A balanced budget amendment in the US would ensure that the private sector debt levels would rise in the current circumstances.

Answer: True

The answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances - the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance - that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent - given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I - S) + (X - M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

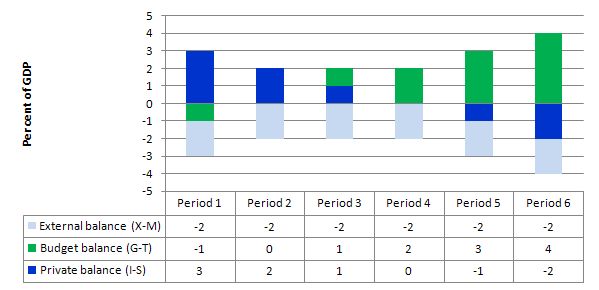

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP (which is artificial because as economic activity changes imports also rise and fall).

The assumption of an external deficit relates to the reality that the US economy is unlikely to deliver an external surplus anytime soon. So the external deficit is what I meant by "in the current circumstances">

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If we assume these Periods are average positions over the course of each business cycle (that is, Period 1 is a separate business cycle to Period 2 etc).

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), a budget surplus of 1 per cent of GDP and the private sector is in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

In Period 2, as the government budget enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit. This is the case that the question is referring to.

This provides another important rule with the deficit terorists typically overlook - that if a nation records an average external deficit over the course of the business cycle (peak to peak) and you succeed in balancing the public budget then the private domestic sector will be in deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt to fund its "excess expenditure". That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a budget with an external deficit. It could never be a viable fiscal rule.

In Periods 3 and 4, the budget deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of budget deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

So what is the economics that underpin these different situations?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative - that is net drain of spending - dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is "earning" and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

So if the G is spending less than it is "earning" and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government budget deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Question 5 - Premium question

In Year 1, the economy plunges into recession with nominal GDP growth falling to minus -1 per cent. The inflation rate is subdued at 1 per cent per annum. The outstanding public debt is equal to the value of the nominal GDP and the nominal interest rate is equal to 1 per cent (and this is the rate the government pays on all outstanding debt). The government's budget balance net of interest payments goes into deficit equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP and the debt ratio rises by 3 per cent. In Year 2, the government stimulates the economy and pushes the primary budget deficit out to 2 per cent of GDP and in doing so stimulates aggregate demand and the economy records a 4 per cent nominal GDP growth rate. All other parameters are unchanged in Year 2. Under these circumstances, the public debt ratio will fall because of the real growth in the economy.

The answer is True.

This question requires you to understand the key parameters and relationships that determine the dynamics of the public debt ratio. An understanding of these relationships allows you to debunk statements that are made by those who think fiscal austerity will allow a government to reduce its public debt ratio.

While Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue, the mainstream debate is dominated by the concept.

The unnecessary practice of fiat currency-issuing governments of issuing public debt $-for-$ to match public net spending (deficits) ensures that the debt levels will rise when there are deficits.

Rising deficits usually mean declining economic activity (especially if there is no evidence of accelerating inflation) which suggests that the debt/GDP ratio may be rising because the denominator is also likely to be falling or rising below trend.

Further, historical experience tells us that when economic growth resumes after a major recession, during which the public debt ratio can rise sharply, the latter always declines again.

It is this endogenous nature of the ratio that suggests it is far more important to focus on the underlying economic problems which the public debt ratio just mirrors.

Mainstream economics starts with the flawed analogy between the household and the sovereign government such that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts has to be "financed" in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and/or (b) by "printing money".

Neither characterisation is remotely representative of what happens in the real world in terms of the operations that define transactions between the government and non-government sector.

Further, the basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.

However, in mainstream framework for analysing these so-called "financing" choices - the so-called government budget constraint (GBC) - it is stated that the budget deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt over year t plus the change in high powered money over year t. So in mathematical terms it is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments - Tax receipts must equal (be "financed" by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

However, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So in terms of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

But for the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

Further, in mainstream economics, money creation is erroneously depicted as the government asking the central bank to buy treasury bonds which the central bank in return then prints money. The government then spends this money.

This is called debt monetisation and you can find out why this is typically not a viable option for a central bank by reading the Deficits 101 suite - Deficit spending 101 - Part 1 - Deficit spending 101 - Part 2 - Deficit spending 101 - Part 3.

The mainstream theory claims that if governments increase the money growth rate (they erroneously call this "printing money") the extra spending will cause accelerating inflation because there will be "too much money chasing too few goods"! Of-course, we know that proposition to be generally preposterous because economies that are constrained by deficient demand (defined as demand below the full employment level) respond to nominal demand increases by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.

So when governments are expanding deficits to offset a collapse in private spending, there is plenty of spare capacity available to ensure output rather than inflation increases.

But not to be daunted by the "facts", the mainstream claim that because inflation is inevitable if "printing money" occurs, it is unwise to use this option to "finance" net public spending.

Hence they say as a better (but still poor) solution, governments should use debt issuance to "finance" their deficits. Thy also claim this is a poor option because in the short-term it is alleged to increase interest rates and in the longer-term is results in higher future tax rates because the debt has to be "paid back".

Neither proposition bears scrutiny - you can read these blogs - Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? - for further discussion on these points.

The mainstream textbooks are full of elaborate models of debt pay-back, debt stabilisation etc which all claim (falsely) to "prove" that the legacy of past deficits is higher debt and to stabilise the debt, the government must eliminate the deficit which means it must then run a primary surplus equal to interest payments on the existing debt.

A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

The standard mainstream framework, which even the so-called progressives (deficit-doves) use, focuses on the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. The following equation captures the approach:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the real GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate. Real GDP is the nominal GDP deflated by the inflation rate. So the real GDP growth rate is equal to the Nominal GDP growth minus the inflation rate.

This standard mainstream framework is used to highlight the dangers of running deficits. But even progressives (not me) use it in a perverse way to justify deficits in a downturn balanced by surpluses in the upturn.

MMT does not tell us that a currency-issuing government running a deficit can never reduce the debt ratio. The standard formula above can easily demonstrate that a nation running a primary deficit can reduce its public debt ratio over time.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

Here is why that is the case.

A growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant or falling. From the formula above, if the primary budget balance is zero, public debt increases at a rate r but the public debt ratio increases at r - g.

The following Table simulates the two years in question. To make matters simple, assume a public debt ratio at the start of the Year 1 of 100 per cent (so B/Y(-1) = 1) which is equivalent to the statement that "outstanding public debt is equal to the value of the nominal GDP".

Also the nominal interest rate is 1 per cent and the inflation rate is 1 per cent then the current real interest rate (r) is 0 per cent.

If the nominal GDP is growing at -1 per cent and there is an inflation rate of 1 per cent then real GDP is growing (g) at minus 2 per cent.

Under these conditions, the primary budget surplus would have to be equal to 2 per cent of GDP to stabilise the debt ratio (check it for yourself). So, the question suggests the primary budget deficit is actually 1 per cent of GDP we know by computation that the public debt ratio rises by 3 per cent.

The calculation (using the formula in the Table) is:

Change in B/Y = (0 - (-2))*1 + 1 = 3 per cent.

The data in Year 2 is given in the last column in the Table below. Note the public debt ratio has risen to 1.03 because of the rise from last year. You are told that the budget deficit doubles as per cent of GDP (to 2 per cent) and nominal GDP growth shoots up to 4 per cent which means real GDP growth (given the inflation rate) is equal to 3 per cent.

The corresponding calculation for the change in the public debt ratio is:

Change in B/Y = (0 - 3)*1.03 + 2 = -1.1 per cent.

So the growth in the economy is strong enough to reduce the public debt ratio even though the primary budget deficit has doubled.

It is a highly stylised example truncated into a two-period adjustment to demonstrate the point. In the real world, if the budget deficit is a large percentage of GDP then it might take some years to start reducing the public debt ratio as GDP growth ensures.

So even with an increasing (or unchanged) deficit, real GDP growth can reduce the public debt ratio, which is what has happened many times in past history following economic slowdowns.

But the best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn't have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.

The discussion also demonstrates why tightening monetary policy makes it harder for the government to reduce the public debt ratio - which, of-course, is one of the more subtle mainstream ways to force the government to run surpluses.