely that the relative loss will be made up when the economy recovers. So there is little incentive to accept nominal wage cuts even if they deliver the same real wage cut as a generalised inflation or an exchange rate depreciation might. Second, our most important contracts are in nominal rather than real terms. When we take out a mortgage at the bank we rarely have indexed contracts. Most of us are obligated to pay a certain number of dollars per month to service the debt. Nominal income cuts thus may impact on our solvency – that is, our absolute capacity to service our nominal contractual obligationss. While a decline in real income arising from inflation is difficult to deal with, we are still able, within limits, to alter our consumption mix (for example, reduce discretionary entertainment, dining out etc) and still maintain our solvency with respect to our nominal contractual obligations. This feature of wage rigidity, while criticised by mainstream economists, is, in fact, a source of stability in the economy. It prevents widespread bankruptcies from occurring and the associated fall out that follows. Firms also resist cutting wages because they do not want to be seen as a capricious employer. They know that when times are good they would find it hard attracting labour if they had behaved badly in the downturn when their bargaining power was increased.

There are thus solid reasons why it is difficult for economies to cut nominal wages during a downturn. Further, even if an across the board cut in money wage levels could be accomplished, the problem then is that unit costs will also fall. Competition for market share between firms is then likely to lead to price cuts, which means that the purchasing power equivalent of the wages (the so-called real wage) might not fall much if at all. In this case, no gains in competition will occur. The point is that the real wage is not a variable that an individual unemployed worker can manipulate to their own advantage anyway. Moreover, reducing real wages and profits by ‘internal depreciation’ is likely to undermine total spending in the economy and make the downturn worse as people reduce their consumption and firms constrain their investment spending in the face of falling sales and rising unemployment. But if the same fall in real living standards is accomplished via an exchange rate depreciation, the economy will experience an increased capacity to export due to the rise in international competitiveness, which may reduce or even offset the decline in domestic demand. The decline in domestic demand can also be made up with fiscal policy stimulus.

Proponents of the ‘internal devaluation’ path cite Latvia as an example. Between 2008 and 2010, Latvia’s monthly labour costs fell by a staggering 34.4 per cent in total (public sector by 30 per cent and private sector by 37.3 per cent) (Latvijas Statistika, Table DIG02, Annual Labour Costs and Their Structure). This signifies a very large internal deflation. Over the same period, the employment to population ratio fell from 68.1 per cent to 58.5 per cent and the unemployment rate rose from 4.5 per cent in 2007 to 14.5 per cent in 2010. In 2013, Latvia’s unemployment rate (9 per cent) remained at double its 2007 value and would have been much worse had there not been the staggering 9.2 per cent decline in the population since 2007 (Latvijas Statistika data) as a result of massive out-migration of citizens searching for employment elsewhere. In 2010, net out-migration was running around 36 thousand people per month. The decline in real GDP between 2007 and 2010 was around 21 per cent and by 2013, the economy was about 9 per cent smaller than it was in 2007. Its recent growth up to 2013 has not been due to a major surge in exports. Gross capital formation (investment) remained negative in 2013. The modest growth has been supported mainly private and public consumption combined with declining imports. It is hardly a testament for the benefits of ‘internal deflation’.

Would the nation need to impose capital controls?

Would the nation need to impose capital controls? Some commentators claim that an exit would instantly destroy the Greek banking system (for example, Buiter, 2011). It is a moot point whether the European banking system, particularly in nations such as Ireland or Greece is actually solvent. But that point aside, capital controls are policies that place restrictions on the free movement of capital in or out of a nation. Like Overt Monetary Financing, capital controls are another one of those ‘taboo’ topics for mainstream economists. They hate the idea of anything that interferes with the so-called rational market. The reason nations impose controls, despite traditional opposition from multilateral agencies such as the IMF, is that the financial markets are, in fact, highly irrational, and nothing like the way the economics textbooks would like us to think of them. Despite the claims to the contrary, governments impose such controls because they are largely effective, if they are designed and implemented carefully. There are many types of controls ranging from outright prohibitions to market-based incentives, which increase the cost of cross-border transactions (see Ariyoshi et al, 2000). In the context of a nation exiting the EMU, capital controls could limit the extent of the currency depreciation. If targetted to short-term capital transactions they could also serve “to counter speculative flows that threaten to undermine the stability of the exchange rate and deplete foreign exchange reserves” (Ariyoshi et al, 2000: 18). In short, they allow a nation to “buy time” (p.18).

There are many other examples where such policies can reduce foreign exchange market pressures. While the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Monetary Union in 1919 also provides some insights into the strategies that a government can employ to avoid bank runs (‘overstamping’ existing banknotes; forced loans to government; restrictions on travel) one should not take the analogy too far. The capacity to make electronic transfers now means that people do not have to get on intercontinental trains with suitcases full of banknotes to protect themselves from currency depreciation (see Eichengreen, 2010). More recent examples demonstrate, however, that capital controls can be effective. Malaysia imposed a range of controls on capital outflows during the 1997-99 Asian financial crisis, which “helped to stabilize the exchange rate” (p.24). When the Czech and Slovak governments decided to abandon their short-lived monetary union in early 1993, cross-border currency movements were prohibited while new Slovak banknotes were issued. The old Czech banknotes were ‘stamped’ and were in use in Slovakia until August 1993. Capital controls were very effective in protecting the Slovak banking system. More recently, Iceland also imposed capital controls in 2008 which limited the extent of the depreciation of the currency.

While mainstream economists claim that such controls will always be subverted by the financial markets, development economist Dani Rodrik adopts a more realistic assessment:

Even if true, evading the controls requires incurring additional costs to move funds in and out of a country – which is precisely what the controls aim to achieve. Otherwise, why would investors and speculators cry bloody murder whenever capital controls are mentioned as a possibility? If they really couldn’t care less, then they shouldn’t care at all.

Without any cross-border restrictions on financial flows, households and firms in a nation abandoning the EMU may seek to relocate their euro deposits and other financial assets to other euro-zone nations or even into another currency altogether. The exiting government could employ a range of measures (for example, freeze bank withdrawals; restrict electronic transfers etc) to prevent runs on the banks. While it is likely that there has already been substantial cross-border movements in deposits and other financial assets in nations such as Greece, the fact remains that there are still substantial deposit remaining in the Greek banking system. Data from the Central Bank of Greece shows that deposits in Greek banks by domestic residents peaked at 246,210 million euros in September 2009 and then fell steadily to a low of 158,580 million euros by June 2012. They have subsequently risen 177,203 million euros by March 2014. The decline in deposits was mainly due to reductions in household savings as a result of the depression. The deposits held in Greek banks by ‘other euro area residents’ have not significantly declined.

The imposition of capital controls should be seen as part of a broader agenda of bank reform once the exit is consolidated. Local banks should play no role in facilitating the entry of speculative short-term flows. The only useful thing a bank should do is to faciliate a payments system and provide loans to credit-worthy customers. First, they should only be permitted to lend directly to borrowers. All loans would have to be shown and kept on their balance sheets. This would stop all third-party commission deals which might involve banks acting as ‘brokers’ and on-selling loans or other financial assets for profit. It is in this area of banking that the current financial crisis has emerged and it is costly and difficult to regulate. Banks should go back to being what they were. Second, banks should not be allowed to accept any financial asset as collateral to support loans. The collateral should be the estimated value of the income stream on the asset for which the loan is being advanced. This will force banks to appraise the credit risk more fully. Third, banks should be prevented from having ‘off-balance sheet’ assets, such as finance company arms which can evade regulation. Fourth, banks should never be allowed to trade in credit default insurance. This is related to whom should price risk. Fifth, banks should be restricted to the facilitation of loans and not engage in any other commercial activity.

It is unlikely that the banking union reforms that are slowly working their way through the tortured European processes will go anywhere near to introducing these fundamental changes. A nation with its own currency restored and its own central bank and prudential law will be better able to restructure its banking system.

[CONTINUE TOMORROW – OUTLINING ALL THE STEPS AND ISSUES INVOLVED IN A UNILATERAL EXIT]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments