The EU/IMF/ECB strategy for Greece is twofold: (a) cutting real wages to improve external competitiveness; and (b) pushing the government back into surplus. The aim is to reduce the budget deficit without compromising real economic growth. It is hoped that an increase in net exports will replace the loss of spending from fiscal austerity. Suppose that the government announced it intended to cut its deficit from 4 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent in the coming year and during that year net exports were projected to move from a deficit of 1 per cent of GDP to a surplus of 1 per cent of GDP. In that situation we would conclude that the fiscal austerity plans would not undermine growth if the net export projection was realised.

Answer: False

The answer is False.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

From an accounting sense, if the external sector goes into surplus (positive net exports) there is scope for the government balance to move into surplus without compromising growth as long as the external position more than offsets any actual private domestic sector net saving.

In that sense, the EU/IMF/ECB strategy requires more than net exports adding as much aggregate demand as the government destroys with its fiscal austerity.

Skip the next section explaining the balances if you are familiar with the derivation. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced.

Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I - S) + (X - M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

If the nation is running an external surplus it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is positive - that is net spending injection - providing a boost to domestic production and income generation.

The extent to which this allows the government to reduce its deficit (by the same amount as the run a surplus equal to the external balance and not endanger growth depends on the private domestic sector's spending decisions (overall). If the private domestic sector runs a deficit, then the EU/IMF/ECB strategy will work under the assumed conditions - inasmuch as the goal is to reduce the budget deficit without compromising growth.

But this strategy would be unsustainable as it would require the private domestic sector overall to continually increase its indebtedness.

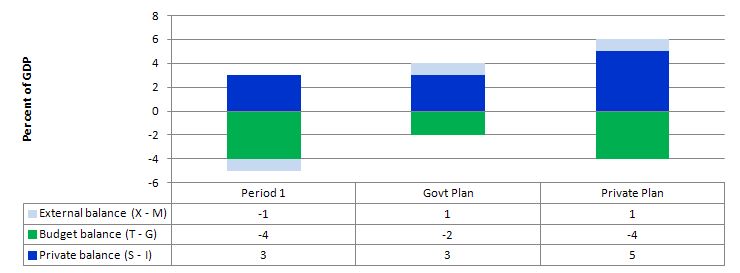

The following graph captures what might happen if the private domestic sector (households and firms) seeks to increase its overall saving at the same time the net exports are rising and the government deficit is falling.

In Period 1, there is an external deficit of 1 per cent of GDP and a budget deficit of 4 per cent of GDP which generates income sufficient to allow the private domestic sector.

The Government plans to cut its deficit to 2 per cent of GDP by cutting spending. To achieve that with net exports rising to 1 per cent of GDP and for there to be no change in aggregate demand then the private domestic sector is assumed not to be changing its saving behaviour.

However, what happens if the private sector, fearing the contractionary forces coming from the announced cuts in public spending and not really being in a position to assess what might happen to net exports over the coming period, decides to increase its saving. In other words, they plan to increase net saving to 5 per cent of GDP - the situation captured under the Private Plan option.

In this case, if the private sector actually succeeded in reducing its spending and increasing its saving balance to 5 per cent of GDP, the income shifts would ensure the government could not realise its planned deficit reduction.

The public and private plans are clearly not compatible and the resolution of their competing objectives would be achieved by income shifts.

In other words, as the private sector and the public sector reduced their spending in pursuit of their plans, income would contract even though net exports were rising.

The situation is that unless private sector behaviour remains constant the government cannot rely on an increase in net exports to provide the space for them to cut their own net spending.

So in general, with the government contracting the only way the private domestic sector could successfully increase its net saving is if the injection from the external sector offsett the drain from the domestic sector (public and private). Otherwise, income will decline and both the government and private domestic sector will find it difficult to reduce their net spending positions.

Take a balanced budget position, then income will decline unless the private domestic sector's saving overall is just equal to the external surplus. If the private domestic sector tried to push its position further into surplus then the following story might unfold.

Consistent with this aspiration, households may cut back on consumption spending and save more out of disposable income. The immediate impact is that aggregate demand will fall and inventories will start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms will soon react to the increased inventory holding costs and will start to cut back production. How quickly this happens depends on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But if the households persist in trying to save more and consumption continues to lag, then soon enough the economy starts to contract - output, employment and income all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption multiplies through the expenditure system as workers who are laid off also lose income and their spending declines. This leads to further contractions.

The declining income leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

So the initial discretionary decline in consumption is supplemented by the induced consumption falls driven by the multiplier process.

The decline in income then stifles firms' investment plans - they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further towards and eventually into surplus

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which push the public budget balance towards and eventually into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

If the private sector persists in trying to increase its saving ratio then the contracting income will clearly push the budget into deficit.

So the external position has to be sufficiently strong enough to offset the domestic drains on expenditure. For Greece at present that is clearly not the case and demonstrates why the EU/ECB/IMF strategy is failing.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: