If a nation is enjoying an external deficit, then one other sector must be spending more than it is earning.

Answer: True

The answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances - the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance - that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent - given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I - S) + (X - M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

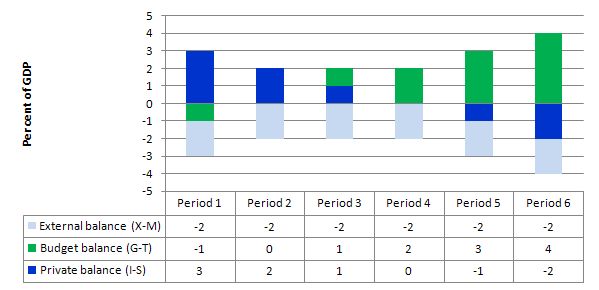

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP (which is artificial because as economic activity changes imports also rise and fall).

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If we assume these Periods are average positions over the course of each business cycle (that is, Period 1 is a separate business cycle to Period 2 etc).

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), a budget surplus of 1 per cent of GDP and the private sector is in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

In Period 2, as the government budget enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit. This is the case that the question is referring to.

This provides another important rule with the deficit terrorists typically overlook - that if a nation records an average external deficit over the course of the business cycle (peak to peak) and you succeed in balancing the public budget then the private domestic sector will be in deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt to fund its "excess expenditure". That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a budget with an external deficit. It could never be a viable fiscal rule.

With an external deficit, it is impossible for both the government and the private domestic sector to reduce their overall debt levels by spending less than they earn.

In Periods 3 and 4, the budget deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of budget deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

So what is the economics that underpin these different situations?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative - that is net drain of spending - dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is "earning" and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

So if the G is spending less than it is "earning" and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government budget deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Question 5 - Premium question:

It is clear that the central bank can use balance sheet management techniques to control yields on public debt at certain targetted maturities. However, this capacity to control the term structure of interest rates is diminished during periods of high inflation.

The answer is True.

I was going to use the term "economic impact" but decided against that because it might be misleading given that it would require a discussion of what an economic impact actually is. I consider an economic impact has to involve a discussion of the real economy rather than just the financial dimensions.

In that context you would then have had to consider two things: (a) the impact on private interest rates; and (b) whether interest rates matter for aggregate demand. And in a simple dichotomous choice (true/false) that becomes somewhat problematic.

I chose the alternative "impact on the term structure" because it didn't require any consideration of the real economy but only the impact on private interest rates.

The "term structure" of interest rates, in general, refers to the relationship between fixed-income securities (public and private) of different maturities. Sometimes commentators will confine the concept to public bonds but that would be apparent from the context. Usually, the term structure takes into account public and private bonds/paper.

The yield curve is a graphical depiction of the term structure - so that the interest rates on bonds are graphed against their maturities (or terms).

The term structure of interest rates provides financial markets with a indication of likely movements in interest rates and expectations of the state of the economy.

If the term structure is normal such that short-term rates are lower than long-term rates fixed-income investors form the view that economic growth will be normal. Given this is associated with an expectation of some stable inflation over the medium- to longer-term, long maturity assets have higher yields to compensate for the risk.

Short-term assets are less prone to inflation risk because holders are repaid sooner.

When the term structure starts to flatten, fixed-income markets consider this to be a transition phase with short-term rates on the rise and long-term rates falling or stable. This usually occurs late in a growth cycle and accompanies the tightening of monetary policy as the central bank seeks to reduce inflationary expectations.

Finally, if a flat terms structure inverts, the short-rates are higher than the long-rates. This results after a period of central bank tightening which leads the financial markets to form the view that interest rates will decline in the future with longer-term yields being lower. When interest rates decrease, bond prices rise and yields fall.

The investment mentality is tricky in these situations because even though yields on long-term bonds are expected to fall investors will still purchase assets at those maturities because they anticipate a major slowdown (following the central bank tightening) and so want to get what yields they can in an environment of overall declining yields and sluggish economic growth.

So the term structure is conditioned in part by the inflationary expectations that are held in the private sector.

It is without doubt that the central bank can manipulate the yield curve at all maturities to determine yields on public bonds. If they want to guarantee a particular yield on say a 30-year government bond then all they have to do is stand ready to purchase (or sell) the volume that is required to stabilise the price of the bond consistent with that yield.

Remember bond prices and yields are inverse. A person who buys a fixed-income bond for $100 with a coupon (return) of 10 per cent will expect $10 per year while they hold the bond. If demand rises for this bond in secondary markets and pushes the price up to say $120, then the fixed coupon (10 per cent on $100 = $10) delivers a lower yield.

Now it is possible that a strategy to fix yields on public bonds at all maturities would require the central bank to own all the debt (or most of it). This would occur if the targeted yields were not consistent with the private market expectations about future values of the short-term interest rate.

If the private markets considered that the central bank would stark hiking rates then they would decline to buy at the fixed (controlled) yield because they would expect long-term bond prices to fall overall and yields to rise.

So given the current monetary policy emphasis on controlling inflation, in a period of high inflation, private markets would hold the view that the yields on fixed income assets would rise and so the central bank would have to purchase all the issue to hit its targeted yield.

In this case, while the central bank could via large-scale purchases control the yield on the particular asset, it is likely that the yield on that asset would become dislocated from the term structure (if they were only controlling one maturity) and private rates or private rates (if they were controlling all public bond yields).

So the private and public interest rate structure could become separated. While some would say this would mean that the central bank loses the ability to influence private spending via monetary policy changes, the reality is that the economic consequences of such a situation would be unclear and depend on other factors such as expectations of future movements in aggregate demand, to name one important influence.