If policy makers use NAIRU estimates to compute the decomposition between structural and cyclical fiscal balances and these estimates are above the true full employment unemployment rate, then the estimated impact of the automatic stabilisers will always be biased downwards.

Answer: True

The answer is True.

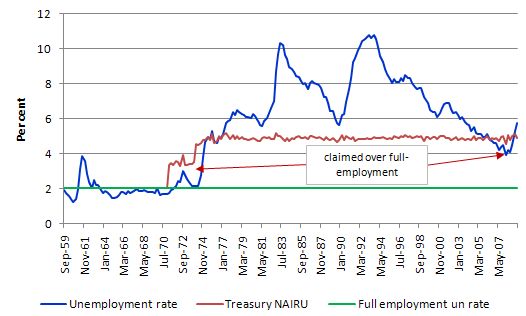

The following graph plots the actual unemployment rate for Australia (blue line) from 1959 to June 2009 and the Australian Treasury estimate of the NAIRU (red line). The data is available from the RBA.

You can see how ridiculous the estimated NAIRU is. Suddenly it jumps up just as actual unemployment rises although for such a jump to occur (according to the logic of the concept) there has to be major structural changes occurring. Historically, there is nothing that might convincingly explain that jump. Other estimation techniques give even more nonsensical estimates (they tend to just track the movement in the official unemployment rate).

This graph show how little correspondence there is between the inflation rate and the NAIRU gap (measured as the difference between the estimated NAIRU and the actual unemployment rate). The left-panel is the actual inflation rate (vertical axis) whereas the right-panel is the change in the actual inflation rate (vertical axis). There has always been some dispute in the literature as to whether the Phillips curve (the relationship between the NAIRU gap and inflation) should be specified in terms of the actual level of inflation or the acceleration in the level.

I also tried various lags in the inflation measures (to allow for frictions) and you get the same general picture. If the mainstream economic theory was correct, then the NAIRU gap should be negatively related to inflation (whichever measure you like). That is, when the unemployment rate is above the NAIRU inflation should be falling and vice versa. The conclusion from the data is that no such relationship exists. There is no surprise in that - the NAIRU is one of the most discredited concepts in the mainstream toolkit. The problem is that governments have been significantly influenced by it to the detriment of all of us.

To see why this is the case, the next graph plots three different measures of labour market tightness:

The NAIRU estimates not only inflate the alleged full employment unemployment rate but also completely ignore the underemployment, which has risen sharply over the last 20 years.

For example, in the June-quarter 2006 the NAIRU gap was zero whereas the actual unemployment rate was still 2.78 per cent above the full employment unemployment rate. The thick red vertical line depicts this distance.

However, if we considered the labour market slack in terms of the broad labour underutilisation rate published by the ABS then the gap would be considerably larger. Thus you have to sum the red and green vertical lines shown at June 2008 for illustrative purposes.

This means that the Australian Treasury are providing advice to the Federal government claiming that in June 2008 the Australian economy was at full employment when it is highly likely that there was upwards of 9 per cent of willing labour resources being wasted. That is how bad the NAIRU period has been for policy advice.

But in relation to this question, in June 2008, the Australian Treasury would have classified all of the federal fiscal balance in that quarter as being structural given that the cycle was considered to be at the peak (what they term full employment).

However, if we define the true full employment level was at 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment, then you can see that, in fact, the Australian economy would have been operating well below the full employment level and so there would have been a significant cyclical component being reflected in the fiscal balance.

Given the federal fiscal balance in June 2008 was in surplus the Treasury would have classified this as mildly contractionary whereas in fact the Commonwealth government was running a highly contractionary fiscal position which was preventing the economy from generating a greater number of jobs.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you: