Assume the current public debt to GDP ratio is 100 per cent and that the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate remain constant and zero. Under these circumstances it is impossible to reduce a public debt to GDP ratio, using an austerity package if the rise in the primary fiscal surplus to GDP ratio is always exactly offset by negative GDP growth rate of the same percentage value.

Answer: True

The answer is True.

This question plays on the first but investigates a difference aspect of the framework outlined above.

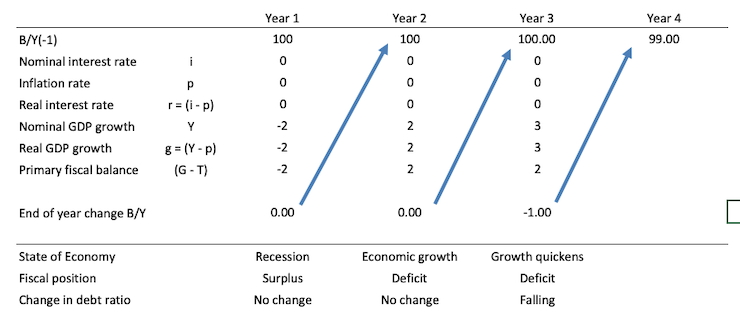

The following Table considers a three-year horizon.

At the beginning of Year 1, the nation inherits a public debt ratio of 100 per cent.

The economy is in recession (g = minus 2 per cent) and the real interest rate (r) is zero (because it equals the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate).

Under pressure from conservative lobby groups to reduce the fiscal deficit the nation carried over from the previous year, and, also reduce the public debt ratio, the government introduces a fiscal austerity program (with harsh public spending cuts) during Year 1.

The government succeeds in running a primary fiscal surplus of 2 per cent of GDP (note: the fiscal balance, G-T is negative when in surplus) and the economy remains in recession

As a result, by the end of Year 1, the public debt ratio is unchanged but the economy remains in recession.

The general rule is that under these conditions (r = 0), there can be no reduction in the public debt ratio as long as the primary fiscal surplus as a per cent of GDP is exactly equal to the negative GDP growth rate.

The austerity dynamic, however, is likely to push the public debt ratio up.

Why?

First, if the government didn't change its strategy and held to its austerity program, then it will probably push the GDP growth rate further into negative territory, which, other things equal, would push the public debt ratio up.

Second, as GDP growth declines further, the automatic stabilisers will push the fiscal balance result towards (and into after a time) deficit, which, given the borrowing rules that governments volunatarily enforce on themselves, would also push the public debt ratio up.

So austerity packages, quite apart from their highly destructive impacts on real standards of living and social standards, typically fail to reduce public debt ratios and usually increase them.

But, our government here is responsible and in Year 2, intent of combatting the recession, the government decides to ignore the public debt obsession and introduces a fiscal stimulus (primary fiscal deficit increases to 2 per cent of GDP).

The economy responds to the fiscal stimulus with a 2 per cent growth rate and exits recession.

Again, the public debt ratio is unchanged.

This is because the fiscal deficit is exactly offset (in percentage terms) by the growth rate.

To further mop up unemployment and slack areas in the economy, the government holds its primary fiscal deficit stimulus at 2 per cent of GDP and the economy's growth rate improves further to 3 per cent in Year 3.

So by year's end, the debt ratio has fallen (by 1 per cent).

An economy that is experiencing growth with fiscal stimulus support will typically see its public debt ratio falling. And, the fiscal balance declines because of the higher economic activity.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.