If there is an external deficit of 2 per cent of GDP and the government achieves a fiscal balance then the private domestic sector will have

Answer: an excess of spending relative to its income equal to 2 per cent of GDP.

The correct answer is Option (a) - "an excess of spending relative to its income overall equal to 2 per cent of GDP".

This is a question about the sectoral balances - the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance - that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent - given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I - S) + (X - M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

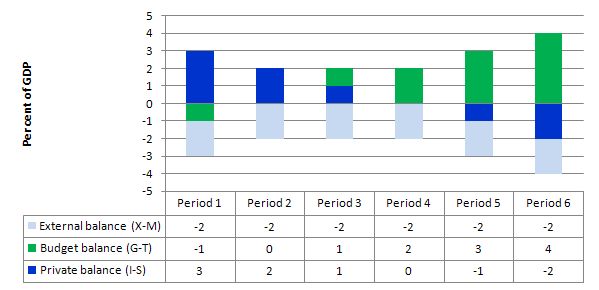

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP.

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If we assume these Periods are average positions over the course of each business cycle (that is, Period 1 is a separate business cycle to Period 2 etc).

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), a fiscal surplus of 1 per cent of GDP and the private sector is in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

In Period 2, as the government fiscal balance enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit. This is the case that the question is referring to.

So this is the situation described in the Question which means that the private sector is running an overall deficit - so incurring an "excess of spending over its income overall equal to 2 per cent of GDP".

This provides another important rule with the deficit terorists typically overlook - that if a nation records an average external deficit over the course of the business cycle (peak to peak) and you succeed in balancing the public fiscal balance then the private domestic sector will be in deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt to fund its "excess expenditure". That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a fiscal balance with an external deficit. It could never be a viable fiscal rule.

In Periods 3 and 4, the fiscal deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of fiscal deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

So what is the economics that underpin these different situations?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative - that is net drain of spending - dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is "earning" and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

So if the G is spending less than it is "earning" and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government fiscal deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: