In a nation running an on-going external deficit, if the private domestic sector decides to increase the extent that it spends less than its overall income, then the national government has to increase its discretionary fiscal deficit in order to avoid rising employment losses.

Answer: True

The answer is True.

First, we must understand the linkages between the external and domestic situation.

To refresh your memory the sectoral balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all taxes and transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X - M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total taxes and transfers (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP - T = C + I + G + (X - M) + FNI - T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP - C - T) - I = (G - T) + (X - M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP - C - T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP - C - T) - I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP - C - T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G - T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X - M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S - I) = (G - T) + CAB

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G - T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAB > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G - T < 0) and current account deficits (CAB < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S - I) - CAB] = (G - T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S - I) - CAB] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

(S - I) denotes the relationship between private domestic income and spending. If S > I then, the private domestic sector is saving overall, which is different to saying the household sector is saving out of its disposable income.

When the private domestic sector seeks to increase the gap between S and I, they will reduce consumption or investment spending, which, in turn, directly reduces overall aggregate spending.

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this.

Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly.

They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms lay-off workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession.

There are only two ways out of this in order to avoid spiralling employment losses and both require an exogenous intervention to occur.

1. The fiscal deficit has to rise.

2. Net exports have to rise.

But we need to understand that at some steady state position (where changes in national income are zero), a change in one of the balances will force, via the resulting income changes, changes in the other two balances.

The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors.

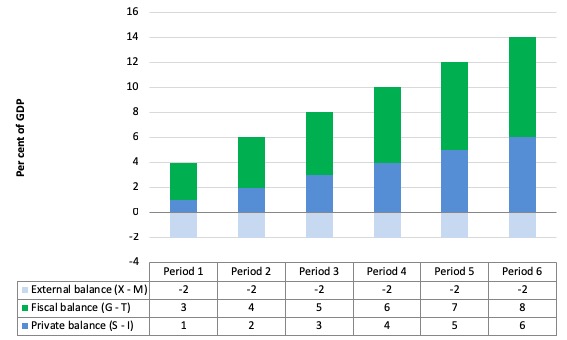

Consider the following graph, which shows a constant (on-going) external deficit of 2 per cent of GDP.

For the private domestic sector to save overall, the fiscal position has to be in deficit when there is an external deficit, irrespective of the size of the external deficit.

As we move from Period 1 to Period 6, the private domestic sector is achieving even greater overall saving and the fiscal deficit is rising as a consequence.

The fiscal deficit will rise without the government acting because of the automatic stabilisers - the slowdown in the economy from the withdrawal of private domestic spending will reduce tax revenue and increase welfare payments.

But that will typically not be sufficient to avoid employment losses.

So the government has to increase its discretionary net spending to ensure there is sufficient aggregate spending growth to keep pace with the rising private domestic sector spending withdrawal.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: