The private domestic sector will save overall even if the government's fiscal balance is in surplus as long as net exports are positive.

Answer: False

The answer is False.

Focus on the "will" part of the question.

This is a question about the sectoral balances - the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance - that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent - given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

So what economic behaviour might lead to the outcome specified in the question?

If the nation is running an external surplus it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is positive - that is adding to spending on domestically produced goods and services.

So if the fiscal outcome was in balance - neither adding or subtracting from aggregate demand, the external surplus would provide sufficient demand for the private domestic sector to save overall equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP.

Assume, now that the private domestic sector (households and firms) desires to save overall more than 1 per cent of GDP. Consistent with this aspiration, households may cut back on consumption spending and save more out of disposable income. The immediate impact is that aggregate demand will fall and inventories will start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms will soon react to the increased inventory holding costs and will start to cut back production. How quickly this happens depends on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But if the households persist in trying to save more and consumption continues to lag, then soon enough the economy starts to contract - output, employment and income all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption multiplies through the expenditure system as workers who are laid off also lose income and their spending declines. This leads to further contractions.

The declining income leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

So the initial discretionary decline in consumption is supplemented by the induced consumption falls driven by the multiplier process.

The decline in income then stifles firms' investment plans - they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further towards and eventually into surplus.

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which would in this instance push the public fiscal balance into deficit via the automatic stabilisers if there were no discretionary policy changes made by government.

If the private sector persists in trying to increase its overall saving then the contracting income will clearly push the fiscal balance into a larger deficit.

So if there is an external surplus and the private domestic sector saves overall (a surplus) then the fiscal surplus has to be lower than the external surplus.

If the government tried to run a surplus greater than the external surplus then then the net drain on aggregate demand would reduce national income and saving for given investment levels and drive the private domestic sector into deficit.

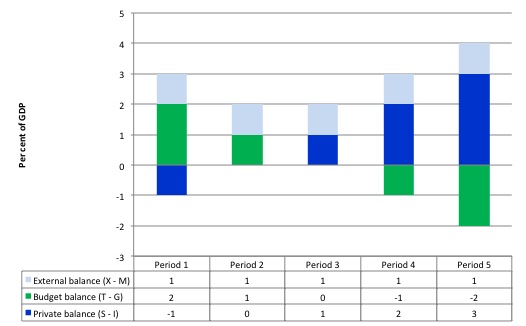

The following graph and related data table shows you how a fiscal surplus equivalent to the external surplus will not permit the private domestic sector to save overall.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: