The reason that IMF and OECD estimates of structural fiscal deficits are to be treated with suspicion relates to the fact that typically the implicit estimates of potential GDP are too optimistic.

Answer: False

The answer is False.

The correct statement is the implicit estimates of potential GDP that are produced by central banks, treasuries and other bodies are too pessimistic.

The reason is that they typically use the NAIRU to compute the "full capacity" or potential level of output which is then used as a benchmark to compare actual output against. The reason? To determine whether there is a positive output gap (actual output below potential output) or a negative output gap (actual output above potential output).

These measurements are then used to decompose the actual fiscal outcome at any point in time into structural and cyclical fiscal balances. The fiscal components are adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the fiscal balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the fiscal outcome is in deficit when computed at the "full employment" or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the fiscal outcome into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The difference between the actual fiscal outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical fiscal outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

As you can see, the estimation of the benchmark is thus a crucial component in the decomposition of the fiscal outcome and the interpretation we place on the fiscal policy stance.

If the benchmark (potential output) is estimated to be below what it truly is, then a sluggish economy will be closer to potential than if you used the true full employment level of output. Under these circumstances, one would conclude that the fiscal stance was more expansionary than it truly was.

This is very important because the political pressures may then lead to discretionary cut backs to "reign in the structural deficit" even though it is highly possible that at that point in time, the structural component is actually in surplus and therefore constraining growth.

The mainstream methodology involved in estimating potential output almost always uses some notion of a NAIRU which itself is unobserved. The NAIRU estimates produced by various agencies (OECD, IMF etc) always inflate the true full employment unemployment rate and completely ignore underemployment, which has risen sharply over the last 20 years.

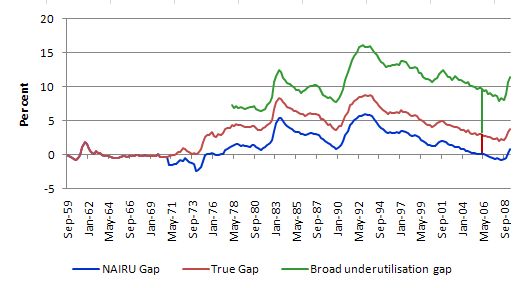

The following graph is for Australia but it broadly representative of the types of constructs we are dealing with. It plots three different measures of labour market tightness:

Some might ask why would we assume that 2 per cent unemployment rate is a true full employment level? We know that unemployment will always be non-zero because of frictions - people leaving jobs and reconnecting with other employers. This component is somewhere around 2 per cent. The other components of unemployment which economists define are seasonal, structural and demand-deficient. Seasonal unemployment is tied up with frictional and likely to be small.

The concept of structural unemployment is vexed. I actually don't think it exists because ultimately comes down to demand-deficient. The concept is biased towards a view that only private market employment are real jobs and so if the market doesn't want a particular skill group or does not choose to provide work in a particular geographic area then the mis-match unemployment is structural.

The problem is that often there are unemployed workers in areas where employers claim there are skills shortages. The firms will not employ these workers and offer them training opportunities within the paid work environment because they exercise discrimination. So what is actually considered structural is just a reflection of employer prejudice and an unwillingness to extend training opportunities to some cohorts of workers.

Also, the government can always generate enough demand to provide jobs to all in every area should it choose. So ultimately, any unemployment that looks like it is "structural" is in fact due to a lack of demand.

So there is no reason why any economy cannot get their unemployment rate down to 2 per cent.

Given that, the NAIRU estimates not only inflate the true full employment unemployment rate but also completely ignore the underemployment, which has risen sharply over the last 20 years.

In the June quarter 2006 the Australian NAIRU gap was zero whereas the actual unemployment rate was still 2.78 per cent above the full employment unemployment rate. The thick red vertical line depicts this distance.

However, if we considered the labour market slack in terms of the broad labour underutilisation rate published by the ABS then the gap would be considerably larger - a staggering 9.4 per cent. Thus you have to sum the red and green vertical lines shown at June 2008 for illustrative purposes.

This means that the Australian Treasury are providing advice to the Federal government claiming that in June 2008 the Australian economy was at full employment when it is highly likely that there was upwards of 9 per cent of willing labour resources being wasted. That is how bad the NAIRU period has been for policy advice.

But in relation to this question, in June 2008, the Australian Treasury would have classified all of the federal fiscal balance in that quarter as being structural given that the cycle was considered to be at the peak (what they term full employment).

However, if we define the true full employment level was at 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment, then you can see that, in fact, the Australian economy would have been operating well below the full employment level and so there would have been a significant cyclical component being reflected in the fiscal balance.

Given the federal fiscal outcome in June 2008 was in surplus the Treasury would have classified this as mildly contractionary whereas in fact the Commonwealth government was running a highly contractionary fiscal position which was preventing the economy from generating a greater number of jobs.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: