A national government which runs a balanced budget over the economic cycle (peak to peak) will ensure that households and firms overall spend more than they earn - that is, run down previous savings or accumulate more net debt, once all the national spending and income adjustments are exhausted.

Answer: False

The answer is False.

Note that this question begs the question as to how the economy might get into this situation that I have described. But whatever behavioural forces were at play, the sectoral balances all have to sum to zero. Once you understand that, then deduction leads to the correct answer.

The trick in the question is that the households and firms overall do not exhaust the non-government sector. So what happens when the governments runs a balanced budget to the private domestic sector balance (the households and firms) depends crucially on what happens to the external sector.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X - M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I - S) + (G - T) + (X - M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn't alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I - S) + (X - M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

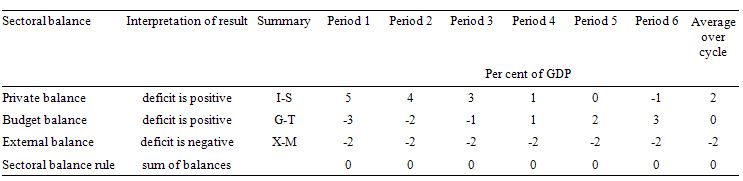

To help us answer the specific question posed, the following Table shows a stylised business cycle with some simplifications. The economy is running a budget surplus in the first three periods (but declining) and then increasing budget deficits. Over the entire cycle the balanced budget rule would be achieved as the budget balances average to zero. So the deficits are covered by fully offsetting surpluses over the cycle.

The simplification is the constant external deficit (that is, no cyclical sensitivity) of 2 per cent of GDP over the entire cycle. You can then see what the private domestic balance is doing clearly. When the budget balance is in surplus, the private balance is in deficit. The larger the budget surplus the larger the private deficit for a given external deficit.

As the budget moves into deficit, the private domestic balance approaches balance and then finally in Period 6, the budget deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) and so the private domestic sector can save overall. The budget deficits are underpinning spending and allowing income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector.

On average over the cycle, under these conditions (balanced public budget) the private domestic deficit exactly equals the external deficit. As a result over the course of the business cycle, the private domestic sector becomes increasingly indebted.

But if the external sector was in surplus, on average, over the economic cycle the conclusion would be different. What situations might arise then?

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: