Fiscal rules such as are embodied in the Stability and Growth Pact of the EMU will continually create conditions of slower growth because they deprive the government of fiscal flexibility to support aggregate demand when necessary.

Answer: False

The answer is False.

One word in the question renders this proposition false. I had originally worded the question (following EMU) "will bias the nations to slower growth" etc which is true and I considered that too easy.

The fiscal policy rules that were agreed in the Maastricht Treaty - budget deficits should not exceed 3 per cent of GDP and public debt should not exceed 60 per cent of GDP - clearly constrain EMU governments during periods when private spending (or net exports) are draining aggregate demand.

In those circumstances, if the private spending withdrawal is sufficiently severe, the automatic stabilisers alone will drive the budget deficit above the required limits. Pressure then is immediately placed on the national governments to introduce discretionary fiscal contractions to get the fiscal balance back within the limits.

Further, after an extended recession, the public debt ratios will almost always go beyond the allowable limits which places further pressure on the government to introduce an extended period of austerity to bring the ratio back within the limits. So the bias is towards slower growth overall.

It is also true that the fiscal rules clearly (and by design) "deprive the government of fiscal flexibility to support aggregate demand when necessary". But that wasn't the question. The question was will these rules continually create conditions of slower growth. The answer is no they will not.

Imagine a situation where the nation has very strong net exports adding to aggregate demand which supports steady growth and full employment without any need for the government to approach the Maastricht thresholds. In this case, the fiscal rules are never binding unless something happens to exports.

The following is an example of this sort of nation. It will take a while for you to work through but it provides a good learning environment for understanding the basic expenditure-income model upon with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) builds its monetary insights. You might want to read this blog - Back to basics - aggregate demand drives output - to refresh your understanding of the sectoral balances.

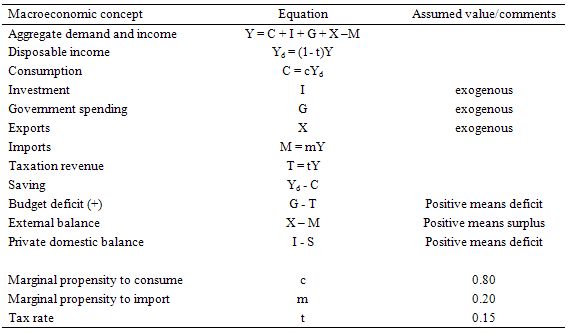

The following Table shows the structure of the simple macroeconomic model that is the foundation of the expenditure-income model. This sort of model is still taught in introductory macroeconomics courses before the students get diverted into the more nonsensical mainstream ideas. All the assumptions with respect to behavioural parameters are very standard. You can download the simple spreadsheet if you want to play around with the model yourselves.

The first Table shows the model structure and any behavioural assumptions used. By way of explanation:

You might want to right-click the images to bring them up into a separate window and the print them (on recycled paper) to make it easier to follow the evolution of this economy over the 10 periods shown.

The next table quantifies the ten-period cycle and the graph below it presents the same information graphically for those who prefer pictures to numbers. The description of events is in between the table and the graph for those who do not want to print.

The graph below shows the sectoral balances - budget deficit (red line), external balance (blue line) and private domestic balance (green line) over the 10-period cycle as a percentage of GDP (Y) in addition to the period-by-period GDP growth (y) in percentage terms (grey bars).

Above the zero line means positive GDP growth, a budget deficit (G > T), an external surplus (X > M) and a private domestic deficit (I > S) and vice-versa for below the zero line.

This is an economy that is enjoying steady GDP growth (1.4 per cent) courtesy of a strong and growing export sector (surpluses in each of the first three periods). It is able to maintain strong growth via the export sector which permits a budget surplus (in each of the first three periods) and the private domestic sector is spending less than they are earning.

The budget parameters (and by implication the public debt ratio) is well within the Maastricht rules and not preventing strong (full employment growth) from occurring. You might say this is a downward bias but from in terms of an understanding of functional finance it just means that the government sector is achieving its goals (full employment) and presumably enough services and public infrastructure while being swamped with tax revenue as a result of the strong export sector.

Then in Period 4, there is a global recession and export markets deteriorate up and governments delay any fiscal stimulus. GDP growth plunges and the private domestic balance moves towards deficit. Total tax revenue falls and the budget deficit moves into balance all due to the automatic stabilisers. There has been no discretionary change in fiscal policy.

In Period 5, we see investment expectations turn sour as a reaction to the declining consumption from Period 4 and the lost export markets. Exports continue to decline and the external balance moves towards deficit (with some offset from the declining imports as a result of lost national income). Together GDP growth falls further and we have a technical recession (two consecutive periods of negative GDP growth).

With unemployment now rising (by implication) the government reacts by increasing government spending and the budget moves into deficit but still within the Maastricht rules. Taxation revenue continues to fall. So the increase in the deficit is partly due to the automatic stabilisers and partly because discretionary fiscal policy is now expanding.

Period 6, exports and investment spending decline further and the government now senses a crisis is on their hands and they accelerate government spending. This starts to reduce the negative GDP growth but pushes the deficit beyond the Maastricht limits of 3 per cent of GDP. Note the rising deficits allows for an improvement in the private domestic balance, although that is also due to the falling investment.

In Period 7, even though exports continue to decline (and the external balance moves into deficit), investors feel more confident given the economy is being supported by growth in the deficit which has arrested the recession. We see a return to positive GDP growth in this period and by implication rising employment, falling unemployment and better times. But the deficit is now well beyond the Maastricht rules and rising even further.

In Period 8, exports decline further but the domestic recovery is well under way supported by the stimulus package and improving investment. We now have an external deficit, rising budget deficit (4.4 per cent of GDP) and rising investment and consumption.

At this point the EMU bosses take over and tell the country that it has to implement an austerity package to get their fiscal parameters back inside the Maastricht rules. So in Period 9, even though investment continues to grow (on past expectations of continued growth in GDP) and the export rout is now stabilised, we see negative GDP growth as government spending is savaged to fit the austerity package agree with the EMU bosses. Net exports moves towards surplus because of the plunge in imports.

Finally, in period 10 the EMU bosses are happy in their warm cosy offices in Brussels or Frankfurt or wherever they have their secure, well-paid jobs because the budget deficit is now back inside the Maastricht rules (2.9 per cent of GDP). Pity about the economy - it is back in a technical recession (a double-dip).

Investment spending has now declined again courtesy of last period's stimulus withdrawal, consumption is falling, government support of saving is in decline, and we would see employment growth falling and unemployment rising.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: