Given the existence of a few nations that run large external surpluses, most nations run current account deficits. Under these conditions, the deficit nations operate within the constraint that national income movements will ensure that the two remaining sectors (government and private domestic) end up spending more than they receive, irrespective of the GDP growth rate.

Answer: False

The answer is False.

The sectoral balances framework tells us that when the external sector is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. At least one of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

National income movements will always deliver that outcome and the balances that each sector records will be determined by a combination of their own spending decisions and the spillovers from the other sectors that impact on their respective incomes.

It also follows that it doesn't matter how fast GDP is growing.

The national accounts concept underpin the basic income-expenditure model that is at the heart of introductory macroeconomics. We can view this model in two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

So from the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

So if we equate these two perspectives of GDP, we get:

C + S + T = C + I + G + (X - M)

This can be simplified by cancelling out the C from both sides and re-arranging (shifting things around but still satisfying the rules of algebra) into what we call the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

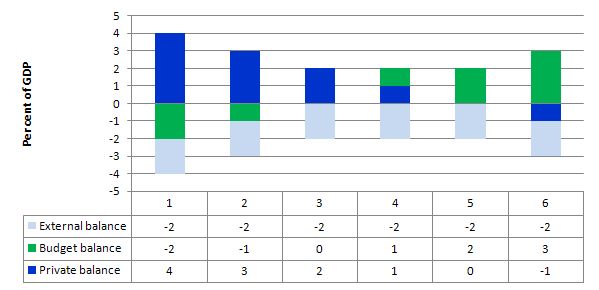

Consider the following graph and associated table of data which shows six states. All states have a constant external deficit equal to 2 per cent of GDP (light-blue columns).

State 1 show a government running a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP (green columns). As a consequence, the private domestic balance is in deficit of 4 per cent of GDP (royal-blue columns).

State 2 shows that when the budget surplus moderates to 1 per cent of GDP the private domestic deficit is reduced. State 3 is a budget balance and then the private domestic deficit is exactly equal to the external deficit. So the private sector spending more than they earn exactly funds the desire of the external sector to accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue in this country.

States 4 to 6 shows what happens when the budget goes into deficit - the private domestic sector (given the external deficit) can then start reducing its deficit and by State 5 it is in balance. Then by State 6 the private domestic sector is able to net save overall (that is, spend less than its income) because the budget deficit (adding demand) is greater than the external deficit (draining demand).

Note also that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts.

Most countries currently run external deficits. The crisis was marked by households reducing consumption spending growth to try to manage their debt exposure and private investment retreating. The consequence was a major spending gap which pushed budgets into deficits via the automatic stabilisers.

The only way to get income growth going in this context and to allow the private sector surpluses to build was to increase the deficits beyond the impact of the automatic stabilisers. The reality is that this policy change hasn't delivered large enough budget deficits (even with external deficits narrowing). The result has been large negative income adjustments which brought the sectoral balances into equality at significantly lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: