In a fiat monetary system (for example, US or Australia) with an on-going external deficit, if you desire the domestic private sector to reduce its overall debt levels without employment losses, then you have to support the national government continually increasing the budget deficit in line with the private de-leveraging process.

Answer: Maybe

The answer is Maybe.

This question is an application of the sectoral balances framework that can be derived from the National Accounts for any nation.

The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

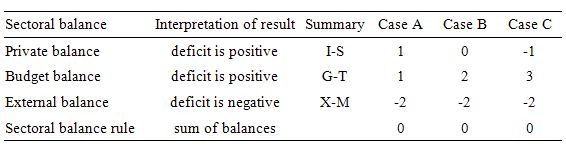

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I - S) + (X - M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

To help us answer the specific question posed, we can identify three states all involving public and external deficits:

The following Table shows these three cases expressing the balances as percentages of GDP. Case A shows the situation where the external deficit exceeds the public deficit and the private domestic sector is in deficit. In this case, there can be no overall private sector de-leveraging.

With the external balance set at a 2 per cent of GDP, as the budget moves into larger deficit, the private domestic balance approaches balance (Case B). Case B also does not permit the private sector to save overall.

Once the budget deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) the private domestic sector can save overall (Case C).

In this situation, the budget deficits are supporting aggregate spending which allows income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector but have to be able to offset the demand-draining impacts of the external deficits to provide sufficient income growth for the private domestic sector to save.

For the domestic private sector (households and firms) to reduce their overall levels of debt they have to net save overall. The behavioural implications of this accounting result would manifest as reduced consumption or investment, which, in turn, would reduce overall aggregate demand.

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms lay-off workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession.

So the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur. Given the question assumes on-going external deficits, the implication is that the exogenous intervention would come from an expanding public deficit. Clearly, if the external sector improved the expansion could come from net exports.

It is possible that at the same time that the households and firms are reducing their consumption in an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

So it is possible that the public budget balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving ratio if net exports were strong enough.

The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors.

So given that the budget deficit has to be larger than the external deficit, the best answer is maybe.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: