Historically, government debt has been used by central banks to manage liquidity and sustain positive short-term policy interest rates targets. This function necessitates that currency-issuing governments continue to, at least, issue enough debt to allow these open market operations to continue.

Answer: False

The answer is False.

The question is specifically about the dynamics of bank reserves which are used to satisfy any imposed reserve requirements and facilitate the payments system. These dynamics have a direct bearing on monetary policy settings. Given that the dynamics of the reserves can undermine the desired monetary policy stance (as summarised by the policy interest rate setting), the central banks have to engage in liquidity management operations.

What are these liquidity management operations?

Well you first need to appreciate what reserve balances are.

The New York Federal Reserve Bank's paper - Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy said that:

... reserve balances are used to make interbank payments; thus, they serve as the final form of settlement for a vast array of transactions. The quantity of reserves needed for payment purposes typically far exceeds the quantity consistent with the central bank's desired interest rate. As a result, central banks must perform a balancing act, drastically increasing the supply of reserves during the day for payment purposes through the provision of daylight reserves (also called daylight credit) and then shrinking the supply back at the end of the day to be consistent with the desired market interest rate.

So the central bank must ensure that all private cheques (that are funded) clear and other interbank transactions occur smoothly as part of its role of maintaining financial stability. But, equally, it must also maintain the bank reserves in aggregate at a level that is consistent with its target policy setting given the relationship between the two.

So operating factors link the level of reserves to the monetary policy setting under certain circumstances. These circumstances require that the return on "excess" reserves held by the banks is below the monetary policy target rate. In addition to setting a lending rate (discount rate), the central bank also sets a support rate which is paid on commercial bank reserves held by the central bank.

Many countries (such as Australia and Canada) maintain a default return on surplus reserve accounts (for example, the Reserve Bank of Australia pays a default return equal to 25 basis points less than the overnight rate on surplus Exchange Settlement accounts). Other countries like the US and Japan have historically offered a zero return on reserves which means persistent excess liquidity would drive the short-term interest rate to zero.

The support rate effectively becomes the interest-rate floor for the economy. If the short-run or operational target interest rate, which represents the current monetary policy stance, is set by the central bank between the discount and support rate. This effectively creates a corridor or a spread within which the short-term interest rates can fluctuate with liquidity variability. It is this spread that the central bank manages in its daily operations.

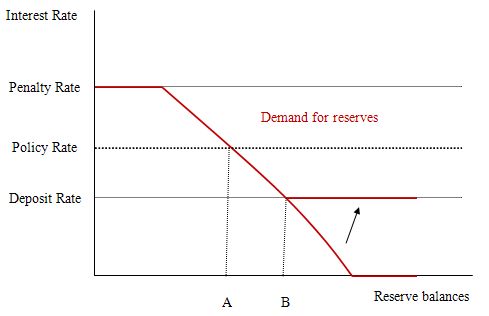

So the issue then becomes - at what level should the support rate be set? To answer that question, I reproduce a version of teh diagram from the FRBNY paper which outlined a simple model of the way in which reserves are manipulated by the central bank as part of its liquidity management operations designed to implement a specific monetary policy target (policy interest rate setting).

I describe the FRBNY model in detail in the blog - Understanding central bank operations so I won't repeat that explanation.

The penalty rate is the rate the central bank charges for loans to banks to cover shortages of reserves. If the interbank rate is at the penalty rate then the banks will be indifferent as to where they access reserves from so the demand curve is horizontal (shown in red).

Once the price of reserves falls below the penalty rate, banks will then demand reserves according to their requirments (the legal and the perceived). The higher the market rate of interest, the higher is the opportunity cost of holding reserves and hence the lower will be the demand. As rates fall, the opportunity costs fall and the demand for reserves increases. But in all cases, banks will only seek to hold (in aggregate) the levels consistent with their requirements.

At low interest rates (say zero) banks will hold the legally-required reserves plus a buffer that ensures there is no risk of falling short during the operation of the payments system.

Commercial banks choose to hold reserves to ensure they can meet all their obligations with respect to the clearing house (payments) system. Because there is considerable uncertainty (for example, late-day payment flows after the interbank market has closed), a bank may find itself short of reserves. Depending on the circumstances, it may choose to keep a buffer stock of reserves just to meet these contingencies.

So central bank reserves are intrinsic to the payments system where a mass of interbank claims are resolved by manipulating the reserve balances that the banks hold at the central bank. This process has some expectational regularity on a day-to-day basis but stochastic (uncertain) demands for payments also occur which means that banks will hold surplus reserves to avoid paying any penalty arising from having reserve deficiencies at the end of the day (or accounting period).

To understand what is going on not that the diagram is representing the system-wide demand for bank reserves where the horizontal axis measures the total quantity of reserve balances held by banks while the vertical axis measures the market interest rate for overnight loans of these balances

In this diagram there are no required reserves (to simplify matters). We also initially, abstract from the deposit rate for the time being to understand what role it plays if we introduce it.

Without the deposit rate, the central bank has to ensure that it supplies enough reserves to meet demand while still maintaining its policy rate (the monetary policy setting.

So the model can demonstrate that the market rate of interest will be determined by the central bank supply of reserves. So the level of reserves supplied by the central bank supply brings the market rate of interest into line with the policy target rate.

At the supply level shown as Point A, the central bank can hit its monetary policy target rate of interest given the banks' demand for aggregate reserves. So the central bank announces its target rate then undertakes monetary operations (liquidity management operations) to set the supply of reserves to this target level.

So contrary to what mainstream textbooks tell students (that monetary policy is about controlling the money supply), the reality is that monetary policy is about changing the supply of reserves in such a way that the market rate is equal to the policy rate.

The central bank uses open market operations to manipulate the reserve level and so must be buying and selling government debt to add or drain reserves from the banking system in line with its policy target.

If there are excess reserves in the system and the central bank didn't intervene then the market rate would drop towards zero and the central bank would lose control over its target rate (that is, monetary policy would be compromised).

But, as explained in the blog - Understanding central bank operations - the introduction of a support rate payment (deposit rate) whereby the central bank pays the member banks a return on reserves held overnight changes things considerably.

It clearly can - under certain circumstances - eliminate the need for any open-market operations to manage the volume of bank reserves.

In terms of the diagram, the major impact of the deposit rate is to lift the rate at which the demand curve becomes horizontal (as depicted by the new horizontal red segment moving up via the arrow).

This policy change allows the banks to earn overnight interest on their excess reserve holdings and becomes the minimum market interest rate and defines the lower bound of the corridor within which the market rate can fluctuate without central bank intervention.

So in this diagram, the market interest rate is still set by the supply of reserves (given the demand for reserves) and so the central bank still has to manage reserves appropriately to ensure it can hit its policy target.

If there are excess reserves in the system in this case, and the central bank didn't intervene, then the market rate will drop to the support rate (at Point B).

So if the central bank wants to maintain control over its target rate it can either set a support rate below the desired policy rate (as in Australia) and then use open market operations to ensure the reserve supply is consistent with Point A or set the support (deposit) rate equal to the target policy rate.

The answer clearly presupposes that the central bank sets the support rate equal to the policy rate. In that situation, there will be no need for the central bank to manage liquidity via open market operations.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you: