If private domestic investment is less than private domestic saving and the current account is draining aggregate demand then the government budget has to be in deficit no matter what level of GDP is produced.

Answer: True

The answer is True.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

Refreshing the balances (again) - we know that from an accounting sense, if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

The important point is to understand what behaviour and economic adjustments drive these outcomes.

So here is the accounting (again). The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I - S) + (X - M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

So what about the situation posed in the question?

If the external sector is draining aggregate demand it must mean the current account is in deficit. That is , spending flows out of the local economy are greater than spending flows coming into the economy from the foreign sector.

If private domestic investment is less than private domestic saving, then the private domestic sector is running a surplus overall - that is, they are spending less than they are earning.

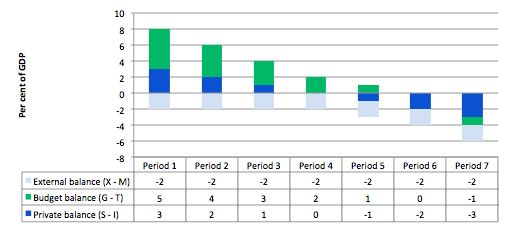

The following graph shows the sectoral balances for seven periods based on different levels of the private balance (as a per cent of GDP) and a constant external deficit (to keep things simple).

You can see that in Periods 1 to 3, the private sector is in surplus while the external sector is in deficit. The budget (G - T) is in deficit in each of those periods. The budget only goes into surplus (with a 2 per cent of GDP external deficit) when the injection into aggregate demand from the private domestic sector is greater than the spending drain from the external sector (Period 7).

The reasoning is as follows. If the private domestic sector (households and firms) is saving overall it means that some of the income being produced is not be re-spent. So the private domestic surplus represents a drain on aggregate demand. The external sector is also leaking expenditure. At the current GDP level, if the government didn't fill the spending gap resulting from the other sectors, then inventories would start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms would react to the increased inventory holding costs and would cut back production. How quickly this downturn occurs would depend on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But the result would be that the economy would contract - output, employment and income would all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption would multiply through the expenditure system as laid-off workers lose income and cut back on their spending. This would lead to further contractions.

Declining national income (GDP) leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

The decline in income then stifles firms' investment plans - they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further into surplus

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which push the public budget balance towards and eventually into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

So with an external deficit and a private domestic surplus there will always be a budget deficit.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: