The private domestic sector will always run a deficit (spend more than they earn) which is exactly equal to the external deficit, if the government balances its budget on average over the business cycle.

Answer: True

The answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances - the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance - that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent - given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I - S) + (X - M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

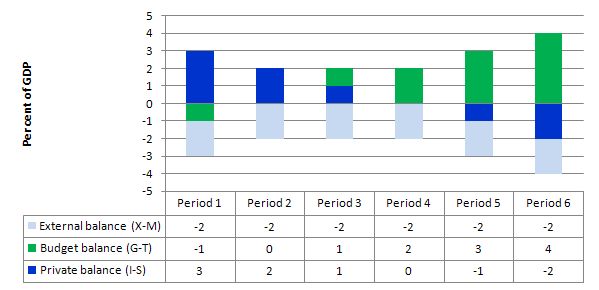

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP (which is artificial because as economic activity changes imports also rise and fall).

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If we assume these Periods are average positions over the course of each business cycle (that is, Period 1 is a separate business cycle to Period 2 etc).

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), a budget surplus of 1 per cent of GDP and the private sector is in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

In Period 2, as the government budget enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit. This is the case that the question is referring to.

This provides another important rule with the deficit terrorists typically overlook - that if a nation records an average external deficit over the course of the business cycle (peak to peak) and you succeed in balancing the public budget then the private domestic sector will be in deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt to fund its "excess expenditure". That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a budget with an external deficit. It could never be a viable fiscal rule.

In Periods 3 and 4, the budget deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of budget deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

So what is the economics that underpin these different situations?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative - that is net drain of spending - dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is "earning" and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

So if the G is spending less than it is "earning" and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government budget deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Question 5 - Premium question:

This is the premium question for this week: Consumption adds to aggregate demand and imports drain aggregate demand. The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is conceptually the extra consumption that is induced for every extra dollar of national income. The marginal propensity to import (MPM) is similarly the extra spending on imports that is induced for every extra dollar of national income. If the MPC and MPM both rise by 0.1 then the impact on aggregate demand for every new dollar of national income generated will be neutral.

The answer is False.

When there is an externally-motivated source of increased aggregate spending (say an injection of government spending or an autonomous increase in private investment), the economy will typically respond by increasing production which generates an equivalent increase in income. This situation relies on their being idle resources than can be brought into the production process and does not apply at full capacity.

So what is spent will generate income in that period which is available for use. The uses are further consumption; paying taxes and/or buying imports. We consider imports as a separate category (even though they reflect consumption, investment and government spending decisions) because they constitute spending which does not recycle back into the production process. They are thus considered to be "leakages" from the expenditure system.

So if for every dollar produced and paid out as income, if the economy imports around 20 cents in the dollar, then only 80 cents is available within the system for spending in subsequent periods excluding taxation considerations. We call this reaction the marginal propensity to import (MPM).

However there are two other "leakages" which arise from domestic sources - saving and taxation. Take taxation first. When income is produced, the households end up with less than they are paid out in gross terms because the government levies a tax. So the income concept available for subsequent spending is called disposable income (Yd).

To keep it simple, imagine a proportional tax of 20 cents in the dollar is levied, so if $100 of income is generated, $20 goes to taxation and Yd is $80 (what is left). So taxation (T) is a "leakage" from the expenditure system in the same way as imports are.

Finally consider saving. Consumers make decisions to spend a proportion of their disposable income. The amount of each dollar they spent at the margin (that is, how much of every extra dollar to they consume) is called the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). If that is 0.80 then they spent 80 cents in every dollar of disposable income.

So if total disposable income is $80 (after taxation of 20 cents in the dollar is collected) then consumption (C) will be 0.80 times $80 which is $64 and saving will be the residual - $26. Saving (S) is also a "leakage" from the expenditure system.

It is easy to see that for every $100 produced, the income that is generated and distributed results in $64 in consumption and $36 in leakages which do not cycle back into spending.

For income to remain at $100 in the next period the $36 has to be made up by what economists call "injections" which in these sorts of models comprise the sum of investment (I), government spending (G) and exports (X). The injections are seen as coming from "outside" the output-income generating process (they are called exogenous or autonomous expenditure variables).

Investment is dependent on expectations of future revenue and costs of borrowing. Government spending is clearly a reflection of policy choices available to government. Exports are determined by world incomes and real exchange rates etc.

For GDP to be stable injections have to equal leakages (this can be converted into growth terms to the same effect). The national accounting statements that we have discussed previous such that the government deficit (surplus) equals $-for-$ the non-government surplus (deficit) and those that decompose the non-government sector in the external and private domestic sectors is derived from these relationships.

So imagine there is a certain level of income being produced - its value is immaterial. Imagine that the central bank sees no inflation risk and so interest rates are stable as are exchange rates (these simplifications are to to eliminate unnecessary complexity).

The question then is: what would happen if government increased spending by, say, $100? In macroeconomics this question is answered by examining what it known as the expenditure multiplier. If aggregate demand increases drive higher output and income increases then the question is by how much?

The expenditure multiplier is defined as the change in real income that results from a dollar change in exogenous aggregate demand (so one of G, I or X). We could complicate this by having autonomous consumption as well but the principle is not altered.

Consumption and Saving

So the starting point is to define the consumption relationship. The most simple is a proportional relationship to disposable income (Yd). So we might write it as C = c*Yd - where little c is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) or the fraction of every dollar of disposable income consumed. We will use c = 0.8.

The * sign denotes multiplication. You can do this example in an spreadsheet if you like.

Taxes

Our tax relationship is already defined above - so T = tY. The little t is the marginal tax rate which in this case is the proportional rate (assume it is 0.2). Note here taxes are taken out of total income (Y) which then defines disposable income.

So Yd = (1-t) times Y or Yd = (1-0.2)*Y = 0.8*Y

Imports

If imports (M) are 20 per cent of total income (Y) then the relationship is M = m*Y where little m is the marginal propensity to import or the economy will increase imports by 20 cents for every real GDP dollar produced.

Multiplier

If you understand all that then the explanation of the multiplier follows logically. Imagine that government spending went up by $100 and the change in real national income is $179. Then the multiplier is the ratio (denoted k) of the

Change in Total Income to the Change in government spending.

Thus k = $179/$100 = 1.79.

This says that for every dollar the government spends total real GDP will rise by $1.79 after taking into account the leakages from taxation, saving and imports.

When we conduct this thought experiment we are assuming the other autonomous expenditure components (I and X) are unchanged.

But the important point is to understand why the process generates a multiplier value of 1.79.

The formula for the spending multiplier is given as:

k = 1/(1 - c*(1-t) + m)

where c is the MPC, t is the tax rate so c(1-t) is the extra spending per dollar of disposable income and m is the MPM. The * denotes multiplication as before.

This formula is derived as follows:

The national income identity outlined in Question 4 is:

GDP = Y = C + I + G + (X - M)

A simple model of these expenditure components taking the information above is:

GDP = Y = c*Yd + I + G + X - m*Y

Yd = (1 - t)*Y

We consider (in this model for simplicity) that the expenditure components I, G and X are autonomous and do not depend on the level of income (GDP) in any particular period. So we can aggregate them as all autonomous expenditure A.

Thus:

GDP = Y = c*(1- t)*Y -m*Y + A

While I am not trying to test one's ability to do algebra, and in that sense the answer can be worked out conceptually, to get the multiplier formula we re-arrange the previous equation as follows:

Y - c*(1-t)*Y + m*Y - A

Then collect the like terms and simplify:

Y[1-c*(1-t) + m] = A

So a change in A will generate a change in Y according to the this formula:

Change in Y = k = 1/(1 -c*(1-t) + m)*Change in A

or if k = 1/(1 -c*(1-t) + m)

Change in Y = k*Change in A.

]

In the current example, the following spreadsheet table explains what is going on in terms of the economics.

So at the start of Period 1, the government increases spending by $100. The Table then traces out the changes that occur in the macroeconomic aggregates that follow this increase in spending (and "injection" of $100). The total change in real GDP (Column 1) will then tell us the multiplier value (although there is a simple formula that can compute it). The parameters which drive the individual flows are shown at the bottom of the table.

Note I have left out the full period adjustment - only showing up to Period 12. After that the adjustments are tiny until they peter out to zero.

Firms initially react to the $100 order from government at the beginning of the process of change. They increase output (assuming no change in inventories) and generate an extra $100 in income as a consequence which is the 100 change in GDP in Column [1].

The government taxes this income increase at 20 cents in the dollar (t = 0.20) and so disposable income only rises by $80 (Column 5).

There is a saying that one person's income is another person's expenditure and so the more the latter spends the more the former will receive and spend in turn - repeating the process.

Households spend 80 cents of every disposable dollar they receive which means that consumption rises by $64 in response to the rise in production/income. Households also save $16 of disposable income as a residual.

Imports also rise by $20 given that every dollar of GDP leads to a 20 cents increase imports (by assumption here) and this spending is lost from the spending stream in the next period.

So the initial rise in government spending has induced new consumption spending of $64. The workers who earned that income spend it and the production system responds. But remember $20 was lost from the spending stream so

the second period spending increase is $44. Firms react and generate and extra $44 to meet the increase in aggregate demand.

And so the process continues with each period seeing a smaller and smaller induced spending effect (via consumption) because the leakages are draining the spending that gets recycled into increased production.

Eventually the process stops and income reaches its new "equilibrium" level in response to the step-increase of $100 in government spending. Note I haven't show the total process in the Table and the final totals are the actual final totals.

If you check the total change in leakages (S + T + M) in Column (6) you see they equal $100 which matches the initial injection of government spending. The rule is that the multiplier process ends when the sum of the change in leakages matches the initial injection which started the process off.

You can also see that the initial injection of government spending ($100) stimulates an eventual rise in GDP of $179 (hence the multiplier of 1.79) and consumption has risen by 114, Saving by 29 and Imports by 36.

In this case the change in the budget position would be (100-36) = $64 which has allowed private saving to rise. The implied current account deficit (with X fixed) would have increased a bit. A full model would introduce exchange rate effects. In this case, the exchange rate would likely fall a little (under the assumption of no change in autonomous X) which would stimulate X and reduce M a bit which would "crowd in" further income growth.

Further, inasmuch some imported inflation occurred (a tiny amount if any) then real interest rates would rise and might further stimulate output via investment. These additional effects are possible but probably fairly small in magnitude.

In general, the multiplier is larger the smaller the leakages. So the lower is the import leakage per dollar and the lower the taxation rate the larger the multiplier and the

The following graph shows you the income and induced consumption adjustment path. The initial injection stimulates a lot of activity which then induces further consumption but in smaller and smaller amounts as the leakages impact in each period.

This type of approach also tells you that if the government was to cut taxes such that the households received the equivalent of $100 in extra disposable income the final multiplier would be lower because households will initially seek to save a proportion of the initial bonus. In other words, the first round injection would be less than the $100 and then the subsequent multiplier rounds would be smaller and the process would exhaust itself more quickly.

Now consider the two situations outlined in the question which are represented in the following Table.

You can see that when the MPC and the MPM both rise by 0.1 the expenditure multiplier falls from 1.79 (given starting values) to 1.72.

The reason? The fall in the MPM increases the drain on aggregate spending for every dollar of new national income by 10 cents. The rise in the MPC by 0.1 increases the induced consumption component by 10 per cent of every dollar of disposable income generated.

Given that the disposable income is less than total income (because of the positive tax rate), the increased import drain on spending is higher than the extra spending coming from the increased consumption and so the overall net impact of an extra dollar of national income falls.

The following blog may be of further interest to you: